There was a collective gasp when Dr. Katherine G. Lacson revealed that beauty pageants during the American colonial period in the Philippines were mired in lurid scandals, including ballot-buying. So they weren’t all glitz and glam, I learned while sitting through the breezy lecture at The Rockwell Club in August.

Lacson was the second speaker of “Cultural Intersections: The American Period,” a lecture series presented by the Lopez Museum and Library. For her “Ode to Pulchritude: Queens and Beauty Pageants during the American Period” lecture, she took a leaf from her PhD dissertation “Images in Print- The Manileña in periodicals (1898-1938)” that she completed at the Université Côte d’Azur in Nice, France. She used a combined theoretical framework of historical feminist perspective and Jurgen Habermas separate-spheres ideology to study the different types of representation of women in periodicals.

With “Ode to Pulchritude,” she reoriented the discussions on beauty pageants from commonplace opinions to critical perspectives.

Fairest of ’em all

Per Lacson, beauty, like love, is a perennial subject of creative masterpieces always synonymous to women. Historically, measuring beauty was done through the crowning of beauty queens at May Day and Spring festivals. But the concept of a “beauty contest” goes way back to “The Judgement of Paris,” a Greek myth about Paris of Troy judging the fairest among the goddesses Aphrodite, Athena, and Hera. (His choice of Athena, who promised him the most beautiful woman, Helen. launched the Trojan War.)

American showman-entertainer PT Barnum, famous for his carnival freak shows, popularized the format of presenting women before a panel of jurors.

“Beauty [became] a stage spectacle…with women being paraded before an audience to be judged,” Lacson, an associate professor at Ateneo de Manila University, said.

Manila wasn’t privy to the trend yet until the Americans exported it to the Philippines. However, beauty wasn’t impetus in introducing it, but a means to an end. Capt. George T. Langhorn was cash-strapped and, ironically, wasn’t allowed to use US funds to build the infrastructure in the Philippines, and so his solution was to raise funds from the colony through a beauty pageant, or the Manila Carnival.

Mardi Gras vibe

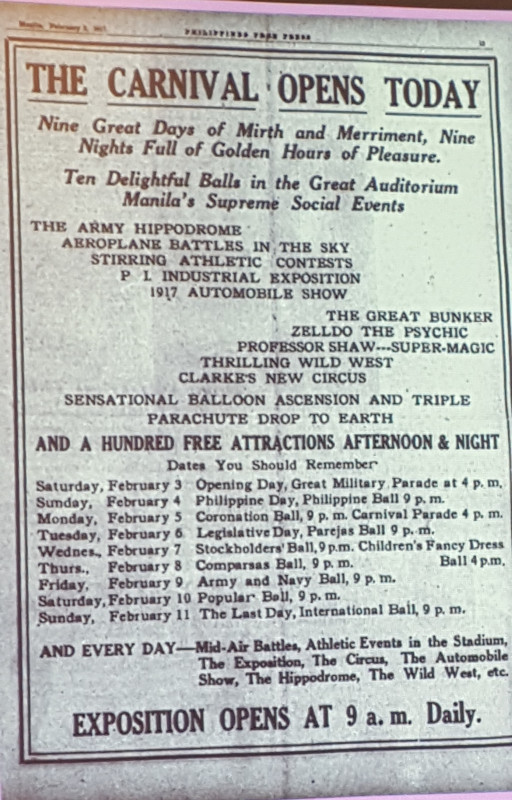

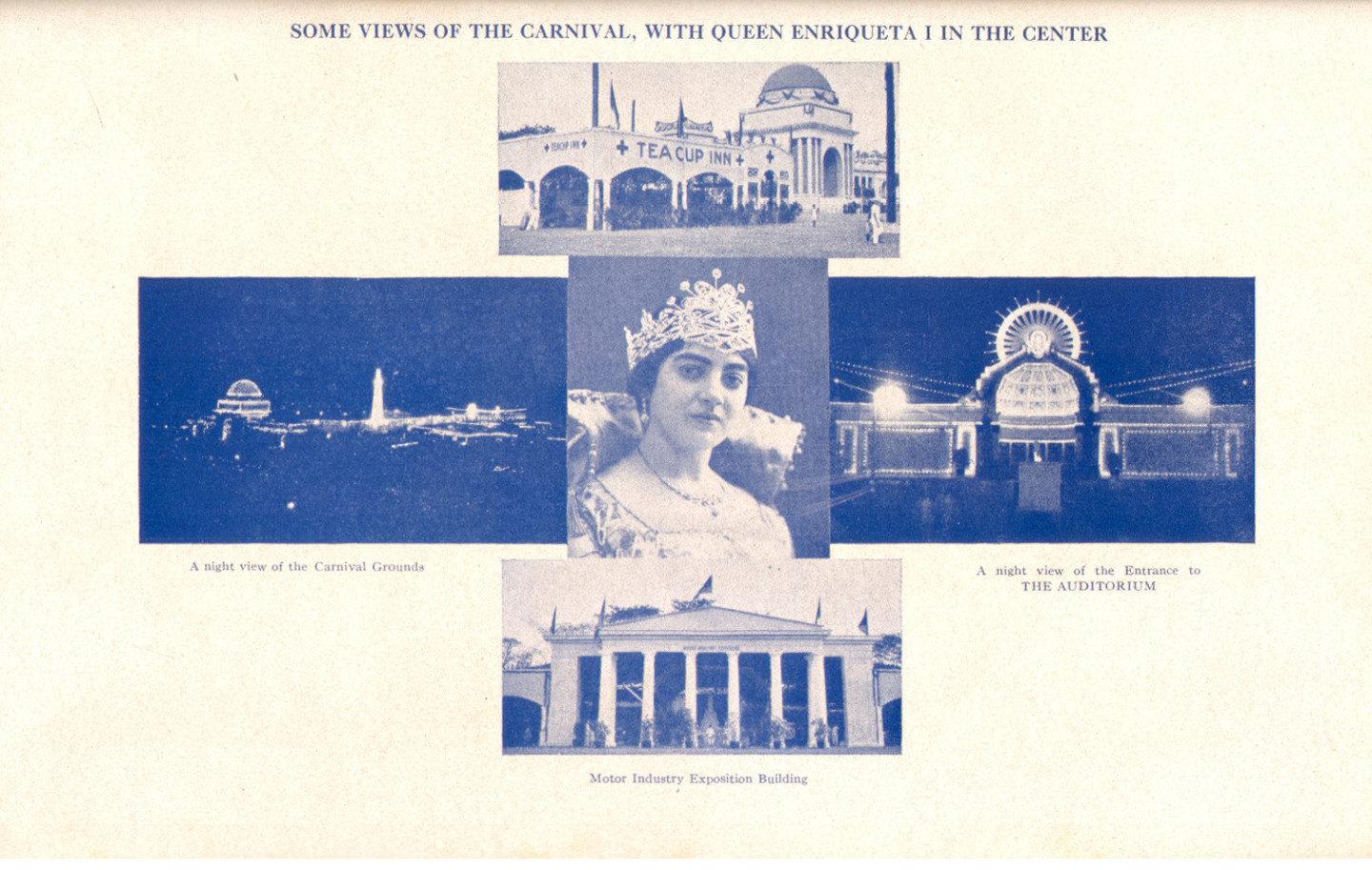

The Manila Carnival took notes from the Mardi Gras and other international festivities, resulting in “nine days of mirth [and] a busy time for costume makers,” said Lacson. Carnival goers were treated to dances and grand masquerade balls, athletic competitions, industrial and provincial exhibits, and the coronation of the Carnival Queen. Tellingly, the carnival’s objectives glossed over the hardships of colonial life, emphasizing instead the colonizer’s benevolence towards its colony and the “good relations between the US and Philippines.”

Fund raising for the infrastructure projects was an “undeclared objective,” Lacson said.

There were 30 carnivals staged annually from 1908 to 1939, with Pura Villanueva crowned the Queen of the Orient in 1908. There were no carnivals in the years 1919 and 1928 and no crowned queen in 1910 and 1911 because it was difficult to choose one. Some of the carnival milestones included the three winners of equal rank in 1912 and 1913 given the regional titles of Queen of Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao; Mela Fairchild hailed as the first and only American Carnival Queen in 1917; and colleges and universities invited to nominate their own candidates in 1929.

The Manila Carnival ignited the Filipinos’ lifelong fascination with coronation,” triggering the holding of carnivals in the Ilocos and in Zamboanga, and spurring newspapers and schools to hold their own contests. The beauty-pageant atmosphere continued even after the official carnival ended, particularly with commemorative events like Rizal Day or Bonifacio Day, in which women who were also-rans in the carnival hoped to finally clinch the crown.

Lacson pointed out that those commemorative occasions should have been “solemn days, but [instead] had a carnivalesque aspect to them.”

Newspapers cash in

Beauty and popularity contests merged into one when the newspapers joined the bandwagon. Candidates were chosen by readers who selected their queens based on photographs sent to and published by the newspapers, with the fairest walking away with prizes of jewelry, inclusion in the Beauty Album sold in the Philippines, Europe, and the United States, and even a car.

The periodicals’ contests had specific themes: Kikirika had “Timpalak ng Kagandahan ng Kikirika,” El Debate sponsored “Ideal Filipina,” Sampaguita organized “Ang Mutya ng Cosmos,” and Cable News American ran “Who are the popular ladies in the Philippine Islands?”

Clubs and specific advocacies of educational institutions also held their own pageants, such as those working to eradicate tuberculosis. Fortunately, they named the winner “Queen of Mercy” and not the unappealing “Miss Anti-tuberculosis.” Even children had their own pageants, with a promoter who organized one for 10-year-olds; the winner was called “Her Midget Majesty.” which, quipped Lacson, would have been cancelled today for being politically incorrect.

What about male beauty pageants? The Philippines wasn’t ready for it. The contest for the most handsome man in Manila, by the Sunday Sun and Filipino Handsome Tournament of Philippines Free Press (PFP), fizzled out quickly as it was launched.

“Contests would tend to make our men effeminate. It’s not beauty and effeminacy that should make us proud of our men, but virile qualities of mind and body,” said Lacson, quoting Gabina Carpio of the PFP.

Scandals

The Carnival Queen’s journey to Queendom was rife with challenges and scandals that Lacson exposed after pulling back the curtain of gaiety and entertainment. A primary — and perennial — obstacle for the impecunious queen-candidate, team, and supporters was money, which was of little or no concern to well-heeled candidates. Money talked and gave a candidate the much- needed royal appurtenances of “gowns, publicity materials and, those determined to get the crown, the right number of ballots.

Ballot buying, known then as the newspaper coupon scam, was a major scandal because “people were also creating their own blots for their candidates,” Lacson said.

Tellingly, a candidate was reliant on what Lacson referred to as “a principal leader to maneuver [the] candidacy and whose responsibility is to secure ballots” to win the pageant. That women from high society could easily secure ballots led to “bickering and backstabbing” because ugly was still ugly no matter the vast number of ballots obtained.

Lacson, quoting Angel Moreno of Graphic, summed up the tense and awkward atmosphere: “It must be embarrassing to sit on the throne, where you’re the feature of attraction. People look at you, stare at you and if you’re not of the near-to-Venus type, they laugh at you. That’s one of the ordeals of being a beauty queen.”

Superstition also found its way to the beauty pageant, with candidates gripped with fear about the alleged Miss Luzon curse: “Nobody wanted to be Luzon because something happened to her. One was kidnapped.”

Wearing a bathing suit became a bone of contention in 1930. The contestants were asked to wear one — after it became vogue in the United States — to “showcase Venus [de Milo]” before the judges during the final selection of winners. This proved divisive, splitting Filipino women into the polarizing dichotomy of traditional vs modern types, a debate on Filipino morality that still rages today.

Beautification campaign

The modern Filipino picked up the gauntlet and wore the bathing suit. Aside from eclipsing the quotidian pageant quibbles, showing skin transcended the restrictive Maria Clara paradigm of womanhood. It encouraged women athletes to ask to be allowed to wear shorts while engaging in sports. However, as the wave of modernity inspired women, another force was rising to reinstall them back to their former position.

“Beauty became for sale,” said Lacson. “There was an increase in beautification. [The point was] even if the women were out in the world, they had to be beautiful through cosmetic products. Manila women were spending P12, 000 a month on products in 1934.”

She added, quoting Rodrigo Lim of Graphic: Beautification was needed because “in every woman’s heart, there’s a burning desire to be admired, fondled, loved. To attract men is her constant aim; to be adored is her ultimate aspiration.”

The demand for beauty products led to an increase in beauty services such as “beauty salons [that] mushroomed all over the capital for all women regardless of social class.” Beauty schools were established — i.e., the American School of Beauty Centre — and new services like the face lift became popular. The job of beauty adviser was also created along with the rise of the beauty empire, which, Lacson lamented, had women being caged in (again)” and made to fit the beauty standards.

Filipino vs Filipino

If World War II hadn’t loomed over horizon 1939 wouldn’t been the last year the Manila Carnival crowned a Queen, but the legacy remains. It’s in the Filipino fanaticism with beauty pageants, the concept of beauty, and the sempiternal debate on Filipino womanhood traditional vs modern, mestiza vs Morena, Maria Clara vs modern woman, Manileña vs provincial lass.

Discussions of beauty pageants have almost always elided social class division and discrimination, but Lacson exposed them and other issues. She spotlighted the geographical hierarchy that pageants fostered when beauty was made Manila-centric, resulting in “people from the provinces [wanting] to be Manileña” in order to gain an advantage over those who weren’t.

The social class divide deepened, with the rivalry escalating and focusing on the differences in the pageants that women joined. The queens from the “inferior or “low class pageants” weren’t from wealthy families or boasted Spanish relations and ancestry.

Equally noticeable was that no one questioned the proliferation of beauty pageants. Apparently, it wasn’t lost on the bankrollers that pageants were huge money-making enterprises, with, said Lacson, “periodical owners [sustaining] the popularity of the pageants because the newspapers made money from the coupons sold.”

The debate on morality had a blindsiding effect. The wearing of a bathing suit galvanized women’s resolve to join a pageant, with winning the crown the primary achievement, especially with what was at stake. On top of the “I am Queen” bragging rights, the precursors of today’s influencers raked in the money with their endorsements. Significantly, the triumphant Queen’s status was elevated, giving her access to society’s elite and opening up important connections for her. Eventually, Lacson said, the Queen either “[married] a rich man” or ended up as a querida, as most did.

Still, the Queen’s new social status was problematic. While joining a pageant enabled women to venture into the public sphere, they faced the stifling mandate of “looking cosmopolitan but also traditional.” The beauty standards morphed into biblical commandments and further widened the social gap between women as, said Lacson, “queens became a measuring stick for what was beautiful. Beauty…became a matter of social status and who knew.”

Before concluding her lecture, Lacson said: “Beauty a gift or a curse? It’s a complicated issue because of the various standards of people.”

It got me thinking of how beauty had been used. These were the thoughts in my mind: “Pulchritude has always been weaponized and used against women. Capt. Langhorn pushed the American agenda with it, while newspaper own or financial gain. Beauty pits woman against woman, dictating their worth and place in society. It’s still happening to this day, with women — unknowingly or not – upholding it with gaslighting, body shaming, mean remarks, etc. on other women. The ‘various [beauty] standards’ of people continue to frame women’s presence and voice. Admittedly, men have biased standards to live up to, but these are nowhere as oppressive as the ones used against women. Beauty based on standardized criteria of aesthetics will never be not prejudiced because differences are never acknowledged.”

People are unaware that discussions must be rooted in history because opinions are not formed on their own but shaped by place, time, and, most important, social institutions. “Ode to Pulchritude” pulled beauty back from the sidelines and brought it to the fore.

Visit Lopez Museum and Library’s Instagram @lopez_muse for the remaining “Culture Intersections” lectures scheduled until the end of September.