To say that there’s nothing to gain from learning Philippine history is to ignore Filipino students’ appalling ignorance of their country’s history — a result of an irrational educational system that has students learning history in grade school and then picking up lessons later in college.

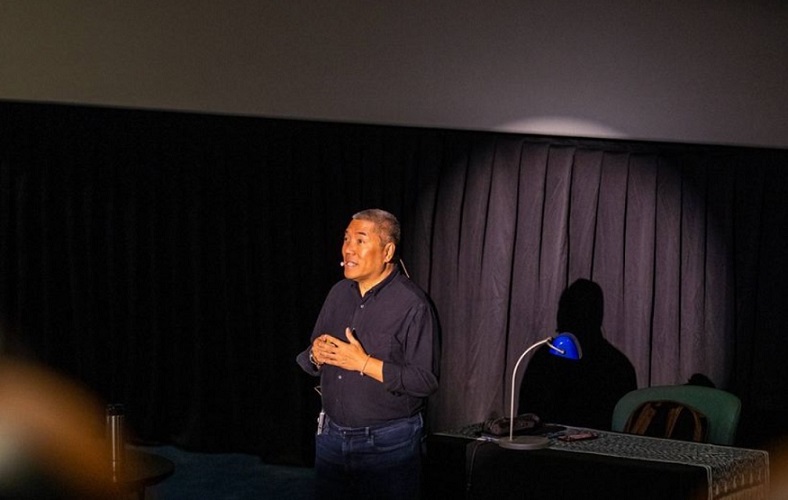

“That’s seven years of no history at all. What will you tell grade school students? Our educational system doesn’t create or teach critical thinking,” declares historian Ambeth Ocampo. He’s answering a query on how to teach Philippine history during the Q&A session of his lecture, “Icons of Philippine Independence: Stories in Artifacts,” at The Power Plant Mall in Rockwell Center, Makati. Presented by Lopez Museum and Library on June 22, it’s his second lecture after “Breaking Up is Hard to do: Philippine American War Revisited” on Feb. 3.

Continues Ocampo: “They want [students] to be obedient. They don’t want people to ask questions because [they’d] be difficult to handle. How do you teach history? Give them facts. History isn’t about being right or wrong. It’s understanding how [Philippine heroes] reacted based on what they knew.”

For this lecture, he challenges his audience to look at Emilio Aguinaldo — “the hero we love to hate,” he quips — in a different light as he discusses the Philippine flag, the national anthem, and a narra table

Through a window

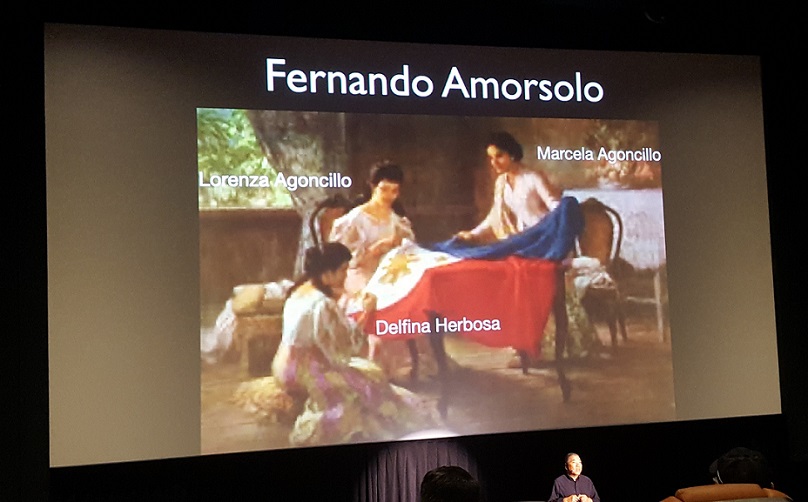

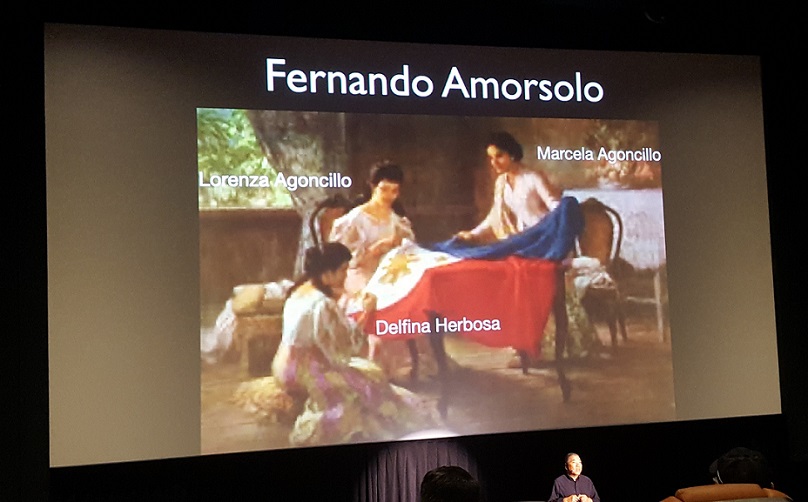

The Philippine flag was sewn and embroidered by the triumvirate of Lorenza Agoncillo, Marcela Agoncillo, and Delfina Herbosa, says Ocampo, a Horacio de la Costa professor in humanities and history at Ateneo de Manila University. Aguinaldo carried the flag with him from Hong Kong to the Philippines on board the USS McCulloch and first unfurled it in Alapan, Cavite, on May 28, 1898, after winning against Spanish troops.

Stories about the original flag’s whereabouts say that Aguinaldo had the flag. Ocampo rebuts this, saying Agoncillo’s flag was ceda (silk) and Aguinaldo’s was cotton. And no, Ocampo doesn’t know its current location.

Ocampo clarifies other points about the flag, saying: The white triangle is from a Katipunan flag; the three stars represent Luzon, Mindanao and Panay; and the sun’s rays do not represent the eight provinces that revolted against Spain.

“Manila, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Laguna, and Batangas were the provinces placed under martial law,” explains Ocampo.

Similarly, Ocampo corrects the conventional history lesson of Aguinaldo declaring Philippine independence from the balcony of his house in Kawit, Cavite. Ocampo’s photo of the house’s National Historical Commission marker shows a description in Tagalog stating that the declaration was read from a window facing a road.

The tragedy is not in the location’s inaccuracy, but that “declaring independence is one thing and winning it is another,” Ocampo says.

He adds, quoting Aguinaldo: “The United States merely returned the freedom we declared and won in 1898.”

True colors

Ocampo underscores a fact about the Philippine flag’s colors that, he says, no one wants to remember — that they are based on the American flag. It is stated in the Declaration of Independence, which, to Ocampo’s avowed disgust, had an impression of the National Library stamp at the margin when he got hold of the antique document.

An excerpt translated from Spanish into English reads: “…the colors red, white, and blue of the flag of the United States of North America as a manifestation of our profound gratitude to this great nation for the disinterested protection that she lends and continues to lend.”

Narrates Ocampo: Aguinaldo thought independence was in the bag, but his trusted adviser, Apolinario Mabini, thought otherwise and told him that the declaration was premature. Mabini then asked if Aguinaldo had it in writing, and Aguinaldo replied it was sealed with a handshake.

Mabini’s misgivings were proven right because the Philippine flag was prohibited from being exhibited until two laws legalized its display, Ocampo says. The first law was the 1920 Act 2928 that recognized Aguinaldo’s Katipunan flag of a yellow sun with its eight rays and five-point stars, white triangle, and the colors blue and red. The second was the 1936 Executive Order (EO) 23 standardizing the “…solid golden sunburst without any markings.”

Redesigning emblems

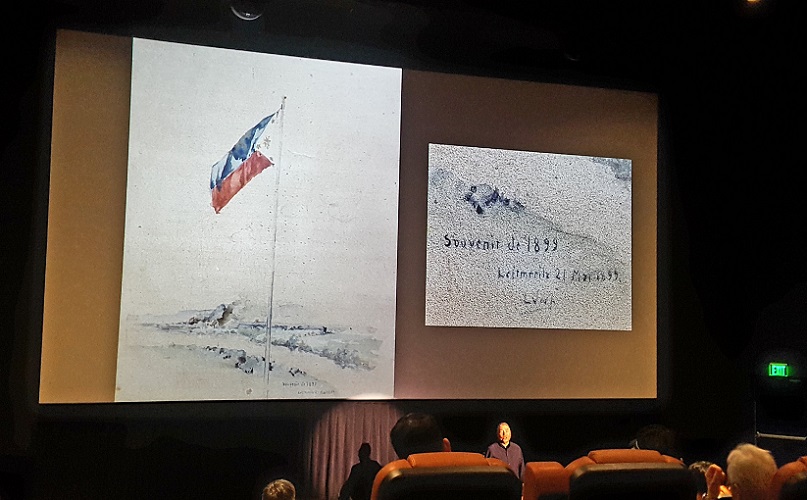

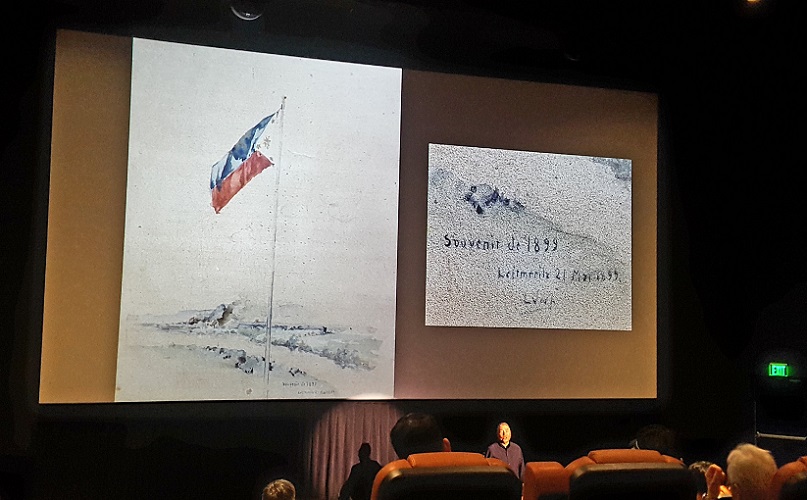

Then-President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. raised a stink on Feb. 25, 1985, about the colors: He declared that the shade of blue was historically inaccurate. He sought to restore the flag’s blue color to its “original” lighter shade with EO 1010, according to Ocampo, who helped solve the color debate with his serendipitous discovery of a bag of documents that he chanced upon in a research jaunt.

The documents were being sold for scrap at ₱3,000; he offered to buy the lot at ₱6,000, but was refused. Nonetheless, he retrieved Juan Luna’s watercolor sketch of the Philippine flag — and the light blue of the Philippine flag reverted to the darker shade in 1986.

The clamor for change didn’t end with color. Amendments like adding a ninth ray to symbolize Mindanao and a crescent moon to represent the Muslims were raised at the 1986 Constitutional Commission. Ocampo says he joined the bandwagon, flippantly suggesting that Benigno Aquino Jr.’s picture replace the sun.

Similarly, the seal of Manila was not left alone. Then-President Fidel V. Ramos had the lion and eagle removed, but Ocampo said he insisted they be put back because “they’re in the constitution.” The seal is a coat of arms with blue doors and windows, a half-lion. half-dolphin creature, and Castilla Leon given to the Philippines by King Philip II, says Ocampo.

He says elements of the seal are still found in San Miguel Corp.’s logo that has the first two and in the Bank of the Philippine Islands’ emblem that has the last.

Ocampo says he contested the origins of the half-lion, half-dolphin creature (aka the Merlion) in the popular logo of the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), arguing that it had already existed in Manila since 1596, compared to the STB logo launched in 1972. He says he was chastised and told that he had “no future in diplomatic relations.”

He says he also received flak for saying that a flaw in the 1987 Constitution enabled calls for changes to the flag and other official emblems. His detractors dubbed him “[Gloria] Macapagal-Arroyo’s weapon in having the constitution changed,” he says.

Band music

Ocampo relates that Aguinaldo wanted something better than “Himno de Balintawak” and so told Julian Felipe to compose an anthem when they first met on June 5, 1898. In six days, Felipe played “Marcha Nacional Filipina” for Aguinaldo eight times.

Given the quick turnaround, Ocampo wonders if Felipe was a plagiarist or simply a harried composer because, he says, quoting Felipe, “…the composition carries vague melodic reminisces of ‘Marcha Real Española’ as can be seen in the first few bars of the hymn.”

Undoubtedly, given the fast tempo, one’s first impression of the hymn is it’s band music. “It’s very spirited [that] it’s hard to sing,” says Ocampo, playing a recording by National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab. Curious at what Aguinaldo heard, Ocampo asked Cayabyab to play the original “piano version with trumpets [at] tempo di marcia.”

All is history, and the incidental music, as Ocampo calls Felipe’s hymn, became the Philippines’ anthem, with the lyrics added later, first in English then Filipino. Now consider Ocampo’s contrapuntal scenario: Filipinos would have been singing Julio Nakpil’s “Marangal na Dalit ng Katagalugan” if Andres Bonifacio had not been executed. (Nakpil was the second husband of Gregora de Jesús, Bonifacio’s second wife.)

Roosevelt’s table

Per Ocampo, Aguinaldo’s “bad guy” image dominates Philippine history for the following reasons: He made the wrong choices; he was not educated abroad; he was a college dropout and a mama’s boy. Having said that, Ocampo, who admits to not being an Aguinaldo fan, asks: “Would anyone have done better than the 29-year-old [general] who had fought Spain, was fighting the US, and deciding based on his limited capabilities?”

“History is about understanding, not judging,” he declares.

Interestingly, Ocampo’s story of Aguinaldo’s gift to former US president Franklin Roosevelt gives a positive spin to Aguinaldo’s tarnished reputation. Aguinaldo gave Roosevelt a polished narra table with a carabao head jutting out from underneath that continuously “gored” people.

According to Ocampo, Aguinaldo revered carabaos because they stopped the Americans from going after the Filipinos — i.e., getting between enemy forces and Filipinos and “[rushing] into [US] battery… [breaking] one man’s leg and [goring] several of the soldiers” in Meycauayan, Bulacan. He says the carabaos’ hatred of American soldiers stemmed from the animals’ dislike of blue khaki and of the Americans’ smell (being uncircumcised).

A new table from then-President Elpidio Quiring replaced the narra table after a reporter pointed out a crack in it during Quirino’s 1949 US state visit. Quirino promised one without a crack because the country was now a “solid one” unlike in Aguinaldo’s time, says Ocampo.

Quirino’s table with small carabao heads arrived in the United States on May 9, 1952. Aguinaldo’s table was shipped to the Smithsonian Institute where, laments Ocampo, it is categorized “un- located.”

Vulnerable general

Aguinaldo looked less than all-powerful in his later years. He entered politics and his relationship with Manuel L. Quezon went south. Ocampo says Quezon “[gathered] dirt” on Aguinaldo, whose dossier was replete with intel on his debts, properties, and hints of mishandling “the status of the Veterans Association’s funds.”

Ocampo conjectures that the general unfavorable view of Aguinaldo was all Quezon’s doing. “Would Aguinaldo have been seen differently if he didn’t run [for the presidency] against Quezon in 1935?” he asks his audience.

Aguinaldo looked even more vulnerable in a photograph that Ocampo shows of him waving a little Philippine flag while convalescing from his appendectomy at the Philippine General Hospital in 1920. (Subsequently, he had another surgery to remove a towel left inside by the surgeon, Ocampo says.)

Contributing to Aguinaldo’s pitiable state was learning of the cancellation of his pension granted by the Americans in 1920 on Jan 1, 1939. (Ocampo says it was restored.)

Viewing Aguinaldo from a different angle is not about deodorizing his image and his shortcomings. Historically, he went through with the execution of the Bonifacio brothers despite commuting their death sentence to banishment. He was swayed by Generals Mariano Noriel, Pio del Pilar, and Mamerto Natividad, Clemente Jose Zulueta, et al. to the idea that a living Bonifacio was detrimental to the revolution, wrote Teodoro A. Agoncillo in “The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan.”

Aguinaldo got the brunt of the opprobrium when he was not the sole antagonist in Philippine history, if one is to look at history with a scientist’s dispassionate eye. Ocampo says that Aguinaldo, who made decisions based on what he knew, surrounded himself with brilliant people whose advice he always followed. In fact, getting to Aguinaldo was difficult because people had to get past his wife, Ocampo says.

The roles of heroes and villains in history are not cast in stone. They change with every historical document discovered, allowing one to debunk/prove a hypothesis and correct a narration of an event and knowledge of a historical figure. It’s no different with Aguinaldo, whom Ocampo describes as a complicated man that outlived his enemies. (Similarly, Ocampo hints at re-learning about Mabini, the “sublime paralytic” who’s “different with and without power.”)

To end his lecture, emphasizing his call for an objective view of history, Ocampo says: “Is our view of Aguinaldo colored by politics? We must reconsider Aguinaldo and our history based on fact, not emotion.” #

Visit Lopez Museum and Library on Instagram (@lopez_muse) for their upcoming lecture series.