Written by Dr. Binoy Kampmark

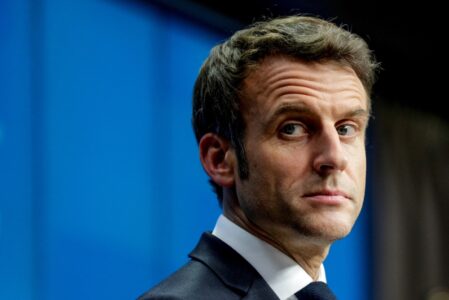

Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit to China did not quite go according to plan, though much depends on what was planned to begin with. In one sense, the French President was consistent, riding the hobbyhorse of Europe’s strategic autonomy, one hived off from the US imperium and free of Chinese influence.

Europe’s third-way autonomy would be a mighty thing for the Elysée Palace, especially given French pretensions in steering it. After all, Frau “Mutti” Merkel is no longer de facto European chief, presiding over the bloc with matronly care. Her successor, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, is finding himself caught in undergrowth, a difficult thing at times for the continent’s largest economy, and the globe’s fourth.

What, then, of the fuss? In the first place, Macron had company on his Beijing visit: on his first day of the trip, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had decided to come along. This was never going to go well, given their respective views over the Middle Kingdom. Von der Leyen, for one, uses a larded management approach to Beijing, ringing the relationship with restrictions and signals of constipation. On Taiwan’s status, she sticks to the warring line embraced by policy makers stretching from Canberra to Washington. Macron, at least in one sense, understands the power of China to be not only inextinguishable but a logical weight against the US.

The fuss then began in earnest with Macron’s remarks, made on his plane, the Cotam Unité, after the three-day visit. To reporters from Politico and Les Echos, he began conventionally, reiterating the view that Europe should be a third power, a counterweight to Washington and Beijing. But it was his remarks on Taiwan that caused some bristling across a number of quarters. “Do we [Europeans],” he posed to Les Echos, “have an interest in speeding up on the subject of Taiwan? No. The worst of things would be to think that we Europeans must be followers on this subject and adapt ourselves to an American rhythm and a Chinese overreaction.”

The mania over Taiwan’s fate constituted a potential “trap for Europe”, landing it in crises “that are not ours”. The heating up of the US-Sino conflict would frustrate European ambitions, be it in terms of time or finance, to develop “our own strategic autonomy and we will become vassals, whereas we could become the third pole [in the world order] if we have a few years to develop this”.

Those familiar with the Macron recipe have seen it before. An interview of frankness acts as kindling. The fire rages. Then come the explainers, clarifications, points of qualification. The fire abates. In 2019, he warned of NATO’s “brain death”. (Since then, that brain-dead patient has become ever more emboldened and enlarged, engaged in a proxy war with Russia.) He has also been unabashed about offering a fig leaf or two to Moscow, despite its Ukrainian adventurism.

Representatives of the US empire-set, nervously clinging to orb, sceptre, and some misguided sense of civilisation, sneered and scoffed. Senator Todd Young (R-Ind.), rolling around in the rhetoric of anti-Sino thrill, called the Chinese Communist Party “the most significant challenge to Western society, our economic security, and our way of life”. The remarks from Macron had been “embarrassing”, “disgraceful”, and “very geopolitically naïve.”

Republican Florida Senator Marco Rubio, who sits on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, offered his few cents worth. “If Macron is speaking for all of Europe, and their position now is they’re not going to pick sides between the US and China over Taiwan, maybe then we should not be taking sides either.” His point: the US was essentially funding a European war, and to what end?

The Washington Post viewed the visit as one that “angered politicians and analysts on both sides of the Atlantic, highlighting gaps between the US and French approaches to China, showcasing division within the European Union – and probably delighting Beijing.”

The Wall Street Journal was even more bullish in its criticism, suggesting that Macron had refused to get with the anti-China deterrence program. (Good of the paper to openly admit that such a policy is actively being pursued in Washington.) “If President Biden is awake, he ought to call Mr Macron and ask if he’s trying to re-elect Donald Trump.” At the WSJ, warmongering is ascendant.

For some commentators, notably in Macron’s camp, the anti-China pugilists had misunderstood the whole message. This was the reading from French lawmaker Benjamin Haddad: “Macron is much closer to the European centre of gravity on China than the numerous scandalized comments on his comments would suggest.”

Chances are that Macron knew exactly what he was saying, cognisant of the preening egos he would affront. The same cannot be said about the number of US lawmakers who, ignorant of their own republic and its warring ambitions, are keen to interpret the views and ambitions of another as disturbingly independent of their own.

Were these figures to go back to school, directed by the spirit of Lafayette, and the French purse that was broken in supporting the American War of Independence, such lawmakers might show a greater appreciation about the view from Paris. But those days are long gone, and Washington, in its increasingly trembling way, is keen to stay the pretensions of any power that will challenge it, and make others toe the line.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He currently lectures at RMIT University. Email: [email protected]