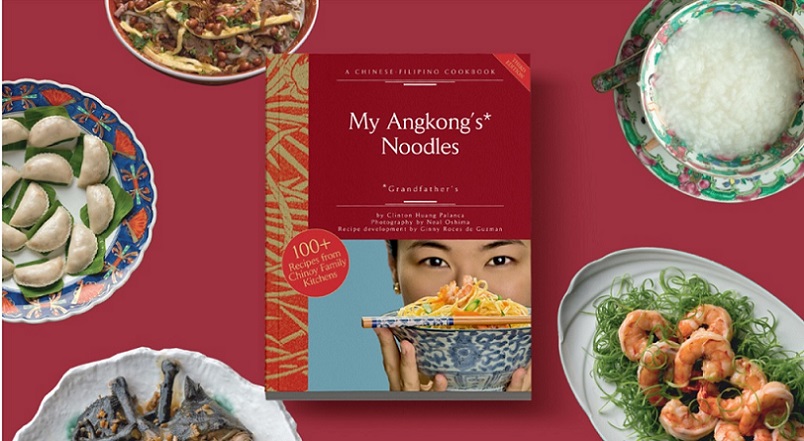

Images of food dishes from the book by R.C. Ladrido

“Chinese food” as a term speaks of its broadness and generality. Which Chinese food are we talking about?

The eight culinary traditions of Chinese cuisine include Anhui, Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan, and Zhejiang, with the use of ingredients shaped by climate, history, geography, resources, cooking techniques —resulting in their distinct tastes and characteristics.

Hokkien food

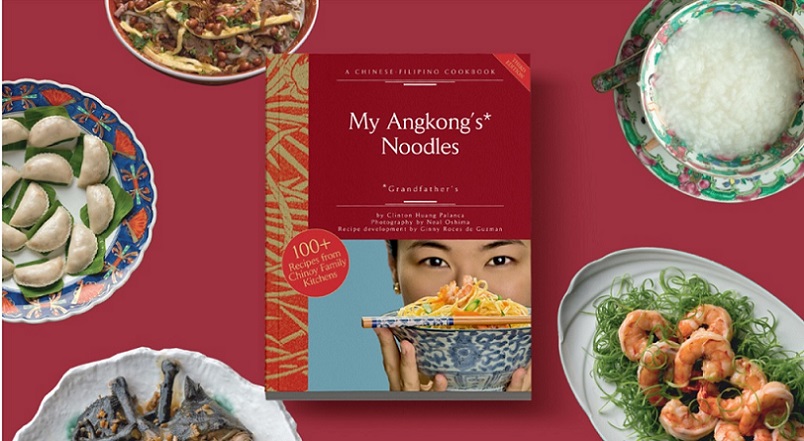

Hokkien or Fujianese food as shaped by generations of Chinese Filipinos is the central focus of My Angkong’s Noodles: A Chinese-Filipino Cookbook (Third Edition). Clinton Huang Palanca. Mandaluyong: Summit Publishing Inc., 2023, 273 pp.

It defines what is Fujian-inspired Chinese Filipino food in the country, with recipes from the kitchens of Chinese-Filipino families. What constitutes good Fujianese food? How do you prepare and cook it?

Clinton Palanca underscored that the book is for an entire generation of Chinese-Filipinos who grew up with “only the vaguest notions of what constituted good Fujianese food,” in his introduction My Food, My Identity.

He noted that while maintaining the spirit of authenticity, they did not try to be faithful to the original mainland Fujian version. After all, “it is a book of Chinese-Filipino recipes and foodways, and the recipes reflect the new world that the Fujianese migrants found themselves in…”.

Originally published in 2014, the book features over a hundred recipes for rice, noodle, seafood, meats, vegetables, and snacks and desserts for everyday eating and celebrations. It also has a chapter each on Innovations & Variations and Medicinal Dishes.

In the 2014 edition, Doreen G. Fernandez writes the preface, Comida China; in the third edition, Ling Chi-Wang, professor emeritus of Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of California-Berkeley, writes the introductory essay.

The book keeps the Hokkien name of the dishes, its traditional characters, and English translations. Published by Elizabeth Yu Gokongwei, all proceeds will go to the educational scholarships of the Gokongwei Brothers Foundation.

For Filipinos, Chinese food has become so much part of our foodways that we do not even think of their Chinese origin, much less of their Fujian origin. Hokkien names of favorite food include siopao, siomai, matsang, misua, and the list goes on. We delight in eating lugaw, roast pork (asado), kikiam (ngo hiong), radish cake, oyster cake, spring rolls (lun pia shiong hai), and all types of noodles, especially stir fried (cha mi) loaded with seafood, bola-bola, and vegetables.

Hokkien influence

“Angkong” in the title means grandfather in Hokkien or Minnan, the speech south of the Min River, or the lingua franca of the Chinese Filipino community, as most of them trace their ancestry from southern Fujian, especially the coastal areas of Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Xiamen.

With some 50 million speakers of Minnan in southern Fujian and Taiwan, it is also the language of the Chinese diaspora in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Myanmar.

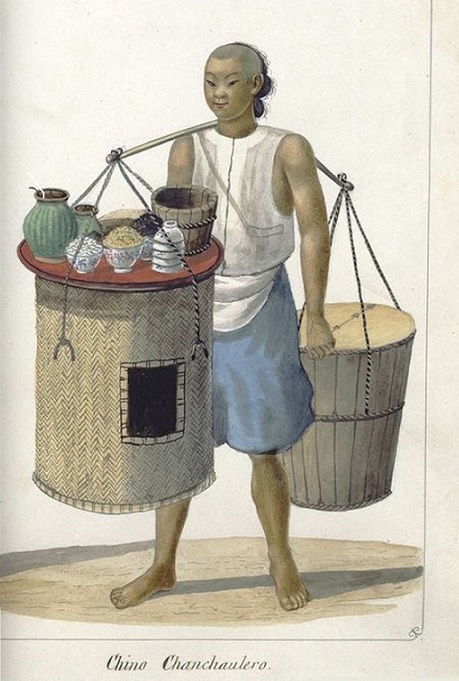

Fujian migrants

Long before 1521, the Philippines and China have had a flourishing trade; direct contact between the two nations existed from at least the Song period (960-1279); by the Ming period (1368-1644), the eastern route of the Chinese junk trading system had been well established, from Fujian to Penghu, Taiwan, Luzon, the Sulu Zone, and to Moluccas.

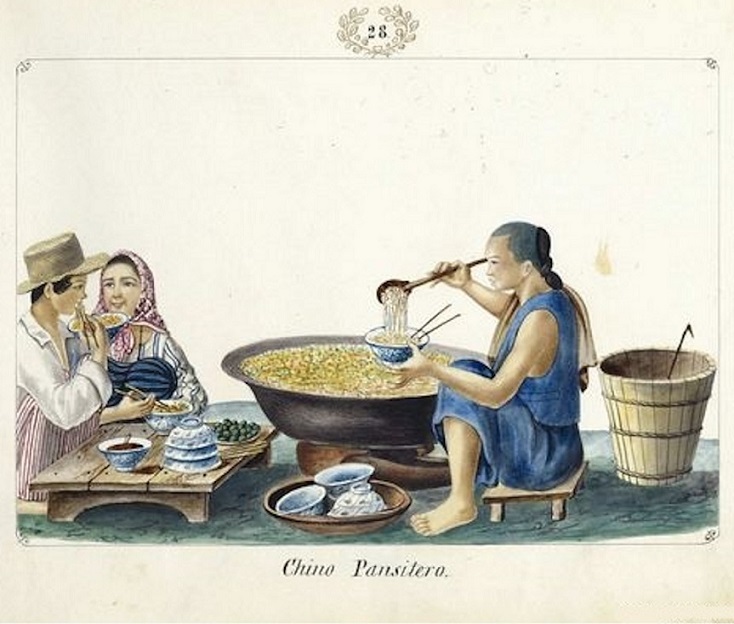

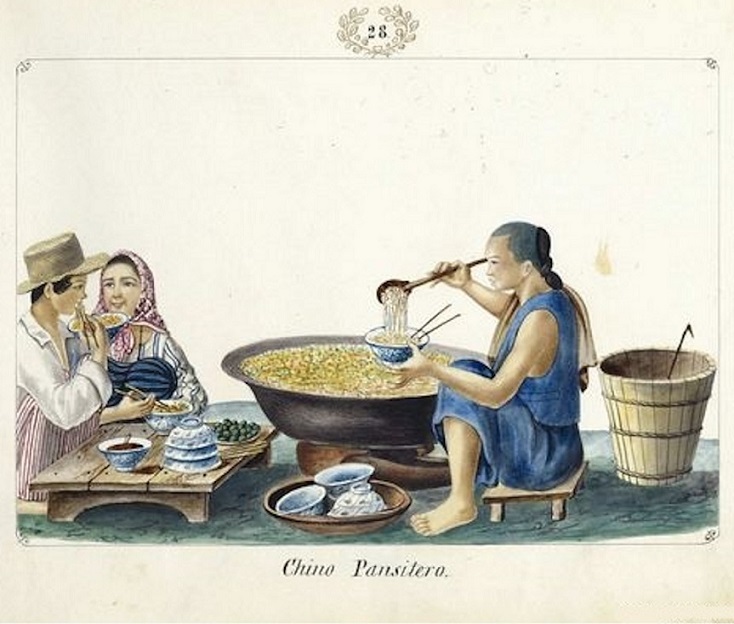

Relations between the two strengthened further with Manila becoming a key Asian entrepot in the trans-Pacific galleon trade (1565-1815) between the Philippines and Mexico. Hokkien merchants dominated the trade and led to the spread of Hokkien communities across the archipelago.

Pancit and lumpia

Two dishes, noodles and spring rolls (popiah) with all its permutations, remain Fujian’s enduring culinary legacy in many overseas Chinese communities today.

Many types of noodles are in the book: stir fried noodles (cha mi), misua with fresh oysters or hebi (dried shrimp) and patola, or misua with kidney and liver; festive noodles such as Sotanghon Crab in Satay Sauce or Zhangzhou-style Noodles are also present.

In the realm of gustatory indulgence, a section includes on how to give a Chinese fresh lumpia party, all handmade, and how to roll one’s own lumpia the right and graceful way. Eating lumpia is “the ultimate celebration of Chinese Filipino commensality,” an affirmation of identity in a meal.

Hokkien loanwords

Gloria Chan Yap’s landmark study (1980) of Hokkien borrowing in Tagalog found that Hokkien loanwords predominate in types of cooking, methods of preparation, and cooking instruments. Food-related words include batsoy, lomi, bihon, swahe, pesa, suam, am; pork cuts (tito, kasim, liempo); soybean products (taho, tokwa, tahuri, tawsi, toyo); and vegetables (petsay, sitaw, toge, upo, kutsay, kintsay, yansoy, etc.), for example.

Clinton Palanca

The author studied literature and philosophy at Ateneo de Manila University, and culinary arts at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris. With a Master of Philosophy in sociology from Oxford University, he was doing a doctorate in food anthropology at the School of African and Oriental Studies in London.

A food reviewer for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, he had also written books of fiction and nonfiction. He died in 2019 at 45 years old.