Photos by Liana Garcellano

Who’d have thought that academics would succumb to the lure of K-drama during the pandemic? Well, they did.

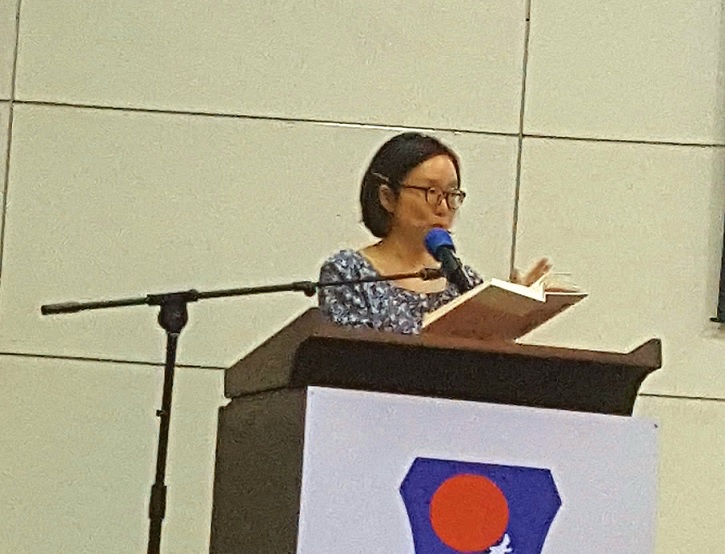

Joi Barrios, senior lecturer at the University of California in Berkeley, said she watched 50 historical K-dramas when Covid-19 was raging. She made the disclosure in a lecture, “What I learned as a writer from watching historical K-dramas,” at the University of the Philippines’ GT-Toyota Asian Center Auditorium on Feb 23.

Similarly, UP Prof. Ramon Guillermo confessed to jumping on the K-drama bandwagon in his opening remarks. But watching K-drama didn’t mean forgoing critical viewing for Guillermo; thus, he highlighted the importance of viewing a pivotal part of hallyu (Korean wave) with a discerning eye. And he wasn’t keen on how K-drama has depicted the Philippines as a hideaway haven for criminals escaping incarceration. (Actor Choi Woo-shik’s “A Killer Paradox” comes to mind. His character flees to the Philippines after committing a series of murders in Korea.)

“More than the interest in K-drama and culture, it’s important for us to know how to give [significance] to one’s language and culture… [and] learn the positive aspects of Korean nationalism against Japanese imperialism,” said Guillermo, director of UP’s Center for International Studies (CIS).

In her lecture, Barrios discussed the use and subversion of courtly love conventions, women’s discourse, and the pleasure of viewing vis-à-vis historical memory in critiquing the Philippines’ current state.

The lecture was jointly organized by the CIS, Departamento ng Filipino at Panitikan ng Pilipinas, Kolehiya ng Arte at Literatura, UP Asian Center, and UP Korea Research Center.

K-drama community

The auditorium that morning rang with chuckles from bona fide K-drama viewers when Barrios flashed the Korean finger heart at the start of her lecture. Hands were quick to rise, too, when she polled the number of K-dramas they’d watched.

“We’re a community because we’re bonding. We can chit-chat about K-drama, do the Korean heart sign. There’s even merchandise (to buy) like T-shirt, blanket, cookbook, etc.,” said Barrios.

The strong inclination to watch K-drama is real, and Barrios enumerated, in a mix of Filipino the reasons for the addiction: quality storytelling, diverse themes, female-centric narratives, and global accessibility (dubbed or subtitled).

“But Netflix’s English subtitles are problematic, though,” she quipped.

The rules of love

Historical K-dramas are replete with the theme of love and its conventions, which Barrios listed on her PowerPoint slide. For example, the unrequited love of Kimura Shunji for Oh Mok Dan in “Bridal Mask” (2012); the forbidden love between Bae Yi-hyun and Song Ja-in “Nokdu Flower” (2019); the secret love between gisaeng (courtesan) Cha Song-joo and revolutionary police Lee Soo-hyun in “Capital Scandal” (2007); the unspoken love in “Different Dreams” (2019); and the wartime separation of lovers in “Nokdu Flower” and “Different Dreams.”

Forbidden love is a common trope in K-drama, which follows the 12th-century romance conventions outlined in the book “The Art of Courtly Love” by Andreas Capellanus.

“In courtly love, love rarely endures when made public. A lover’s heart palpitates when he catches sight of his beloved, and love can deny nothing to love. In the Middle Ages, people got married not for love,” Barrios said, explaining Capellanus’ concept.

Marriage was done for social or political reasons, and thus, love in a marriage was more an exception than a rule. People found love outside of marriage, resulting in an adulterous relationship, according to www.arlima.net. By modern standards, the affairs of medieval times were not scandalous but quite tame because they weren’t physical, and basically involved flirting, dancing, and the chivalrous efforts of young noblemen and knights in currying favor from the ladies at court, said study.com.

Barrios said the forbidden-romance trope had K-drama lovers meeting secretly in a garden or by a lake at night, and writers went either conservative or anti-conventional in introducing romance. The former established the lovers’ relation sans physicality through the “memory connection” — they had a past they didn’t know or remembered.

The latter used “the fall” to effect romantic tension, with the woman literally falling and the man catching her, resulting in their briefly holding each other.

Barrios’ first lesson from watching K-drama — translated into English — is this: “It’s important knowing the conventions but also breaking them.” The conventions of love were subverted with the show of respect for one another, and love is redefined as loving everything about the person, she said.

Reacting to Barrios’ lecture as sole discussant, Prof. Kyung Min Bae pointed out that “the touch of romance in historical dramas was a way to alleviate the viewers’ boredom.”

Kyung, director of the UP Korea Research Center, added: “K-dramas have evolved. Old K-dramas weren’t free because of censorship unlike today [when] they’re freely produced [and] tweaked according to the viewers’ opinion. There’s diversification these days, touching on the marginalized sectors of society, including women.”

Women’s discourse

K-drama has made inroads into feminist discussions with the characterization of women. They refute the stereotypical depiction of women as weak or scatterbrained damsels in distress or curmudgeons. Thus, Barrios’ second lesson is that “discourse on women — whether pop culture or not — should always be included.”

“K-drama is women-centric,” Barrios said. “Most characters are trailblazers, i.e., lawyer (Woo in ‘Extraordinary Attorney Woo’), surgeon, historian (Goo Hae-ryung in ‘Rookie Historian Goo Hae-ryung’). Historical dramas emphasize women who serve the nation and place importance on independence.”

Tellingly, the women characters defy what Barrios theorized as the Cinderella persona. Instead of the women dreaming of heading to the palace — the seat of power — they leave the palace so they can be themselves and serve ordinary people.

A pivotal element for feminist discourse is the modern vs traditional representations of women, or the binary opposite. Barrios cited the character of Na Yeo-kyung in “Capital Scandal” who was fighting for Korea’s liberation from Japan instead of dating, like most of her contemporaries. She challenged and changed Sunwoo Wan — who’s interested in her — from a carefree playboy into an independence-movement activist.

Offering her insight on “Capital Scandal,” Kyung said “modern girl and modern boy” was how awakened or politicized Koreans were called during the Japanese occupation of Korea.

The professor went on to highlight that K-drama is the women’s imagined space that shows the possibility of gender equality and women empowerment because gender equality remains a problem in Korea to this day.

Pleasure principle

There’s no comprehending the satisfaction derived from watching K-drama until you take the plunge. To the K-drama neophyte, Barrios named five reasons for the viewing pleasure: sympathetic and lovable characters; the kilig feeling; an element that completes the viewing experience like music; exciting plot; and use of metaphors and memorable lines.

Character development is a significant element because of how the writers give a “clear delineation and transformation of the character,” said Barrios, citing the Japanese who eventually fought for Korea’s independence in “Bridal Mask” and the Lothario who became a freedom fighter in “Capital Scandal.”

“In K-drama, all can join the anti-imperialist struggle and become freedom fighters, including regular people. The women contributed to the movement with their cooking,” she said.

Metaphors and memorable lines being key elements, for Barrios, the metaphor of the blue bird for Japanese colonizers in “Nokdu Flower” was clever while the line in “Bridal Mask” was poignantly provocative vis-à-vis colonial subjects: “You may have invaded us, but you haven’t captured our hearts,” she said.

Historical affinity

The metaphors and lines in K-drama have prodded Barrios to ponder on the colonial history of the Philippines and to remember the revolutionary Jose Maria ‘Joma’ Sison and the time she “read books about Ka Joma that were banned.” Her recollection is linked to her third — and final — lesson in watching K-drama, which, translated into English, upholds the idea of the writer’s discussion of history opening the door for dialogue.

For Kyung, historical dramas are important in K-drama because “they’re used in the education of the next generation.” She qualified, however, that “there are still debates on the historical distortions, i.e., cross-dressing heroines. They’re meaningful because there’s a reinterpretation of history.”

Hereabouts, Filipinos’ penchant for watching K-drama remains strong, propelled by the relatable feelings — pleasure, sadness, kilig moments, suspense. This consanguinity is one of the primary reasons that help maintain the ties between Korea and the Philippines. As Kyung said, “Emotions are universal, you can’t control them.”

Barrios did not deny the affinity by emotions, but said there’s more to the psychological connection.

“[K-drama] makes you think about life and [our] country… The history of Korea is different; the Philippines is different. However, we’re united by a collective stand against colonialism and fight for rights and justice,” she declared in Filipino.

Shortly, to conclude her lecture, she read a poem that she wrote two years ago for Ka Joma, who died last year in the Netherlands.