August 30 has been declared by the United Nations as International Day for Victims of Enforced Disappearances.

We remember Primitivo Mijares, Fr. Rudy Romano, Leticia Ladlad, Nona Sta. Clara, Teddy Rabelista, Romeo Legaspi, Jimmy Malicdem, Jonas Burgos.

These are a few names of Filipino desaparecidos (the disappeared) across different administrations, from Ferdinand Marcos Sr. to Ferdinand Marcos Jr., whose fate remains in limbo. Their names are among the hundreds of victims of human rights violations during the darkest years of the tyrannical and rapacious Marcos Sr. regime engraved in the “Bantayog ng Mga Bayani,” or Monument of Heroes. Forever present in the hearts of their surviving loved ones, they are among the thousands of the world’s desaparecidos, whose memory the community of nations officially remembers today.

Truth remains to be revealed. Justice persists to be an elusive dream. Reparation echoes as an empty promise. Indeed, despite the existence of the Republic Act 10353 or the Anti-Enforced Disappearance Act of 2012 signed into law by the late president Benigno Aquino lll, the list of names continues to lengthen. After Marcos Sr. imposed martial law, the Philippines has miserably failed to concretize the elements of transitional justice i.e., truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence.

Regrettably, the democratic space gained after the downfall of the first Marcos administration in 1986 saw a serious failure to learn from the pivotal lessons of martial law. This included not thoroughly investigating instances of human rights abuses, neglecting to bring cases before the court, and holding the responsible parties accountable. Unresolved issues of poverty and social injustice, which are the root causes of dissent in a nation known for its enduring insurgency, continue to persist. Therefore, cases of human rights violations including enforced disappearances are doomed to be repeated.

As families of the victims’ demand truth and justice, their plea also includes a call to put an end to the list of suffering. Ironically, however, the list continues to lengthen. Under the present Ferdinand Marcos Jr’ administration’s watch, new names are being added to the litany of names.

Desaparecidos, a group of families of the disappeared under the umbrella organization, Karapatan, has listed new names of desaparecidos: Elgene Mungal and Ma. Elene Pampoza disappeared on 3 July 2022; Ariel Badian, disappeared on 7 February 2023, Renel de los Santos, Denald L. Mialen and Lyn Grace Marullinas, disappeared on 19 April 2023; Dexter Capuyan and Gene Roz Jamil De Jesus, disappeared on 28 April 2023.

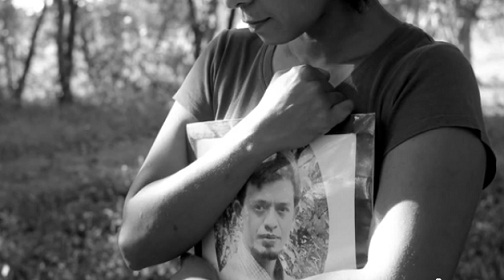

Melvin Rabelista is a sister of a desaparecido from Negros Occidental, Teddy Rabelista. When asked about the significance of the International Day for Victims of Enforced Disappearance, she lamented: “It is a day to remember our loved ones whose lives were plucked from the bosom of their families. It is a day for the renewal of our promise to search for them, to find the truth that will lead to the justice that they deserve. It is an important occasion to reflect on why this much-cherished justice remains elusive. We must examine our conscience on enforced disappearances persist in our supposedly civilized society.”

Despite national, regional, and global efforts to campaign and lobby for the ratification of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, the Philippines refused to sign and ratify the treaty, whose provisions have many things in common with its Republic Act 10353 or the Anti-Enforced Disappearance Act of 2012. The Philippine government’s refusal to ratify this fundamental international human rights treaty, which guarantees the right to truth and protection against enforced disappearances, can be attributed to a lack of political determination, concerns about international oversight and subsequent accountability, and a reluctance to fulfill reporting obligations.

Notwithstanding underreporting owing to many factors such as militarization, displacements, lack of access to national and international authorities, etc., the number of cases of the Philippines in the list of outstanding cases of the UNWGEID is 590 – the highest in Southeast Asia. While this is a national phenomenon in the Philippines, enforced disappearances are likewise a huge phenomenon in the Asian region, which, in the last two decades, many of the cases that the United Nations Working Group on Enforced Disappearances received come from. But it is the region with the lowest number of ratifications of the International Convention for the Protections of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Globally, according to its 2022 report, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UNWGEID) has forwarded a cumulative total of 59,600 cases to 112 different countries. The Working Group additionally indicates that the count of cases that remain actively under review, pending clarification, closure, or discontinuation, amounts to 46,751 cases originating from 97 individual states.

On this International Day for Victims of Enforced Disappearances, Amina Masood, wife of disappeared person and Chairperson of the Defence for Human Rights in Pakistan reflects: “The 30th of August always represents the struggle and the dedication of the victims’ families, who despite all odds, persevere and engage in various activities. They keep on raising voices for their disappeared loved ones. Being a wife of the disappeared for the last 18 years, amidst persecution, I always find it difficult to continue to fight and keep the flame burning, despite persecution. This day reminds me of my disappeared husband and the grand and small things we, along with our children, shared. This is an occasion for victims to sit in a quiet place, remember our loved ones who were and continue to be present in our hearts. They will never be forgotten.”

Enforced disappearances has reached global magnitude. In every nook and cranny of the world, people are not spared from this very cruel form of human rights violation where the uncertain loss creates a never-ending anxiety, a total absence of closure and a pain so profound that it never goes away.

Looking back to the origins of August 30, the Latin American Federation of Associations of Relatives of Disappeared-Detainees (FEDEFAM), in its founding Congress held in San Jose, Costa Rica in 1981, initiated to pay tribute to their disappeared loved ones by designating 30 August as the International Day of the Disappeared. According to Ma. Adela Antokoletz, member of Argentina’s famous Madres de Plaza de Mayo-Linea Fundadora, this date was originally meant to pay tribute to a disappeared Latin American woman. Antokoletz stated: “A single human being represents the whole humanity; thus, August 30 represents humanity.” As enforced disappearances spread globally, this day was adopted by similar formations of families of the disappeared across the globe.

Three decades later, the United Nations officially recognized the 30th of August as the International Day for Victims of Enforced Disappearances in 2011. This universal recognition signifies victory of the struggle of the families of the disappeared and the rest of the international community in their tireless insistence of the imperative of truth, justice, reparation, memory and guarantees of non-recurrence.

In March this year, I visited Argentina, a nation haunted by a grim history of enforced disappearances that unfolded during the era of military dictatorship in the 1970s. Leading the former Executive Committee of the International Coalition Against Enforced Disappearances (ICAED), I participated in the Third World Forum for Human Rights attended by 10,000 civil society organizations across the globe. As a side endeavor, we paid a solemn visit to the Parque de la Memoria, where a massive wall bears the names of 30,000 victims who suffered enforced disappearances. Adjacent to this wall of remembrance, a heartbreaking testament to cruelty, women were heartlessly thrown from helicopters into the ocean immediately after having given birth to their babies and fed them with colostrum, their fates forever sealed in the depths. Their children were also made to disappear, sold to childless couples in various parts of the world.

The thousands of desaparecidos (the disappeared) in Argentina are but a microcosm of the almost innumerable victims of enforced disappearances in the world, a small but poignant representation of the countless victims of enforced disappearances across the globe.

Asked about the significance of this day, Antokoletz, who was recently elected as the new president of The International Coalition against Enforced Disappearances (ICAED) shared: “It is a day of unity between families’ associations and the international community. It is annually celebrated with multiple activities, statements, posters, flyers which aim to reach communities victimized by this malady. This day aims to form more groups and federations that will amplify the voices of truth and justice.”

Geographically distant and diverse in culture, religion and language, organizations of the disappeared the world over are united in the same pain, in the same struggle, in the same hope and the same envisioned victory for a world without disappeared persons.

On 24 March, to honor those killed and disappeared during the “Dirty War,” Argentinian civil society organizations chanted: “Madres de la Plaza, el pueblo las abraza.” (Mothers of the Plaza, the people embrace you).”

The call for solidarity should resound across every corner of the globe, echoing the steadfast endeavors of empowered survivors and the enduring fight of empowered victims. Taking inspiration from the Argentinian women stands as a profound tribute and a potent homage to all the disappeared individuals worldwide.

Never Again!