When journalists first heard about the Bongbong rockets in March 1972, they thought it was just another government scam. As retold by the journalist Lee Lescaze, then President Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s press secretary Francisco “Kit” Tatad made this announcement to the Malacañang press corps:

“We have launched successfully our first rocket.”

“What is it this time?” a newsman asked. “We have had many rackets before.”

“It is not a racket but a rocket.” Tatad said.

Fifty-two years later, a new racket on the rocket is on the rise again.

Continuing territorial tensions with China have spurred the re-circulation of claims about the rocket development program under Marcos Sr. Encountering material on the Bongbong rockets is not that difficult. Besides the usual pro-Marcos YouTube videos (including this, uploaded on May 30, 2024, with over 23,000 views as of this writing), Marcos supporter tweets, and videos sharing Senator Imee Marcos’s half-truths about her father’s Self-Reliance Defense Posture (SRDP) program (such as this, uploaded in June 3, and shared over 560 times), one can find a recently opened permanent exhibit extolling the Bongbong rocket program, which is much more accessible than the rocket on display at the Philippine Navy Museum in Cavite.

On January 30, 2024, the 4th Marine “Makusug” Brigade inaugurated the Military Park in Camp Cape Bojeador in Burgos, Ilocos Norte. A Daily Tribune article noted that by March 7, 2024, the “military tourism” park had already received over 21,000 visitors. A May 6, 2024 ABS-CBN Facebook post showed that the attraction continued to be well-patronized. Located near the national highway, one can pass by the Military Park on the way up to visit other popular tourist destinations: the Cape Bojeador Lighthouse, the Burgos and Bangui Windmills, and the Patapat Viaduct. It is already in the itineraries of several Ilocos Norte tour organizers.

Pictures of the Inauguration of the Military Park in Camp Cape Bojeador, Burgos Ilocos Norte, from the Facebook page of the 4th Marine Brigade.

Based on the Facebook posts of some of the park visitors, one of the exhibits there is a replica of a Bongbong rocket launch vehicle. Part of the exhibit description reads:

This exhibit showcases a replica of a rocket integral to the Philippine military’s venture into developing its ballistic missiles. The initiative unfolded through the collaborative efforts of Filipino and German engineers and scientists, in partnership with the Philippine Navy under Project Santa Barbara of the Self-Reliance Defense Posture (SRDP) program in the 1970s. The rocket earned its moniker, “Bongbong Rocket” in honor of the then President Ferdinand E. Marcos’ son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos Jr, the 17th President of the Republic of the Philippines . . . Despite the promising advancements, the project was discontinued totally in 1986. Nevertheless, the innovative spirit that fueled this endeavor lives on. And the project’s enduring legacy stands as a testament to its positive impact on the Philippine military’s capability for technological advancements and scientific explorations.

Why project was named Sta. Barbara

The text calls the first launch “successful” and “triumphant.” SRDP proponents like Imee and Senator Bato de la Rosa say pretty much the same thing. Many have already attempted to explain—briefly, in fact-check format—how the country’s homegrown missile program was hardly the first within the region or was a resounding success. Most online articles state that the missile program was codenamed “Project Sta. Barbara”—patron saint of artillerymen.

launch tests were conducted in the 1970s; and the program, for unclear reasons, was discontinued. Some writers simply state that the discontinuance was a mystery or that the project’s details remain classified. Sources partial to the Marcoses claim or allude, like the Burgos exhibit text, that the project only ended after the fall of the Marcos regime in February 1986.

Bob Couttie, a historian, wrote a detailed description of the project, using declassified US Department of State cables among his primary sources. His blog post “Marcos’s Roman Candle Superweapons,” a version of which also appears as a chapter in his last book Fool’s Gold, largely tackles the entirely false claim that the Marcos regime successfully developed “anti-typhoon” rockets, before detailing why Project Sta. Barbara never produced what could be legitimately referred to as “ballistic missiles”: lack of funding, as well as the absence of support from the country’s eternal ally, the United States. But Couttie was unable to fill in a number of blanks regarding the rocket program using his sources: Who were the scientists involved? How many tests have extant documentation? How far in terms of technological advancement did the program reach? Did it really end because of Cory Aquino?

Most of these can now be better answered using recently accessible primary sources, some of which were marked “classified” or “secret” decades ago.

The president’s rocket men

If his February 13, 1971 diary entry were to be believed, Marcos Sr. was not even keen on having a missile system. The Israelis were hawking their Gabriel weapons system then. Marcos Sr. was thinking of something else.

“Saw the Israeli film on the demonstration of their Gabriel weapons system . . . what we really need is not a missile system for the Navy but airfields for our jet fighters in Zamboanga, Davao, Cagayan de Oro and Laoag and Legaspi in Luzon. Our fighters are now armed with missiles,” Bongbong’s father said.

Nine months later, he changed his mind. Marcos-supported rocket research appears to have started on November 21, 1971. On that date, Marcos met with a foreign physicist, Dr. Max Goldberger, to discuss the latter’s proposal for “catalytic research.” Also in attendance were National Science Development Board (NSDB) chairman Florencio A. Medina, a retired brigadier general of the Philippine Army. According to a confidential report written by Medina, transmitted to Marcos on December 4, 1971, further discussions with Goldberger were held with other government officials, including other persons from the NSDB and Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor. It was Melchor, a US Naval Academy graduate, who suggested that a “production laboratory” for the implementation of Dr. Goldberger’s proposal could be set up in “one of the vacant hangars at Sangley Point,” while the “machine shops of the Philippine Navy at Cavite City” could be one of the “supporting facilities for tooling.” Goldberger found these facilities to be adequate.

Florencio Medina’s Report on Dr. Max Goldberger’s Proposal for Catalytic Research by Verafiles Newsroom on Scribd

Florencio Medina’s Report on Dr. Max Goldberger’s Proposal for Catalytic Research, from the digitized PCGG files.

By the time Goldberger first met Marcos, he was listed as an inventor in a number of patents or patent applications assigned to Pioneer Research, Inc.” A news article in the February 1970 issue of the Manchester [Connecticut] Evening Herald describes Goldberger as the director of research and company vice president of Pioneer, which had developed a 100-watt commercial model of a hydrazine fuel cell. Goldberger also made the news in the 1960s for his propulsion experiments. One news article, from the Associated Press, talks about a November 1965 attempt by Goldberger to launch a rocket in Long Island, Connecticut. Goldberger and his team initially thought there was an “ignition failure,” but as they were packing up, “someone accidentally tripped the faulty ignition and the rocket shot 500 feet up,” which made Goldberger say that the “rocket’s performance…was a ‘ballistic success.’”

In the cover letter of his December 1971 report, Medina recommended pushing through with Goldberger’s proposal, committing the NSDB to collaborate closely with the foreign scientist. Medina said that the proposed program “is a laudible [sic] undertaking as it will introduce into the country at very minimal cost the basic techniques of rocket propulsion and of fuel cells which have paramount impact in both their civilian and military applications.” He stated that the initial expenditure may be USD 10-20 thousand, or PHP 66-132 thousand, or slightly more than 1-2 years of the president’s salary. Medina also emphasized that Goldberger offered his services “free of charge.” Marcos immediately approved the proposal.

Before publicizing their rocket research, the Marcos government first informed the United States of their missile plans. On December 13, 1971, Gen. Manuel Yan, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, gave a presentation on “The Attainment of a Self-Reliant Defense Posture” during the 71-12 Mutual Defense Board Meeting at Camp Aguinaldo. Among those in attendance were Marcos, US Ambassador Henry Byroade, foreign affairs secretary Carlos P. Romulo, and US Admiral John S. McCain Jr. In his speech, which gave a “detailed presentation of our plan to attain [a self-reliant defense] posture with the assistance from our allies, particularly the United States,” Yan said,

The importance of an indigenous capability to produce explosives and propellants may not readily be apparent . . . But the other important objective is the development of rockets and missiles . . . In essence, mastery in the production of explosives and propellants is the key to the attainment of a strategic power of deterrence.

In his diary entry for December 14, 1971, Marcos Sr. wrote that he “ordered the rocket research and experiments of Dr. Max Goldberger to be started.” Marcos Sr., also said that he will “fund [the research] with the Intelligence Funds at [his] disposal.” Unverifiable claims would later be made that the rockets were funded with money from the Marcos Foundation, where he falsely claimed to have deposited all of his wealth.

Marcos Sr., in his diary entry for December 28, 1971, mentioned that he had dinner with Goldberger, congressman Antonio Raquiza, and an Alex Rothchild. He noted that Goldberger was “married to an Ilocana niece” of Raquiza, a close Marcos ally, which may account for Goldberger’s initial access to Marcos.

Bongbong rocket lift-offs—and letdowns

The first known rocket launch took place on March 12, 1972. The Burgos exhibit text echoes some of the reportage on that launch, including Melchor’s claim that the Bongbong rocket was built in only twenty-one days. If that is factual, then construction of the rocket would have started in late February 1972, or more than two months after Marcos approved the Medina-endorsed Goldberger proposal. Based on his diaries, Marcos met with Goldberger on February 12, 1972, “for our experiments and research on guided missiles and chemically powered batteries.”

What was launched in March 1972 was called “Bongbong II”; it is unclear what happened to Bongbong I, if there was one. Reports about the launch that were released soon after it took place include one from UPI, which stated that, based on Malacanang sources, “the Philippines has successfully launched its first home-made rocket secretly.” It also stated that Marcos had shown his cabinet “a 30-minute film of the launching from Caballo Island near Corregidor Island at the mouth of Manila Bay and the rocket being retrieved by the Armed Forces in the South China Sea.”

The article by Lee Lescaze on the launch, which quoted Tatad’s exchanges with the press, was well syndicated in US newspapers such as the Los Angeles Times. It was published between August-September 1972—several months after Bongbong II lifted off. The article included numerous details about the launch and Bongbong II itself—purportedly, it cost “only” USD 3,250.00 (about PHP 22,000.00), was eight feet long and six inches in diameter, and was hand-fed into a launcher made from “a piece of pipe found in a junkyard in Manila’s Chinatown.”

Marcos supposedly flew to Caballo to witness the launch, even after he was told that the chance of success was only 60 percent. It did seem that the launch was going to fail; reminiscent of Goldberger’s 1965 test in Connecticut, Lescaze said, “The range officer began his countdown, but at zero, Bong-Bong II remained on the pad. Flustered, he began counting and at ‘two,’ the rocket took off.”

Lescaze’s article quotes Melchor several times; the executive secretary was referred to as the “father of the Philippine rocket program.” Goldberger is not mentioned in the article at all. Interestingly—and not entirely in agreement with accessible primary sources—the article claimed that the project was “the result of a secret crash program by a group of Filipino scientists who had set out to design a windmill and then realized they had a rocket within their grasp.” Toward its conclusion, the article noted that “the missile budget has been cut in half as part of government austerity efforts following July’s disastrous flooding of central Luzon. Tests are continuing at Caballo, however.”

On November 18, 1972, Melchor asked for clearance to launch another liquid-propellant rocket, Bongbong III, on December 2 that year. Besides “maintaining the momentum” of the rocket project, Melchor also hoped that the test would help them explore the “possible rain-making application of the rockets,” i.e., sending up a “vehicle which will carry a payload of silver iodide to a desired altitude,” and to “acquire experience in the use of hydrazine,” “the ultimate in rocket fuel,” and to “get a feel of firing a more sophisticated and bigger rocket.” Melchor noted that “With the present control of government over media”—this was, after all, almost two months after the start of the Marcos dictatorship—”the test can be conducted with the least of fanfare, treating it just like any routine scientific and technological test.”

Epic fail

The launch failed spectacularly. Marcos wrote in his diary on December 3, 1972, “Bongbong III (the 180 mm hydrazine fueled rocket) exploded on take off at the test site in Caballo.” The report attached to the diary entry noted that “The explosion scattered the various missile components in the launching pad and buckled and broke open the seams of the heavy steel gate separating the launching pad from mission control.” The report was signed by Commodore Alfredo C. Protacio of the Philippine Navy and E.M. Terrado (“Head, Chemical Grp.”), both of Project Sta. Barbara. Throughout the rest of its existence, Project Sta. Barbara was directly under the Office of the President.

A June 1, 2024 Facebook post of the Naval Research and Technology Development Center states that their institution was established “in pursuit of fortifying the country’s Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) Program, specifically the Project Sta. Barbara” in 1973. An article co-authored by Terrado in the June 1974 issue of the Philippine Journal of Science discusses fuel cell research being done at the Sta. Barbara laboratories. It is thus safe to say that part of Sta. Barbara’s funds, which were not exclusively for rockets, came from the Philippine Navy.

A more successful launch was conducted on December 30, 1972, the hundredth day since the official date of Marcos’s martial law declaration. The day before, Melchor sent a message informing Marcos that he and Secretary of National Defense Juan Ponce Enrile would be at Caballo for a missile test. After the test, Melchor sent a dispatch to Marcos’s presidential yacht to say that the launch of the “Bongbong 7” was successful, and that he would like the yacht to pass by Caballo so that they can salute the president. Unfortunately, the message was not received on time—the yacht was already at Sangley Point—so no post-launch salute “on the occasion of the one hundredth day anniversary of the New Society and [Marcos’s] seventh year as president” took place.

Dispatches on the Launch of Bongbong 7 by Verafiles Newsroom on Scribd

Dispatches on the launch of Bongbong 7, from the digitized PCGG files.

Further tests were conducted in 1973. Marcos’s May 13, 1973 diary entry states that “Our missile tests have been successful and we have a launcher on a dump truck that can be pivoted on a 360 degree and elevated up to vertical.” Several pictures of the tests conducted the day before were attached. The pictures show the launcher, called “Bukang Liwayway,” which was further labeled “SP [solid propellant] Missile Launcher” and “Missile Defense Command.”

Marcos claimed in his diary entry that the missiles showed up in the radar scopes of the helicopter and planes at the US Air Force base in Clark, Pampanga. A photo in the set shows Marcos with Melchor and Goldberger. It is unclear how many rockets were tested, but the launcher had six barrels.

Photos of the May 1973 rocket tests, from the digitized PCGG files.

Neither the December 1972 nor the May 1973 launches are known to have been covered by the international media. What appeared to be the Bukang Liwayway launcher, carrying six Bongbong rockets, was rolled out in the 1973 Independence Day Parade in Luneta, about a month after the May 1973 tests. Instead of Bukang Liwayway, however, the label on the launcher said “WX Modification & Research”—a reference to the program’s weather manipulation aims (WX has been an abbreviation for weather since the morse code/teletype era). Couttie explained that by the early 1970s, researchers in the US—where silver iodide weather modification experiments started in the 1940s—were already very skeptical of the efficacy of dropping or launching chemicals into clouds to weaken hurricanes.

U.S. assessment of Bongbong rocket project: overly expensive, wasteful

A declassified confidential cable from the US Department of State, dated February 6, 1974 concerns an aide memoire from Melchor about a standing request for assistance in the Philippine rocket research program, first made in October 1973. Melchor stated that the program would be a “heavy burden” on the “finances of the [Philippine] economy,” and rocket development thus far had “been met with early technical reverses primarily due to the absence of the much needed logistics support base”; he emphasized that “The critical lack of experience and a working model proved very costly and has drained heavily the meager resources appropriated for [the] endeavor.” Melchor noted that what they wanted to build was a multipurpose rocket, both for defense and for sparing the Philippines from “yearly destructions caused by the extremes of weather.”

The US ambassador, William Sullivan, recommended “modest assistance in technical package with training and advice as well as models,” but no accessible records show that any such assistance was given. US National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger believed such assistance would be going down a slippery slope: “We saw no particular problems in giving Melchor ‘exces’ Nikes [Nike-Hercules missile ‘cadavers’] as tinker toys,” but “Our feeling is that any meaningful assistance to the Philippine missile program would be overly expensive, wasteful of Philippine resources and unhelpful to the Philippines or to the USA.” In a July 3, 1974 cable, Sullivan tried to argue to give Melchor his missile cadavers, to no avail.

The next launches that made the news abroad were done in September 1975. Government issuances on the tests were, expectedly, brimming with praise. According to the September 5-11, 1975 “Official Week in Review,” on September 7, Marcos “announced that the Philippines is engaged in an experiment in the local production of ballistic missiles in pursuance to its Self-Reliance Defense Program”; “The defense of the Philippines cannot be left to alliances with other countries,” the President said as he witnessed the successful test-firing of locally produced missiles at the northern coast of Luzon….Dubbed the ‘Bongbong’ rockets, the missiles were fired some 10 to 12 kilometers into the sea from launchers mounted on a military vehicle parked along the shoreline.” A declassified US cable states that, as per Manila (government-controlled) press accounts, the rockets “went ‘roaring two kilometers into the sky.’”

An Associated Press article published in US newspapers, relying solely on Philippine government sources, said that four rockets were launched, and that the tests were witnessed by Ferdinand, Imelda Marcos, and “the couple’s two children”—possibly Irene and Bongbong, who had yet to start his failed pursuit of a bachelor’s degree in Oxford.

Americans, or at least Ambassador Sullivan, were not impressed. In a confidential cable dated September 18, 1975, the man who had overseen a secret massive bombing campaign in Laos said, “This latest launch event suggests that the local state of the art is still not much beyond the Roman candle stage (photos show no evidence of any associated guidance or other electronic gear), and that ‘our own ballistic missile’ is still on the drawing pad.”

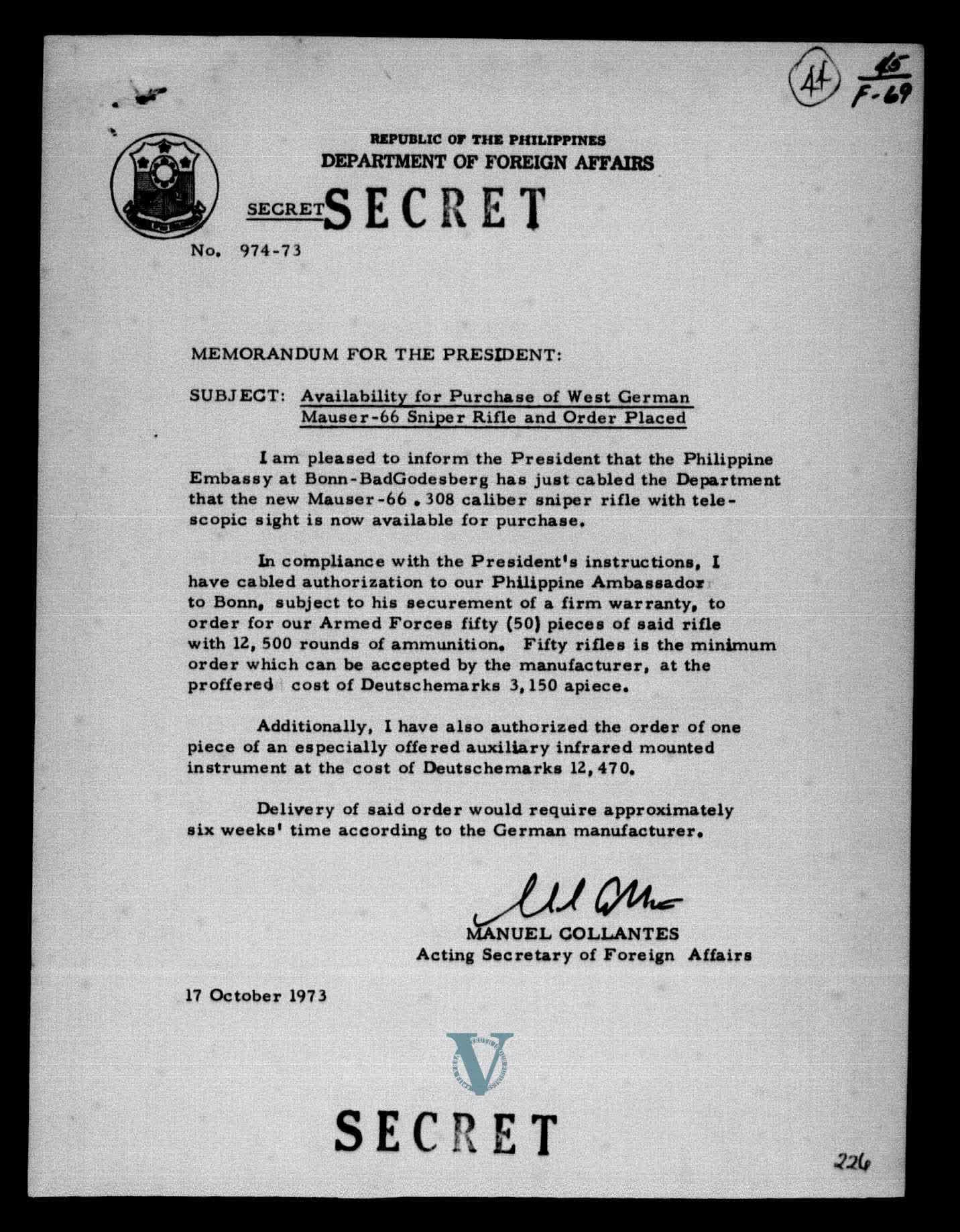

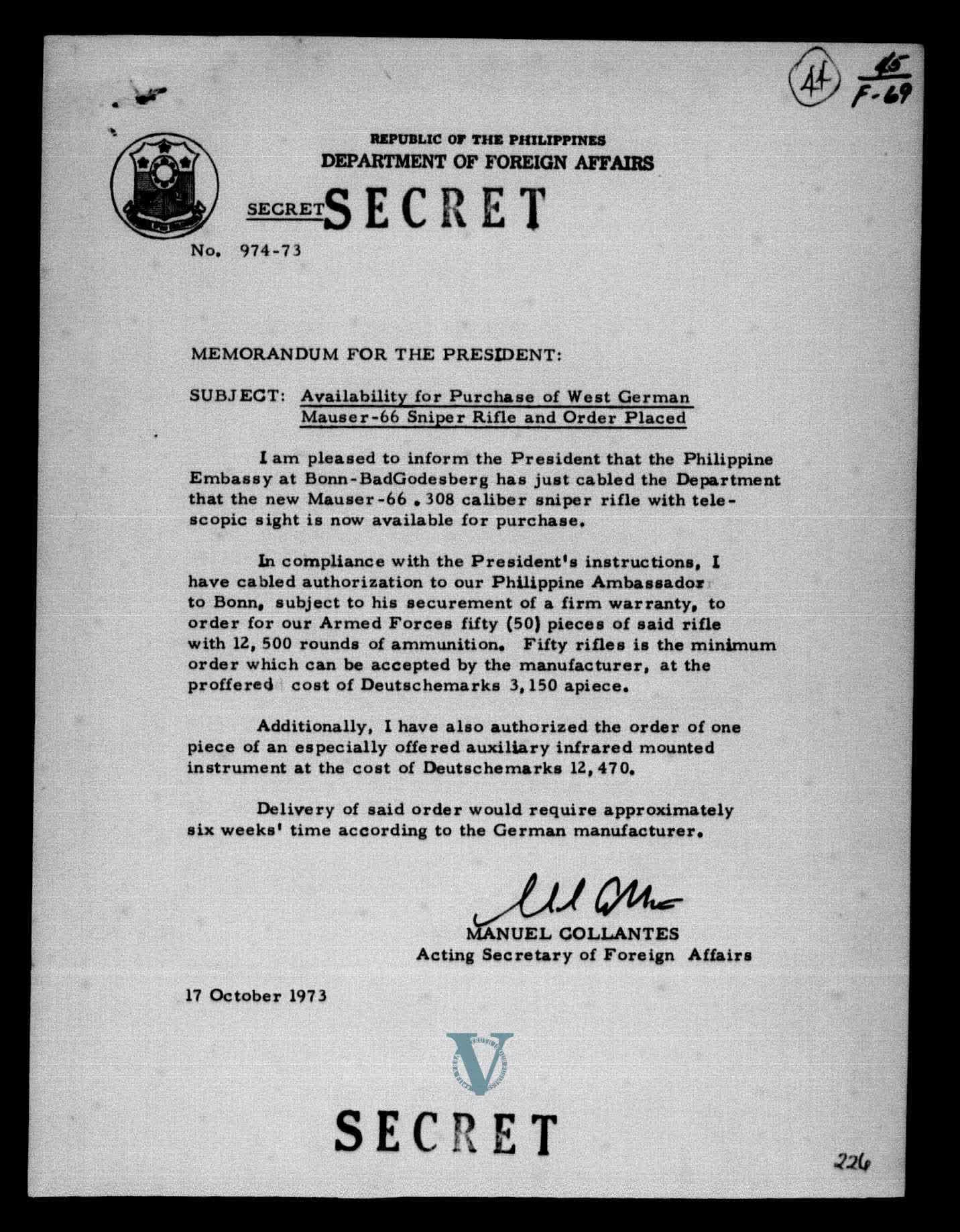

Yet even as Marcos and his gang tried to inveigle American aid for a key component of his SRDP, in secret, he appeared to be wasting the country’s scarce foreign reserves—one of the very resources that SRDP was trying not to waste—to indulge his desire for sniper rifles.

Manuel Collantes, then acting secretary of foreign affairs, sent a memo to Marcos on October 17, 1973, that they can by then purchase from West Germany “Mauser-66 .308 sniper rifle with telescopic sight.” Marcos ordered “fifty (50) pieces of said rifle with 12, 500 rounds of ammunition . . . at the proffered cost of Deutschemarks 3,150 apiece.” With that bundle came “one piece of an especially offered auxiliary infrared mounted instruments at the cost of Deutschemarks 12, 470.” A piece fit for a despot or a king.

Bye Bye Sta. Barbara

Andrew L. Ross, in a chapter of the 1984 book Arms Production in Developing Countries, noted that “the Philippines has not developed or produced guided missiles,” but, based on the September 1975 tests, the country “has reportedly designed an artillery rocket.” “Subsequent developments” after the 1975 launches “have not been revealed,” Ross continued. In a footnote, he further added, “AFP Officers were not eager to discuss the Bongbong rocket and little is publicly known about the project.”

Indeed, there were no further reported developments on the rocket program after 1975.

Incidentally, Melchor was replaced as executive secretary in November 1974, and the office of the executive secretary was replaced by various presidential assistants beginning in December 1975. Bongbong (the person) would himself be appointed “Special Assistant to the President” in 1978. In his memoir Endless Journey, Jose T. Almonte claimed that Imelda Marcos distrusted Melchor, alleging that he was “involved in a plot to overthrow” Marcos. Melchor continued to have Marcos’s ear, however, being appointed a board member of the Development Bank of the Philippines and becoming a director of the Asian Development Bank. He had a brief stint as ambassador to Russia under Cory Aquino. He died in 2002.

As for Goldberger, no document has been found showing his continued involvement in the rocket program beyond the mid-1970s. A US Department of State cable, dated October 18, 1974 states that he was the chairman of the board and president of a Metro Manila-based firm called Advanced Technological Products, Inc., which specialized in building and fabricating “amphibian cars” and the distribution, importation, and installation of generators. The cable lists his address as Los Angeles, California. Goldberger later permanently relocated to Hawaii, where he became involved in local alternative energy development projects from the late 1980s onward. He died in 2012.

Numerous declassified United States Department of State cables show attempts by the Philippines to acquire complete missile systems from the US after 1975. According to a July 1976 cable, Enrile sent a letter to Marcos regarding a five-year AFP modernization program, which includes a wish list of defense materiel, including US-manufactured Nike Hercules and Chaparral missile systems, both with “support equipment, follow-on spares, tooling and training package.”

A January 1978 cable shows that the US did not want to give the Philippines access to weapons like the Harpoon ship-to-ship missile “on policy grounds.” In October 1979, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Richard Holbrooke took a meeting with Enrile and Marcos, discussing the Harpoon. Holbrooke and Deputy Assistant Secretary Michael Armacoast tried to dissuade them from pursuing the system, explaining how prohibitively expensive it was (a later cable stated that the system cost USD 50 million). Marcos noted that their neighbors—Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan—had their own missile systems; the US diplomats insisted that the Philippines did not need one. Marcos and Enrile stated that they were also interested in the Israeli-made Gabriel system (the same one that Marcos was not so keen on in 1971), possibly buying it from Singapore, effectively saying they were bent on acquiring a missile system even without US assistance—not that the Philippines could afford one.

All these exchanges indicate that the Philippines did not have a functional missile system in the late 1970s, and that they tried—and failed—to acquire missile systems from abroad.

An Associated Press photograph published in the December 23, 1981 issue of the South China Morning Post is captioned “Marcos checks Bongbong…”; the full description states that the photo showed Marcos inspecting “models of Philippine-made 180-mm rockets named after his son” during Armed Forces Day, December 21. Thus, it appears that facsimiles of the rockets were trotted out during parades even in the 1980s, even if there were no more publicized tests or launches—or likely, any form of rocket research.

Project Sta. Barbara shifts from rocket to alcogas

In fact, by then, Project Sta. Barbara had shifted (back) to focusing on alternative energy sources. Between 1978 and 1982, multiple patents were granted to Commodore Protacio and other Sta. Barbara members—such as future Department of Information and Communications Technology undersecretary Eliseo Rio—related to alternative energy development, including one for a solar drier and a handful for alcogas-related methods and devices. In his 1979 State of the Nation Address, Marcos mentioned Sta. Barbara’s “alco-tipid” fuel research. An article written by Protacio, published in a 1981 issue of the Philippine Engineering Journal, states that Sta. Barbara’s alko-tipid research started in April 1979. The March 23-March 28, 1981 “Official Week in Review” mentions a charcoal-fed “hydro-gas” jeepney developed by Commodore Protacio, which was never mass produced. Sta. Barbara was also involved in a USAID-funded windmill dispersal program from 1980 to 1983.

None of the known Project Sta. Barbara patents are directly related to rocket or missile development or any other kind of weaponry. None involved fuel cells or hydrazine either.

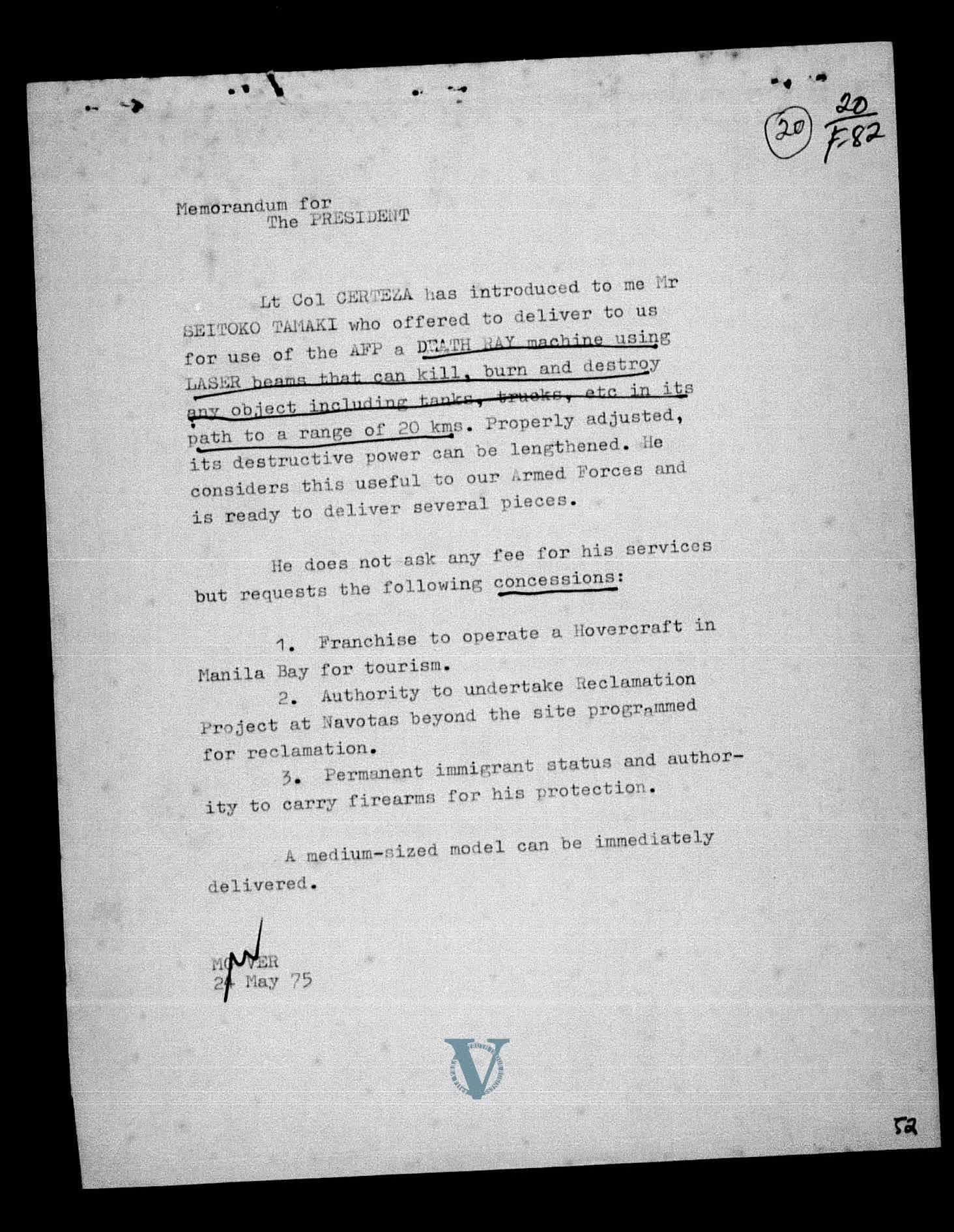

A coda on Marcosian superweapon development: several months before the last publicized Bongbong tests, on May 24, 1975, MGen. Fabian Ver, then head of the Presidential Security Command, sent a short memorandum to Marcos. He said that a Lt. Col. Certeza (likely Rene Certeza, also of the PSC) introduced him to a certain Seitoko Tamaki, who “offered to deliver to us for use of the AFP a DEATH RAY machine using LASER beams that can kill, burn and destroy any object including tanks, trucks etc in its path to a range of 20 kms.” Marcos attached the memorandum to his May 27, 1975 diary entry, where he said, “I have ordered the matter [the “laser-beam weapon”] to be seriously considered.” Between weather control rockets and death rays, and later on deep-sea deuterium deposits, one wonders whether Marcos Sr. was basing his plans for Philippine development partly on science fiction.

The exact date that Project Sta. Barbara was shut down remains unknown. It is safe to say however that government-funded rocket or missile research did not die because of the 1986 EDSA Revolution or because Cory Aquino either abandoned it or shut it down. It died well before that. Marcos does not mention the need to revive the rocket program in his known post-presidency writings.

The Manila Standard reported in July 1990 that thirty-five 500-liter drums of anhydrous hydrazine were hidden “in an underground bunker at Sangley Point airbase in Cavite,” which had “deteriorated to the point that they are in danger of exploding.” The report noted that they were used in “the late President Marcos’ unsuccessful attempt in the 1970s to develop home-grown battlefield rocket capability.” If Sta. Barbara stopped experimenting with hydrazine in the late 1970s, then the drums in Cavite had been lying idle for over a decade at that time.

The dream for the Bongbong rockets ended neither with a whimper or a bang. That’s what the Philippine Marines today call “successful” and “triumphant.”