Anxiety and depression constantly piggyback on those sidelined to society’s peripheries, like the members of the Filipino Deaf community. Their visibility is hampered, so much so that the number of deaf employees at commercial establishments can be counted on one hand. I’ve seen them only at Frutas in Robinsons Magnolia, Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf on Tomas Morato, and Overdoughs (OD) Café in Greenhills Promenade Mall.

This isn’t an unfamiliar situation for Genevieve Diokno, who, being born deaf, was reminded ceaselessly of her limitations when she joined the work force.

“There was no encouragement to grow and develop,” said Diokno, the co-founder of Hand & Heart signing, which her colleague, Amber, interpreted at “The GoOD Sign” in OD Café on Oct. 28. (Amber learned to sign at eight years old to converse with her deaf friends.)

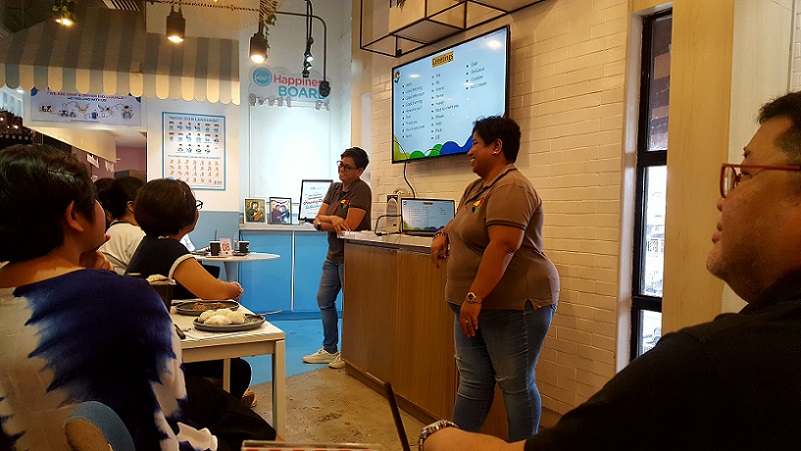

“The GoOD Sign” is a bimonthly deaf awareness and basic sign language seminar organized by Caravan Food Group Inc. (CFGI), with Hand & Heart and De La Salle College of St. Benilde – School of Deaf Education and Applied Studies (DLSCSB-SDEAS) alternating as facilitators.

CFGI launched it in September 2022 in line with Deaf Awareness Month, aiming to bridge the hearing and non-hearing communities, according to Anna Littaua, CFGI’s marketing manager.

The seminar was my introduction to the Deaf community that helped correct common misconceptions — for example, that being deaf means being abnormal, or silent. “We’re not quiet naturally,” said Diokno

Silent world

Amber led an ice-breaker before Diokno’s lecture on deaf awareness. Guessing what Amber recited silently seemed easy. Everyone was quick to guess the first sentence (“I’ve eaten too much sugar today”) but not the second (“I spoke too soon”). The third (“Let’s find cupcake and eat it”) proved too challenging to decipher.

Amber’s questions in a mix of Tagalog and English after the ice-breaker hushed the din: “What’s the feeling? Was it difficult?”

Everyone was at a loss for words, confronted by the uncomfortable truth that their few minutes of frustration are a lifetime struggle for their deaf counterparts. Mine was compounded by my cluelessness on how to interact with them correctly. For example, should I write it down or point to the menu when I order? But isn’t pointing rude? Should I enunciate so they can lip-read? Do I assume they read lips? Do I wait for their hearing colleague to come? How do I say “hello” or “thank you”?

Diokno, an alumna of the Southeast Asian Institute for the Deaf, used her life as a springboard to talk about her community.

“I wasn’t happy with my experiences at work,” she said. “I was told I had potential, but I’d always worked as either an encoder or assistant. I wondered how it was to be in a society that’s inclusive. If the hearing can do it, why not the Deaf?”

Society today is unjustly demarcated into the hearing who see only the Deaf’s disability, and the Deaf who cry out to be seen as capable, not disabled. Unknown to most, the Deaf have difficulty accessing information and communications, and thus are always cut off from music, movies, announcements in school and hospital, and getting help during an emergency. This leads to isolation dovetailed with anxiety and depression.

Diokno was motivated by her family and her will to survive to succeed in the grim environment.

“I continued to work even if I wasn’t happy because I wanted to help my family and to feel useful in life,” she said in a follow-up email interview. “I continued to say ‘yes’ to opportunities to grow that came my way. I was blessed to have hearing advocates that gave us opportunities, which I grabbed, and led me to meeting my hearing co-founders [of] Hand & Heart.”

The Deaf are deserving of rights such as equality, diversity, inclusion, justice and respect, she emphasized.

Breaking barriers

Diokno and hearing partners Dave Mariano and Eylse Go started Hand & Heart in June 2018. Per its website, Mariano was looking for resource persons for his graduate-studies thesis on employment of persons with disabilities (PWDs). His serendipitous meeting with Diokno led to the disability services organization, with the goal of improving the lives of PWDs through work support and transition placement, as well as core services focused on their education and employment.

Mariano and Go are the organization’s business development managers, and Diokno is the general manager. They are also volunteer advocates — sign language interpreters, sign language teachers, and deaf awareness lecturers.

A major obstacle that they had to overcome in setting up Hand & Heart was “breaking beliefs and lack of awareness of the [capabilities] of PWDs [which] took a lot of explaining and orientation [about] our talents and skills.”

The Deaf’s exclusion from the mainstream community is rooted in society’s “traditional beliefs…on what we can and can’t do based on age, gender, orientation,” Diokno said. She said a PWD had to battle “a lot of misconceptions, [and] we’re trying to break the stigma right now.”

With financial stability a pressing problem for Hand & Heart, Diokno said, she’s had to dip into her personal savings to help defray its daily operation expenses. She’s hopeful in finding “grants or regular sponsors for what we do,” which, in the long run, can help put up “a school for the Deaf kids…that’s technology aided, and ready our Deaf for the Digital Age,” she said.

Social responsibility

An impetus for CFGI to help the Deaf community was the sense of social responsibility and inclusivity of its CEO, Francis Carl G. Reyes. He incorporated advocacies for the community when he started CFGI in 2017, guided by a vivid memory of the sincerity of a deaf staff assisting him when he was shopping, said Littaua in an e-mail interview.

To foster inclusivity and diversity, CFGI, per Littaua, has 50 percent PWD and hearing employees deployed throughout its stores, i.e., Elait! (artisanal ice cream), OD (café, coffee, and pastries), Raw (natural juice bar), and Mary & Martha (bangus sardines and empanada).

CFGI’s initiative hasn’t gone unnoticed. According to the company profile, it was recognized at the 22nd Quezon City Council Awarding of Resolution No. SP-9228 series of 2023 on June 05, 2023, for “promoting and fostering more inclusive and accessible work environment for [PWDs].” A month later, it was given the Apolinario Mabini Award (small company category) for “prioritizing the hiring of PWDs and [advocating] working and communicating with the Deaf through Filipino Sign Language (FSL).”

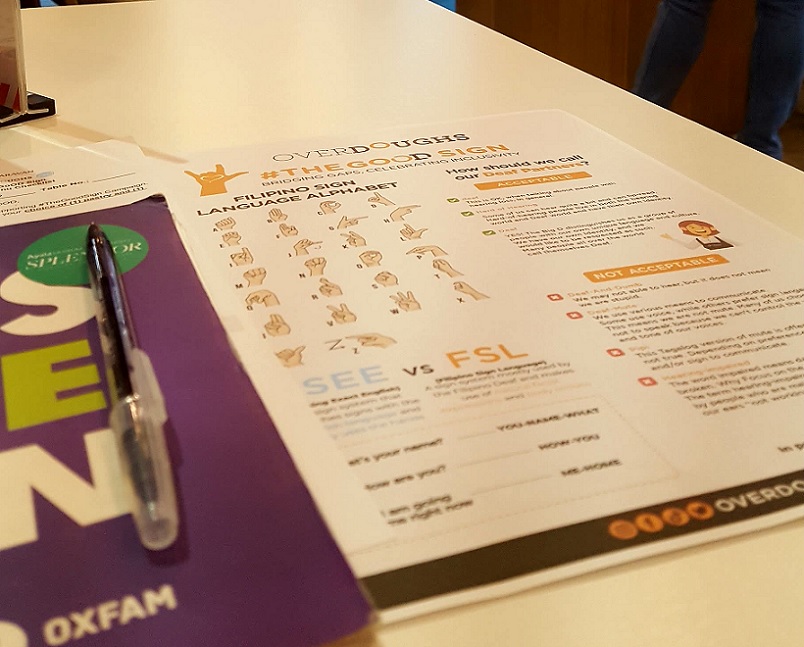

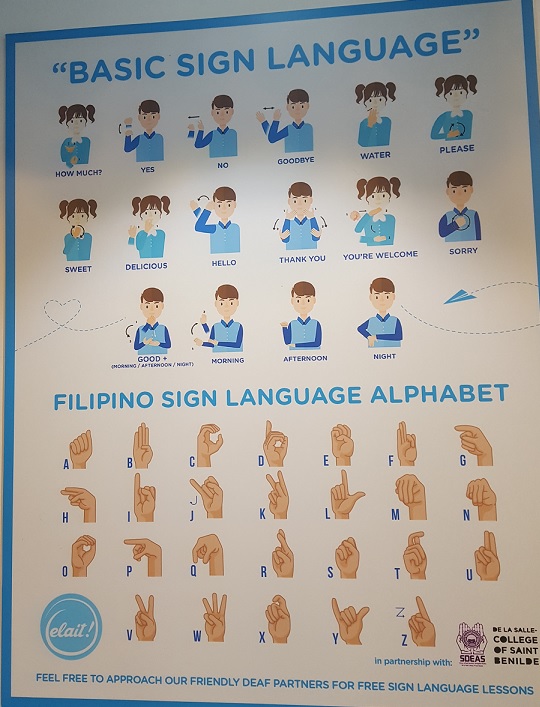

To push the Deaf’s accessibility to education, stores have basic sign language materials (poster, bookmarks and stickers of FSL alphabet) and “menu talkers” for easier interaction between the customer and Deaf staff. Part of the materials is a brochure of DLSCSB-SDEAS’ deaf education programs, i.e., Bachelor in Applied Deaf Studies (study of the Deaf’s identity, language, culture, and communities); Bachelor in Sign Language Interpretation (to become a professional sign language interpreter); and FSL Learning Program (competency in sign language communication).

CFGI also launched “The Good Cookie Project,” a fund-raiser, in May 2019 of which “a portion of the sales went to supporting deaf students and teachers of DLSCSB-SDEAS. The project raised P331, 243.49,” Littaua said, adding that its next rollout is still under review.

Official sign language

The Deaf community got a badly needed shot in the arm when the FSL Act, or Republic Act No. 11106, was signed into law in October 2018 by then President Rodrigo Duterte.

Per www.pna.gov.ph, RA 11106 mandates FSL as the government’s official sign language in all transactions involving the Deaf. It’s also the official language of legal interpreting for the Deaf in all public hearings etc., and in the civil service and all government workplaces, health system, public transportation, services and facilities, etc. It’s to be used in schools, broadcast media, and workplaces, and taught as a separate subject in the curriculum for deaf learners alongside reading and writing in Filipino, other Philippine languages, and English.

Per a philstar.com report, the FSL Law also directs the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster sa Pilipinas and the Movie and Television Review and Classifications Board to have FSL interpreter insets in news and public affairs programs within one year from the effective date of the law. Similarly, the law requires courts to have a qualified sign language interpreter present in all proceedings involving the Deaf.

However, signing into law and implementation are two different cases. RA 11106’s full effect has yet to be realized because the Inter-Agency Council (IAC) only approved the Implementing Rules and Regulations in December 2021. This was discovered by the House of Representatives’ committee on PWDs chaired by Negros Occidental Rep. Ma. Lourdes Arroyo, as reported by PNA. Nonetheless, Arroyo cited the IAC’s action, saying the FSL Law can help the Deaf community finally have access to information and communications.

It’s a sentiment shared by Diokno, who said the FSL Law would help push for Deaf rights and bring about “more awareness.” Still, her fingers are for “the full and fast-tracked implementation of the law.”

Deaf awareness 101

I find that labels are the starting point on deaf awareness in the hearing community. The spoken words shape the perception and identity of a subject. Phrases like “deaf and dumb,” “deaf-mute,” “pipi” (Tagalog for mute), and “hearing-impaired” are pejoratives, according to the seminar handout. Acceptable terms are “deaf” (for general use), “hard of hearing” (some can hear a bit and lip read), and “Deaf.” The capitalized D is important because it distinguishes them as a group of people with their own unique language and culture.

The handout stated unequivocally: “We may not be able to hear, but it doesn’t mean we’re dumb. We use various means to communicate. Some use voice while others prefer sign language. Many of us choose not to speak because we can’t control the volume and tone of our voices.”

Knowing if a person is deaf or hard of hearing can ease the awkwardness. Diokno enumerated the common signs: a tendency to sit forward, with an intense facial expression; watching people’s lips; turning an ear toward the speaker; misinterpreting words and asking people to repeat statements; responding to a raised or loud voice; and speaking loudly while complaining that people are mumbling.

Using visual signals is prevalent among the Deaf, she said: “Communication is generally very expressive, i.e., facial expressions, eye contact, and body language. All are vital elements of sign language.” (FSL uses natural facial expressions and body actions, unlike Signing Exact English, which only uses hands, according to the handout.)

The Deaf’s etiquette on speaking says it’s inappropriate to shout at them and refuse to communicate with them upon finding out they’re deaf. Never mimic their actions of signing when you don’t know how to sign because it’s grotesque mockery.

How do you communicate with them if you can’t sign? Counseled Diokno: “Write. Face us when you’re talking. Tap the shoulder or the floor — the vibrations can be felt. Wave or use any light source by switching it on and off to get our attention. Use body language, gestures, and facial expressions. Deaf people are visual [so] use technology and social media, and places with good lighting.”

For employers who’ve hired deaf workers for the first time, Diokno said, “It’s important to demonstrate the instructions to them.”

To stop them signing, switch off the lights, she said, triggering laughter in her audience.

Moving forward

The journey to inclusivity continues even if at turtle pace and strewn with challenges. There’s still the gap between the hearing and the Deaf community, but CFGI assiduously tries to bridge it with “partnerships, advocacy, and awareness campaigns,” said Littaua.

Comparatively, there have been breakthroughs in the Deaf community, particularly in employment. Per Littaua’s assessment: “Other companies already have similar initiatives promoting inclusivity in the workplace [and] more companies are actively contributing to deaf awareness. The perception of the Deaf among the hearing has gradually [shifted] towards more understanding and acceptance. Events like ‘The GoOD Sign’ seminar play a crucial role in fostering empathy and awareness.”

She continued: “The response to [‘The GoOD Sign’] was overwhelmingly positive. It was great to know that there are a lot of people willing to support the importance of the cause.”

Similarly, Diokno is gladdened by the current landscape where “diversity, equality, and inclusion are becoming a priority agenda with the help of the United Nations’ sustainable goals…, the socially conscious young professionals, and passing of laws that encourage the hiring of PWDs.” But she declared in the same breath that more has to be done for “better access to quality education for the Deaf in order to ensure [a] better future.”

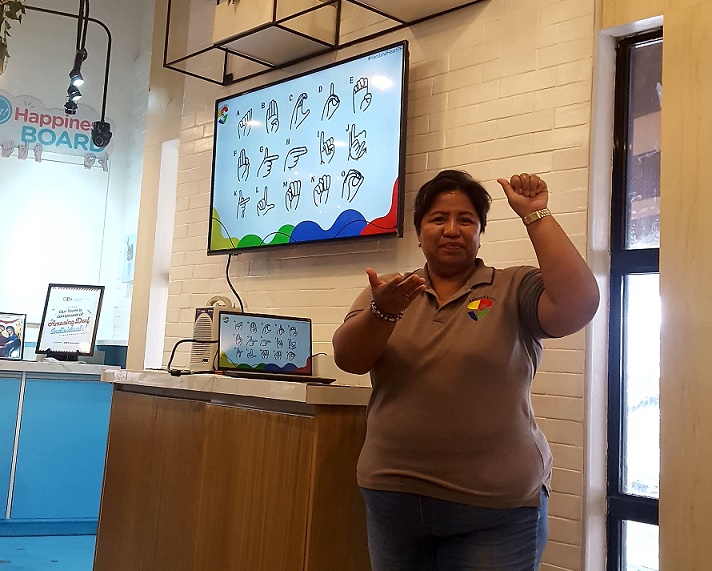

Soon it was time for the introductory sign language lesson with Annalyn, instructor at Hand & Heart’s basic signing language classes and former Benilde scholar. Throughout the lesson, she scanned the room, caught mistakes, and corrected them (like my misplaced fingers for the greeting “How are you”, the letter D, and numbers with six in it).

Determination and attending proper classes are key to learning how to sign. With these two, I’ll be signing fluently in no time, leaving no one out from conversations, whether hearing, deaf, or hard of hearing.

Visit Overdoughs Café’s Instagram @overdoughsph for the schedule of “The GoOD Sign” this November.