The Philippine-American war started on February 4, 1899 or 125 years ago — when Private William Walter Grayson fired the first shot. It’s a topic that the historian Ambeth Ocampo expounds on with aplomb. But, in prepping for his lecture “Breaking Up is Hard to Do: The Philippine-American War Revisited,” he admitted it wasn’t without challenge.

The difficulty was with the information available. Depending on the research terms one looked at, the number of materials varied. For example, “Philippine insurrection” showed more than 200 resource materials, and “Philippine-American war” only 16.

“History involves a paradigm shift,” Ocampo said in explaining the disparity. “The term ‘war’ means a fight between nations or states while ‘insurrection’ refers to a battle between people and government.” (Tellingly, the Americans saw the Philippine-American war as merely an insurrection.)

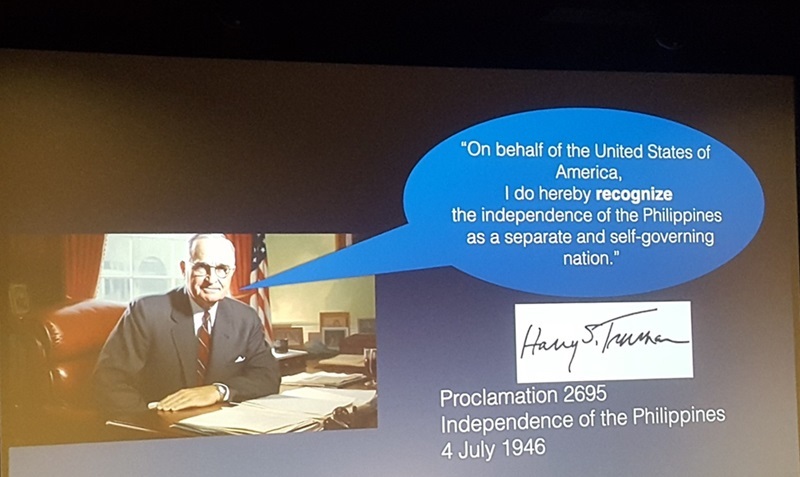

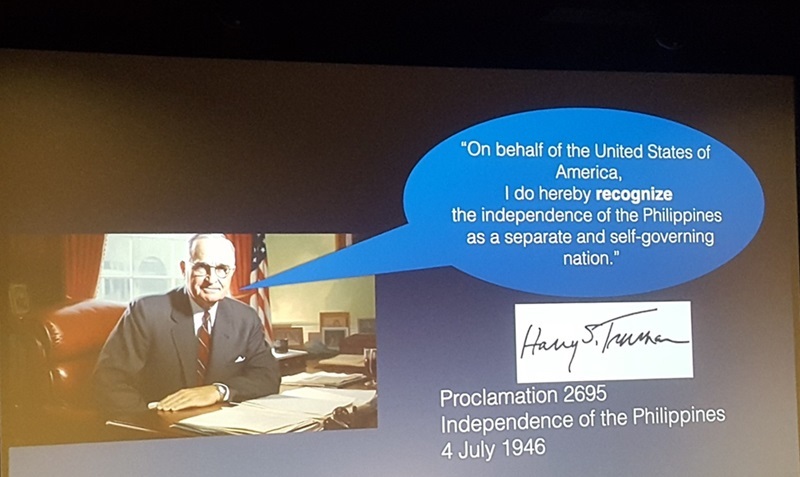

He also cited the semantics — i.e., the word “recognize” that US President Harry S. Truman used — pointing out that Truman “recognized the independence of the Philippines, but didn’t say our independence was given.”

Ocampo’s lecture last Feb. 3 at the Power Plant Mall Cinema in Makati City inaugurated the Lopez Museum and Library’s lecture series for 2024.

‘Useless information’

Updating his notes on the Spanish-American war and Philippine-American war, Ocampo led his audience to see the connection of the two wars to get the bigger picture while also laying down the context for understanding history and the historian’s work.

“With history, you have to sit down and notice. My friends said I should have been an anthropologist and not a historian because I look into details. I am a fountain of useless information,” he said, drawing laughter from the audience.

Compared to his colleagues who focus on detail and chronology, he’s “interested in the story, in finding [the] lost appreciation for useless information [because] the magic lies in the connection, not the data.”

So that morning’s history lesson began with information on a statue of a woman holding a wreath and trident at Union Square in San Francisco. The statue, he discovered, was a monument to Admiral Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay in 1898.

‘Hiding in plain sight’

Ocampo likes visiting places Jose Rizal had been to, such as The Palace Hotel in San Francisco, and the statue held no significance until much later. Rizal stayed in the hotel in 1888, paying US$4 for a room, wrote Ocampo in his book “Rizal without the Overcoat.” He added in his lecture that Rizal hated his American sojourn because he was detained by immigration authorities despite traveling first-class.

It was while waiting for a relative at Union Square that Ocampo looked at the statue, but he hardly noticed that Philippine “history was hiding in plain sight.” His experience illustrated what he saw as history’s quirkiness: “We see but do not notice.” Upon a closer look, the marker had a “snippet of how Dewey entered Manila, including Dewey’s famous line, ‘You may fire when you’re ready, Gridley’.”

To those unfamiliar with Philippine history, commemorating Dewey’s victory lends credibility to the idea that Filipinos were freed from their Spanish colonizers. But the devil is in the details. The monument, in fact, contrasted with Ocampo’s revelations of the realities behind the wars.

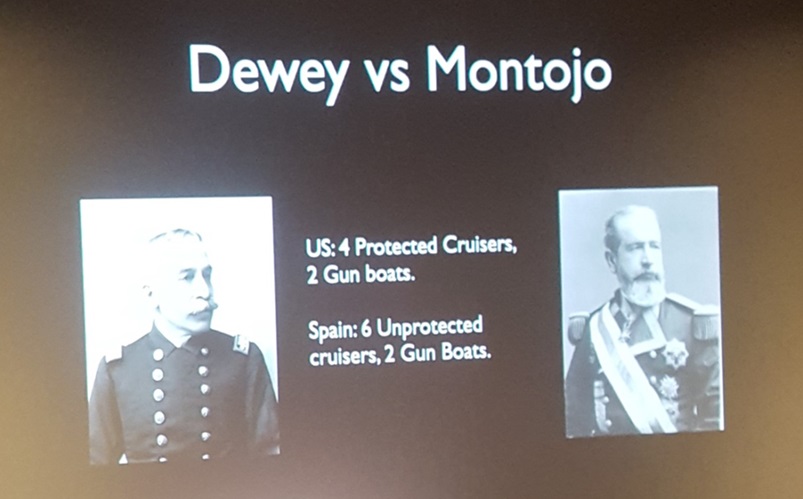

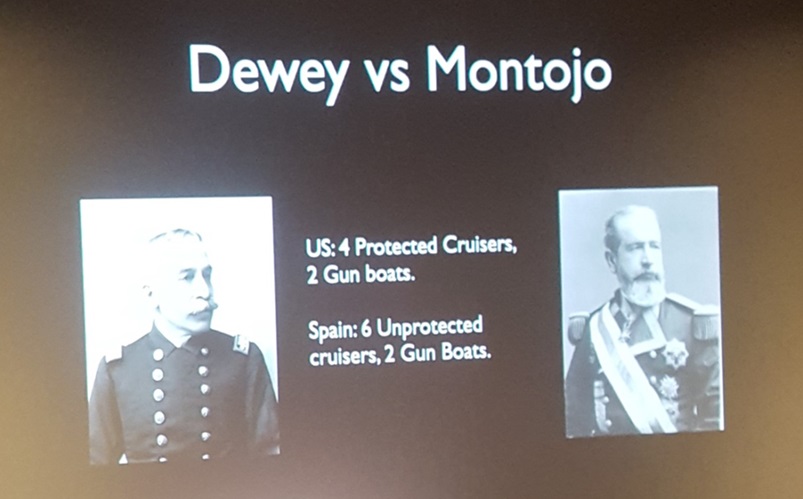

Factually, Spain and America declared war on Philippine soil on April 25, 1898. The Battle of Manila Bay commenced on May 1, 1898, and, in a trice, Dewey declared victory at Manila Bay over Patricio Montojo on May 2, 1898.

“Spain’s entire fleet sank, with 161 casualties and 210 wounded. [Dewey’s] ships had minimal damage, with nine wounded and one death due to heatstroke, explained Ocampo of his Keynote slide. “The Americans described the Spanish ships six unprotected cruisers and two gun boats — as ‘floating antiques’ because they were not protected by steel. The US had four protected cruisers and two gun boats.”

He added: “Spanish was surrendered to the Americans, not the Filipinos.”

All for show

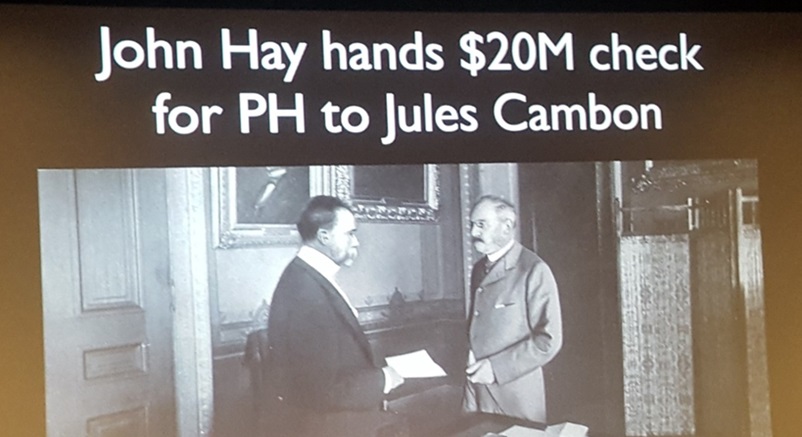

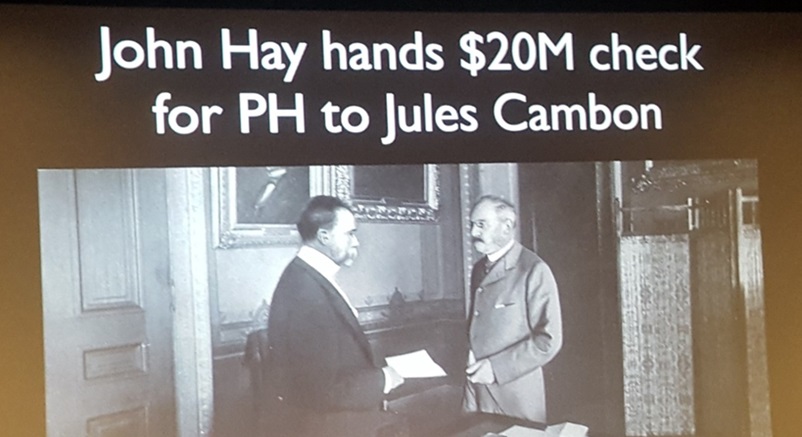

Philippine independence was never the goal. The agreement Spain and America signed behind the Filipinos’ backs ended the war, yet Manila was still colonized even without US reinforcements. While Spain walked away with US$20 million, America was king of the world. The ceding of the Philippines expanded America’s territory that already included Guam, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, and the Battle of Manila Bay went down as the greatest battle in US naval history, said Ocampo.

Consequently, Ocampo added, Dewey was hailed a hero whose obliteration of the entire Spanish fleet was prompted, not by a dedication to military duty, but because “he received a reward for each Spanish ship sunk.”

The mock battle at Fort San Antonio Abad on Aug. 13, 1898, further proved Spain’s abhorrence of Filipinos. Spain loathed the idea of surrendering to the natives, and Dewey provided a way for Spain to avoid it. He bombed the fort, ensuring Spain’s surrender to the Americans. Meanwhile, the aftermath of the Battle of Manila Bay indicated how the Philippines wasn’t important to America.

“[William McKinley] looked up the location on the globe, but could not have told where those darned islands were within 2,000 miles,” said Ocampo, quoting the then US president.

Manila Bay was surrounded by British, Dutch, French, German, and Japanese ships. Unwilling to yield particularly to the formidable pro-Spanish Germans — their fleet was bigger than that of the US — McKinley instructed the Peace Commission “to take Luzon and smaller islands around it on September 13, 1898.” But October 28, 1898, he wanted the entire archipelago.

Ocampo’s anecdote on Juan Luna and Felipe Agoncillo, who were part of the Peace Commission, highlighted the lamentable behavior of the ilustrado.

“They were under surveillance of the Americans who observed that Filipinos always woke up late,” Ocampo said.

‘Civilize them’

The basis of McKinley’s decision was, not equality, but his messianic view of America’s global role. He was compelled “to educate the Filipinos and uplift them and civilize and Christianize them….,” said Ocampo, quoting McKinley.

A wisecrack from Ocampo sent the audience laughing: “McKinley didn’t know we’ve been Catholic for 500 years!”

McKinley’s view was bolstered by author John Foreman and Gen. Arthur MacArthur Jr. from whom he sought advice. Foreman and MacArthur Jr. furthered the imperialist’s view. The former said Filipinos were uncivilized and incapable of self-governance while the latter saw “the archipelago [as) stepping stone to commanding influence: political, commercial, and military supremacy in the East.”

In reality, despite McKinley’s decision, the Americans weren’t sure what to do with the Philippines — a view echoed by US House Speaker Thomas Reed whose words Ocampo pulled up on screen: “We have bought 10 million Malays at $2 per head unpicked and nobody knows what will cost to pick them.”

Dangerous history

Ocampo’s insistence on historical accuracy isn’t a moot point. It’s the rationale of historical studies that has become political and dangerous for those advocating historical truth. An example is where Grayson actually fired the shot. Ocampo argued that it occurred in Santa Mesa, not on San Juan del Monte bridge, citing Dr. Benito Legarda’s report that didn’t mention any bridge.

Walking the talk, Ocampo, a former chair of the National Historical Institute (now National Historical Commission of the Philippines), had the historical marker in San Juan moved to the corner of Sociego/Silencio Santa Mesa in 2009. Pro-San Juan bridge advocates returned it to San Juan. Ocampo and his team countered by removing the marker at midnight and putting it back in Santa Mesa.

Thinking he was simply “doing history,” as he put it, Ocampo did not anticipate that correcting a historical inaccuracy would result in San Juan declaring him persona non grata and charging with theft and relocation of the marker.

Similarly, his assertion of Limasawa as the site of the first Easter mass versus Butuan, as others stubbornly declared, led to a petition filed against him in change.org for “peddling the Limasawa first mass hoax.” That got nowhere yet the Limasawa debate continues, to the detriment of other historians.

Ocampo said historians are afraid to do their work because they might get sued, as in the case of Resil Mojares. Per philstar.com, Mojares is facing a P20-million lawsuit filed in Butuan City by Potenciano Malvar, who accused him of “falsification and libel” for adopting historian Rolando Borringa’s finding that the first mass in the country was held at Limasawa.

Not to blame

Emilio Aguinaldo’s involvement in the Philippine-American war is another point of hairsplitting for Ocampo, who declared that Aguinaldo neither started it nor willingly turned over the country to America.

It’s no surprise that Aguinaldo always gets short shrift in Philippine history. After all, he had the brothers Andres and Procopio Bonifacio executed in the end. (He had decided to “commute their death sentence to banishment, but was dissuaded by Mariano Noriel et al., believing their story of Bonifacio wanting him dead and his position,” wrote Teodoro Agoncillo in “The Revolt of the Masses.”)

“Aguinaldo is the hero we love to hate. He went up North and the enemy couldn’t find him. When the first shot was fired, he was in Malolos hosting a ball,” said Ocampo. “Something got lost in translation. Grayson shouted ‘halt, which the Filipinos didn’t understand. In return, the Filipinos answered ‘halto’. The war was unintentional.”

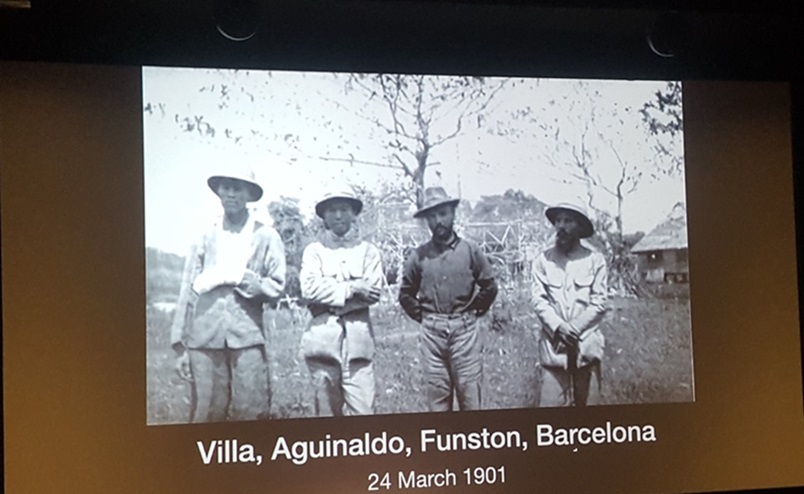

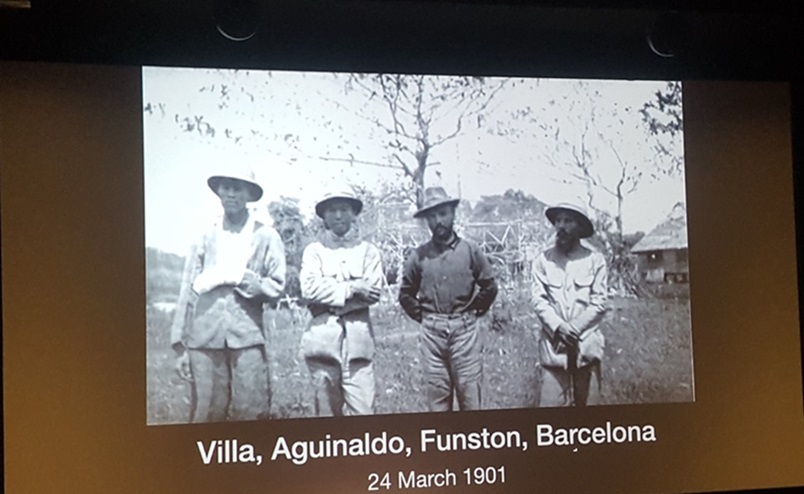

Aguinaldo was captured on March 24, 1901, at his headquarters in Palanan, Isabela, by Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston whose tombstone Ocampo saw while visiting Presidio with a friend. His friend needed to go to the bathroom and cheekily advised him to relieve himself on the tombstone.

“We need to take revenge,” Ocampo jokingly told the audience.

If one were to fault Aguinaldo, it was because, firstly, he didn’t have what Ocampo said was Apolinario Mabini’s legalistic mind. When the two met in Cavite at the declaration of independence that Aguinaldo led, Mabini asked him if he got the promise of independence in writing. Aguinaldo said the promise was sealed with a handshake.

Secondly, Aguinaldo lacked guerrilla warfare know-how: “If he’d used guerrilla warfare in the first phase we could have won the war, but he tried to fight a conventional war. They only used guerrilla warfare in the second phase.”

Grim heritage

Legacies are meant to be awe-inspiring and, thus, honored. But the “gifts” from the two wars are hardly reasons for Filipino to fête them except perhaps for the soup dish hototai. It was a culinary offshoot from “There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town tonight,” a favorite song of the American military during the Spanish-American war.

The torture “water cure” was another inheritance from the Spanish-American war. Ocampo said it was done with a military surgeon present who guaranteed that the victim experienced the worst pain without dying. In Ocampo’s writing about this and other atrocities of the Americans during the war, trolls came out questioning his integrity and labelling him a communist.

“The Spanish-American War started on humanitarian grounds to help Cuba — but it was an excuse for the US to flex its muscles,” explained Ocampo. “It led to the Philippine-American war and the US intervention in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The US…has always been looking elsewhere for intervention.”

Meanwhile, the legacy of the US$200-million Philippine-American war weighed grimly on the Filipinos. Per Ocampo’s Keynote slide on the staggering statistics: “took three years; 4,200 American casualties; 20,000 Filipino combatants dead; 200,000 Filipinos dead from violence, famine, and disease.”

“Love-hate relationship”

Despite the Americans treating the Philippines as an insular possession — they didn’t want to annex the country — and all the prejudiced underpinnings of their 45-year regime, there existed what Ocampo called a “strange love-hate relationship” between the two.

Comparatively, the Spanish rulers treated Filipinos abominably, regarding them as pariahs undeserving of freedom and rights. In contrast, the Americans were bonhomous especially towards the ilustrado “who weren’t given the chance to govern the country” during the Spanish time.

“The Americans gave [the ilustrado] limited power and created an upper class that oppressed 98 percent of the country,” said Ocampo.

Tongue in cheek, he added: “I tell my students in Ateneo that they’re the two percent who will oppress the 98 percent later.”

Were Filipinos better off under the Americans? “Part of the problem in the Philippines is the upper class oppressing the people that goes back to [the time of] Humabon. They’ve always collaborated with the superpowers. It’s not [stated] in our history but you will see it if you look at the details,” he declared.

New understanding

Historians face formidable tasks, said Ocampo. First, they must read the voluminous secondary journals available online to come to a new understanding of Philippine history. Next, Philippine history must be taught properly; it’s not memorization, as the popular impression goes.

“History is about teaching students to have, one, the ability to be critical [thinkers]; two, to develop an appreciation for “useless things”; and, three, to connect things,” Ocampo reminded the history teachers.

Naturally, before the teaching of Philippine history begins, textbooks must have factually correct details. “The interpretation will come later,” he said.

Visit @lopez_muse in Instagram for information on Ambeth Ocampo’s next lecture and other lectures.