Images courtesy of Felice Prudente Sta. Maria and Google

How do you cook your bistek or biftek?

The earliest published recipe for beefsteak in the country is from a 1913 cookbook (La Cocina Filipina) titled “Beefsteak de carne de vaca” where the thick steak is sprinkled with salt and pepper, moistened with a little water, the onions fried in Manteca de Flandes, and served with an English sauce called John Bull.

Known as Bistek Tagalog, it is cooked today with soy sauce, calamansi, minced garlic and topped with fried onion rings. Bistek has certainly gone a long way since 1913.

Cookbooks are part of our social history, a written record of people’s food habits, reflecting what are considered everyday dishes and what are special or celebratory dishes of a particular period. In many ways, cookbooks serve as windows of a society, tracking cultural shifts and norms.

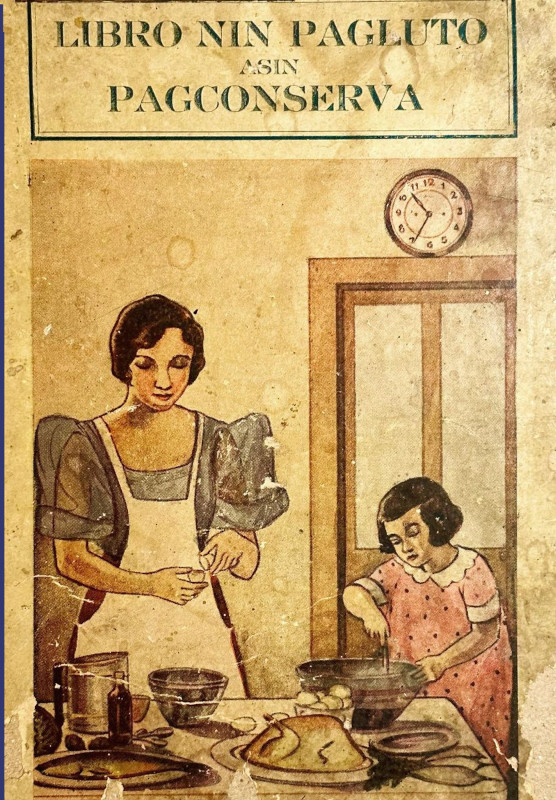

Early Philippine cookbooks

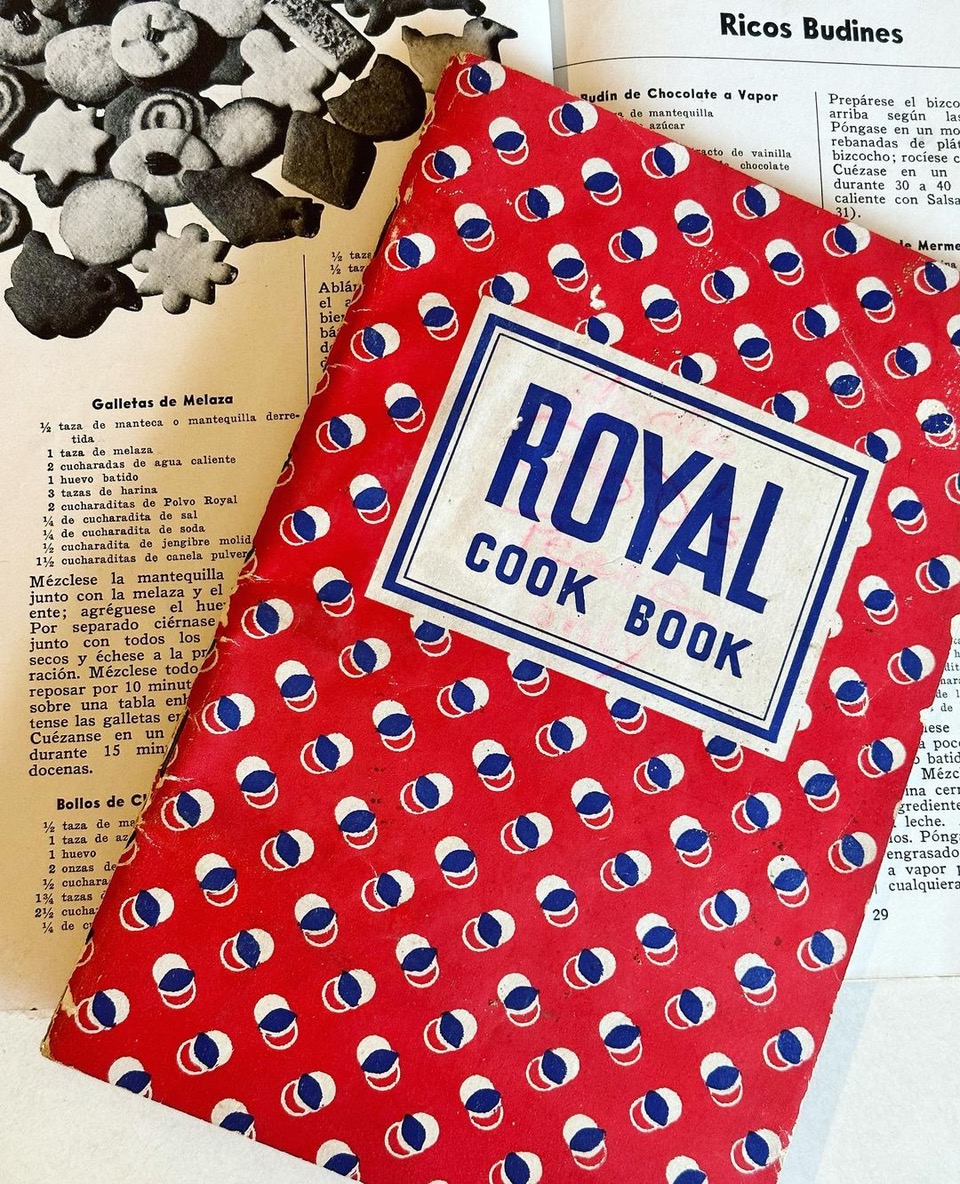

Spanish cookbooks predominated during the Spanish colonial period. Under U.S. colonial rule, the American public school system with its Domestic Science classes led to the printing of more cookbooks and recipes in textbooks as well as cooking classes and demonstrations advertising canned products and home appliances, mostly American.

La Cocina Filipina: Colleccion de formulas practicas y posibles en Filipinas para comer bien (1913) is considered as the first published cookbook in the country. Its Filipino dishes included pansit, lumpia, pesa de galina, sinigang de carne, sotanju, pacsiu de pescado, as well as Spanish and European dishes.

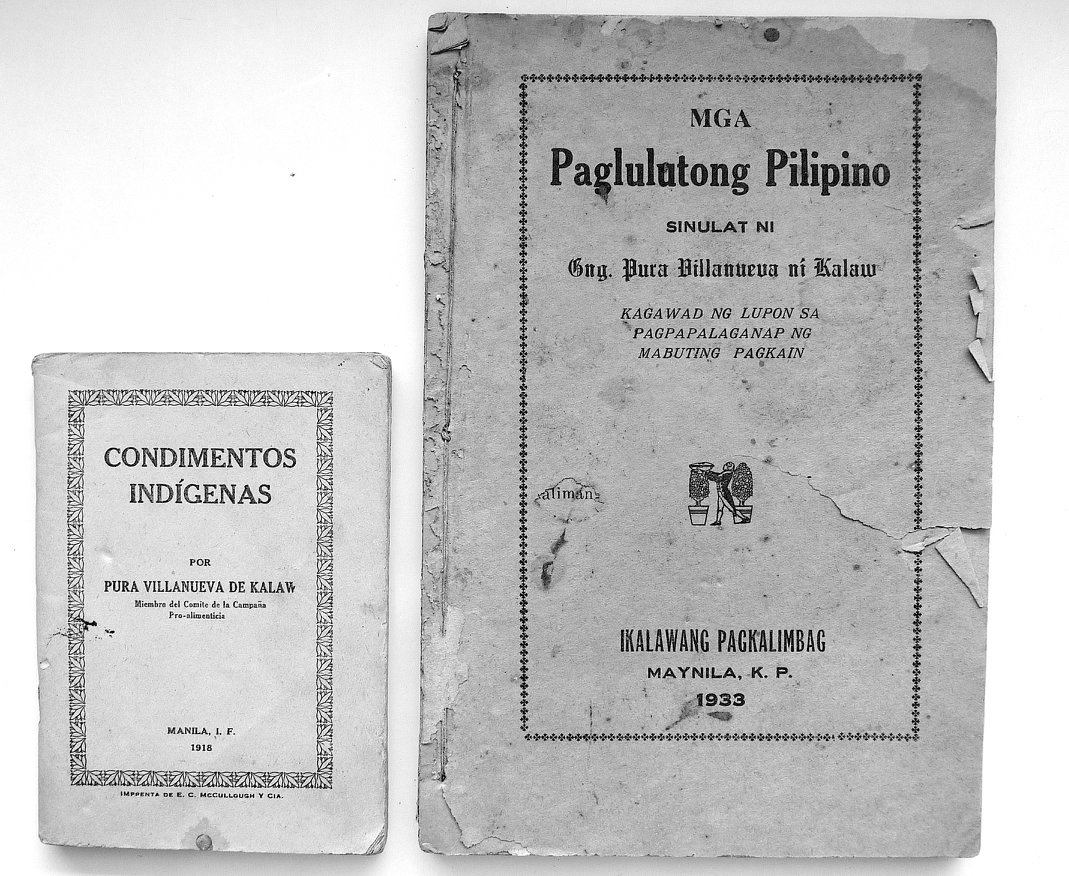

La Cocina Indígenas (1918): Written in Spanish by Pura Villanueva-Kalaw to raise some money for a billiard table for her husband, Teodoro M. Kalaw, who needed some exercise for his wooden leg.

Queen of the first Manila Carnival in 1908, Pura Villanueva Kalaw was a leader for women’s political and property rights, and the mother of the former senator Maria Kalaw Katigbak and Purita Kalaw Ledesma, a writer and art critic who founded the Art Association of the Philippines.

Palm-sized, it included recipes gathered by the author from family friends and those known for their cooking specialties from Batangas, Cebu, Ilocos, Iloilo, Cebu, Pasig, Sorsogon, and Mindanao. It sold very well, and was translated into Bicolano, Cebuano, Waray, Ilocano, Kapangpangan, and Tagalog.

Maria Kalaw Katigbak, in her mother’s biography Legacy, noted that “it was not a simple cookbook. It carried her message of nationalism in the choice of food, in nutrition, in simplicity of diet, and in thriftiness of operation.”

With a total of 154 recipes, 54 were vegetable dishes that included pinangat daragueño, monggo guisado, tauge de mongo, kagios con nanca or KBL, sitaw guisado, relyenong talong, kinilaw puso ng saging, pakbet, and corn soup with malunggay or suam na mais today. Chicken recipes included adobo de pollo with achuete, linaga, kari de pollo, and apritada.

A hundred years later, most recipes in this book are considered standard fare or classic dishes that Filipinos cook to this day.

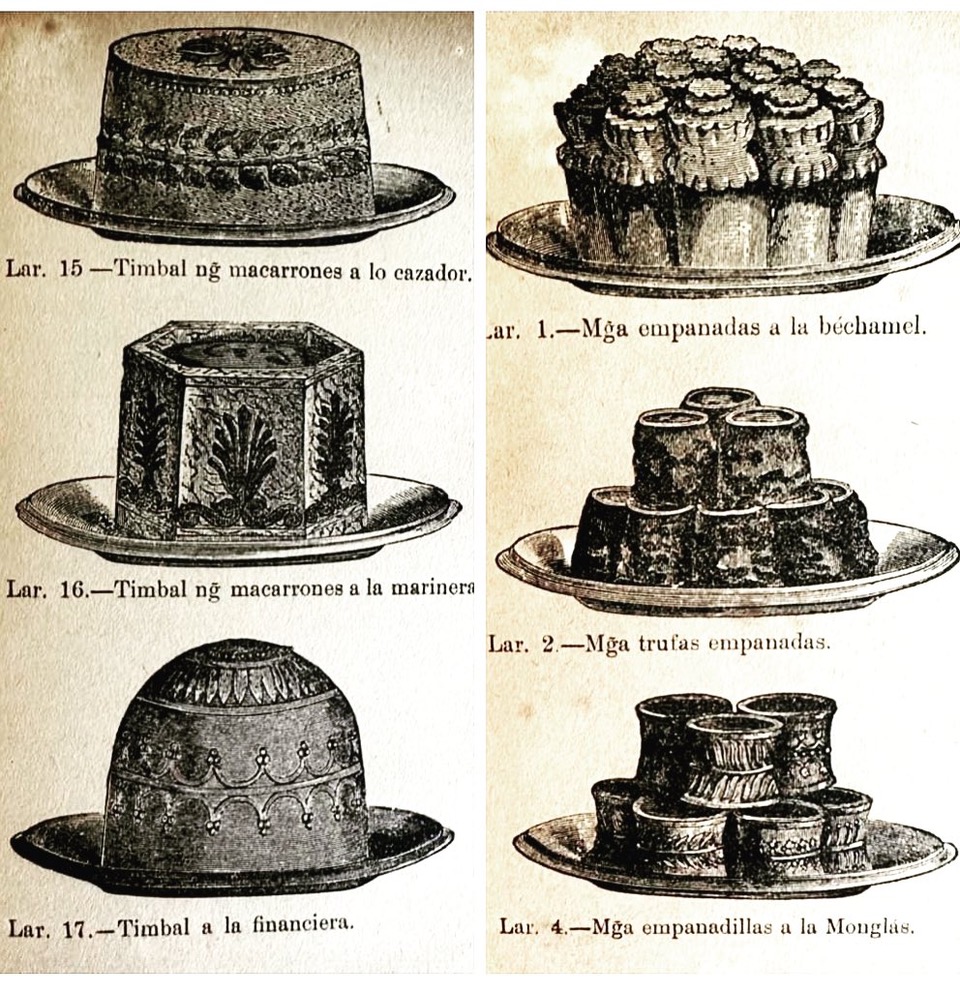

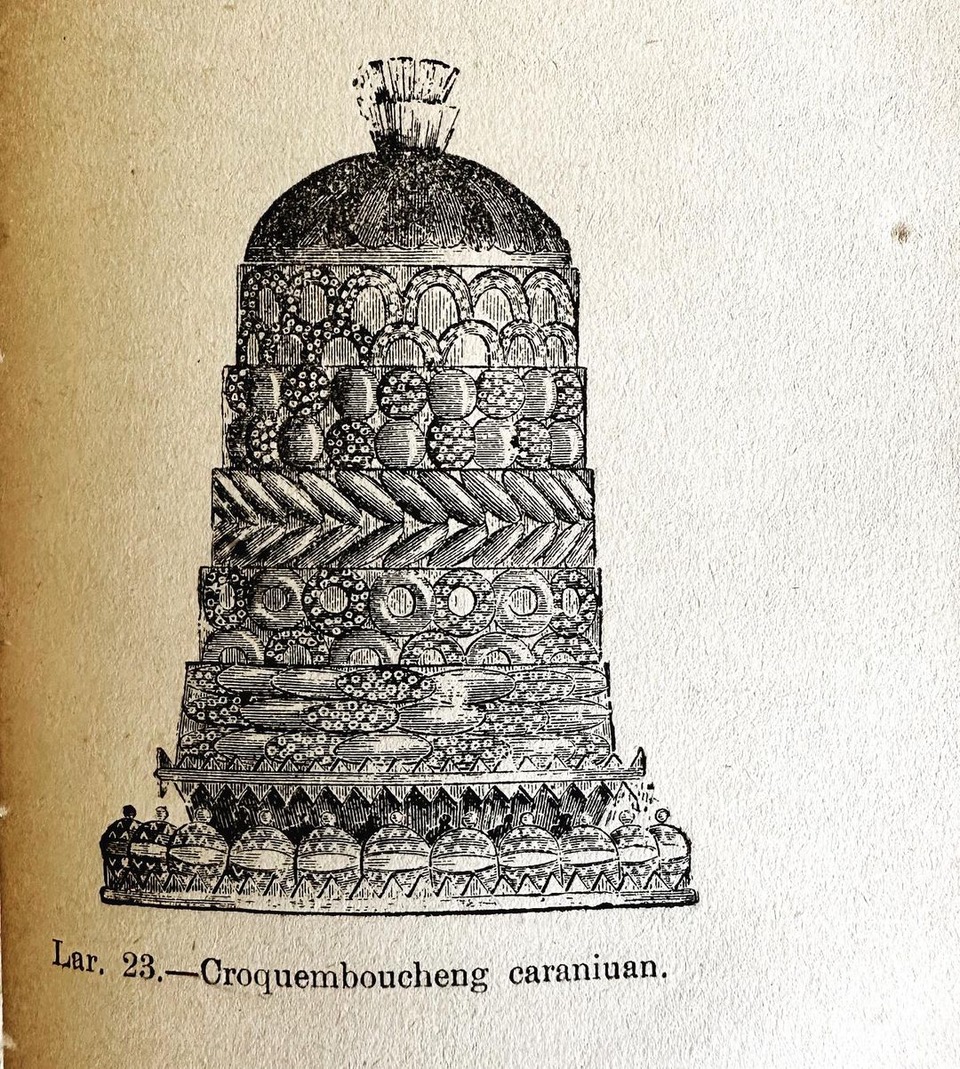

Pastelería at Repostería Francesca at Española (1919): Aclat na ganap na naglalaman ng maraming paglacad at pag-gaûa ng lahat ng mga bagay-bagay na matatamis at mga pasteles, it was written by P.R. Macosta and translated in Tagalog by Crispulo Trinidad.

It consisted of fancy recipes of pastas, pastry, and savoury pies using truffles, anchovies, orange blossom, almonds and pistachios, foie gras, etc. It also featured illustrations of classic French cookery such as croquembouche, a tower of cream puffs, a variety of timbale dishes, as well as different kinds of turrón recipes or nougat sweets.

Doreen G. Fernandez in her book Tikim observed that “foreign cuisine had indeed entered the kitchens and the lives of the Filipino elite of those times.”

Good Cooking and Health in the Tropics (1922): With Elsie Gaches as its editor who was the principal of the Philippine General Hospital School of Nursing, it was published by the American Guardian Association to raise funds for 18,000 abandoned or orphaned Fil-American children.

1930s: The age of recipes

Everyday Cookery for the Home (1930) by Sofia R. de Veyra and Ma. Paz Zamora Mascuñana was mostly filled with American recipes, when “housewives were eager to learn new recipes and new techniques of home economics and nutrition.”

Food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria describes Mascuñana as a culinary icon of the 1930s. Her recipes were most likely the very first Filipino written recipes for sansrival, food for the gods, ensaimadas, Mazapan de pili, or empanadang especial.

Newspapers and magazines such as Women’s Home Journal-World (1920), Liwayway (1922), and Philippines Graphic (1927) started publishing recipes in Tagalog and English in the 1930s.

American manufacturers of refrigerators published cookbooks and recipe booklets, giving them to new buyers of their products. In 1927, General Electric published its “Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes” and in 1936, it distributed “The New Art of Modern Cookery” in Manila.

Nowadays, we can get any recipes online or watch cooking in YouTube, as entertainment. Here to stay, a quick Google search reveals an array of new Philippine cookbooks, local and overseas — all waiting for us to peruse and learn new ways of cooking Filipino food.