The June 17 incident in Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal in the South China Sea (SCS) has raised for many sectors in the Philippines the urgency of clarity in U.S. position in the region: does the U.S. have an obligation to defend the Philippines in the SCS under their 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT)?

In the latest Ayungin incident, two Philippine Navy Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats (RHIBs) moored beside the beached BRP Sierra Madre at the shoal in a resupply mission figured in an altercation with Chinese Coastguard (CCG) personnel on speedboats. Machete-wielding CCG personnel allegedly boarded the Philippine navy RHIBs, physically attacked the Filipino navy men operating them, and then towed away two of the boats. One Filipino serviceman lost a thumb in the melee. The boats were later recovered by the Philippine Navy, their rubber sides punctured and navigational dashboard heavily damaged. Philippine officials later claimed that the CCG had seized rifles and equipment belonging to the Philippine Navy.

The immediate question was whether the CCG actions already constituted an “armed attack” as to engage the MDT (for now, it does not, is the Philippine position, and we agree). But the bigger issue, to begin with, is whether the shoal, along with all SCS maritime features and territories claimed by the Philippines, are in fact under the scope of the MDT.

Indeed, it is a matter of religion among ordinary Filipinos that American troops will die with Filipino troops defending Philippine claims to the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea (SCS). Even Filipino scholars profess this view. The Philippine government believes in the “solid commitment of the United States [U.S.]” to defend Philippine sovereignty in the Spratly Islands through “interoperability” between their forces in countering China. It has allowed in Philippine territory prepositioned U.S. military equipment and personnel under an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.

Ambiguity by Design

Yet, the recent statements of the U.S. government on the matter are ambiguous. “[A]ny attack on Philippine aircraft, vessels, or Armed Forces in the South China Sea would invoke our mutual defense treaty,” U.S. President Joe Biden said during the first U.S.-Japan-Philippines Trilateral Summit on April 11, 2024. This confirms the statement of U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken that Americans “stand[s] by our ironclad defense commitments, including under the Mutual Defense Treaty … [which] extends to armed attacks on the Filipino armed forces, public vessels, aircraft – including those of its coast guard – anywhere in the South China Sea.” U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin “reiterated that the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty extends to both countries’ armed forces, public vessels, and aircraft — including those of its Coast Guard — anywhere in the Pacific, including the South China Sea.”

The scope of the territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea are clarified in the 2016 SCS Arbitration between the Philippines and China. According to the Arbitral Tribunal, the Spratly Islands consists of low tide elevations not susceptible to appropriation as territory and high-tide elevations that are not islands but rocks and entitled only to a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea (TS). China, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam claim these rocks, but none of them may regard those rocks as an offshore archipelago.

Taiwan, Vietnam, and Malaysia are American allies, although not at the level of mutual defense that the Philippines enjoys with the U.S. In 1975, upon the advice of the U.S. but “over strong objection of [Filipino] navy and marines,” the Philippines “[withdrew] from … Likas (West York)” to give way to Vietnamese forces, whose presence the U.S. saw as preferable to the “boot-shaking prospect of having to face PRC alone at some future date over Spratlys.” U.S. maintained inaction despite the Philippines raising alarm over Chinese construction on Mischief Reef and occupation of Scarborough Shoal. Recently, while the Philippine military y simulated with the U.S. military in the recapture of an island in the SCS, the U.S. funneled massive military assistance to Taiwan, an opposing claimant.

Thus, the question arises as to whether U.S.’ “ironclad commitment … [under] the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty” applies in an armed conflict involving the Philippines against China and other claimants in the SCS.

1974-1975 U.S. Legal Interpretation of the MDT

Under Article V, the MDT covers 1) an external armed attack on a “metropolitan territory or an island territory in the Pacific” under the jurisdiction of either party; and 2) an armed attack on the “armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific” of either party.

The applicability of the MDT to the Spratly Islands was raised by the Philippines as early as 1975 following Vietnam’s seizure of certain features. The discussion that follows is based on documents in the U.S. National Archives that have been declassified and accessible at https://aad.archives.gov/aad/.

In the document called Ref MANILA 5355 dated April 1975, the U.S. Embassy in Manila sought advice from the U.S. State Department on how to respond to the inquiry of the Philippines regarding the “problem if their [Spratly] island garrisons are attacked” by Vietnam. In the document called Ref STATE 116037 dated May 1975, the U.S. State Department responded that the Philippine government is aware of the U.S. position that the “Mutual Defense Treaty provisions do not apply to Spratlys.”

The U.S. Embassy in Manila further inquired in Ref MANILA 6840 dated May 1975 on the U.S. legal position in a scenario where a “Philippine naval vessel, on high seas, attempting to reach Spratleys for purpose extracting Philippine garrison comes under attack or threat of attack from Vietnamese naval vessels and seeks U.S. naval and air protection.”

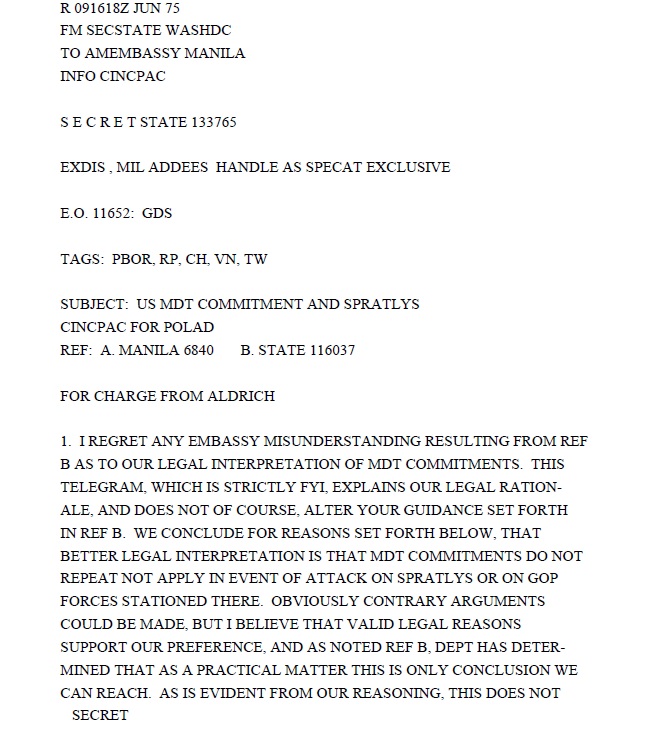

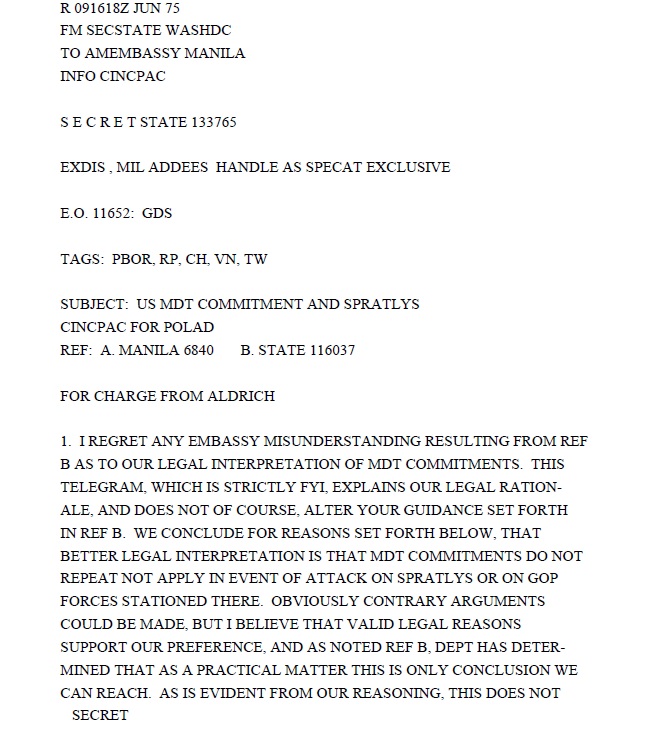

The U.S. State Department issued its “legal interpretation of MDT commitments” in Ref STATE 133765 dated June 1975 and signed by then U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. In this document, the U.S. declared that its commitments “do not repeat do not apply in event of attack on Spratlys or attack on GOP [Government of the Philippine] forces stationed there.” It cited two grounds: first, the Spratly Islands are not part of Philippine territory; and second, the Philippines is not a claimant in respect of the Spratly Islands. The discussion that follows quotes directly from Ref STATE 133765.

According to the U.S., it has “not recognized GOP sovereignty” over the Spratly Islands. During the MDT negotiation and ratification in 1952, in its [U.S.] mind the “Spratly Islands all fall outside Philippine territory as ceded to U.S. by 1898 Treaty with Spain;” this is why “U.S.G. [U.S. Government] maps accompanying presentation of MDT also exclude Spratlys from territories covered by MDT.”

The foregoing US interpretation not only of the MDT but also of the 1898 Treaty of Paris (and by extension the 1900 Treaty of Washington and 1930 Treaty of Washington) is binding on the Philippines as the U.S. (not the Philippines as a colony) was the main party to these treaties. The recent contrary interpretation of Justice (ret.) Antonio Carpio and of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines on the import of these treaties to the Spratlys dispute would merely be wishful thinking.

Moreover, the U.S. designated the 1951 negotiations on the Japanese Peace Treaty as the critical date for the purpose of identifying the claimants to the Spratly Islands.

[Under international law, the critical date is the point of crystallization of territorial claims such that any claim raised beyond that date is deemed barred. In the famous Island of Palmas Case, the U.S. lost to the Netherlands because its attempts to exercise sovereignty over the disputed island were barred by the critical date. For this reason, the critical date is immovable insofar as it determines which states are real claimants.]

Going back to the U.S. legal interpretation of the MDT, it declared that “at time of negotiation of 1951 Japanese Peace Treaty,” specifically the provision on the status of the Spratly islands, only China and Vietnam interposed claims. In the following year 1952, “at the time the MDT [was] signed, [Philippines] had asserted no claim to any of the Spratly Islands and had protested neither Vietnamese nor Chinese claims.” Thus, even as the U.S. did not favor any of the claimants to the Spratly Islands, it did not consider the Philippines as one of them.

While declaring that the MDT does not apply to the Spratly Islands or to Philippine forces on the Spratly Islands, the U.S. clarified that “this does not portend any legal attempt to deny application of the treaty to … Philippine forces if attacked in situation described para 3 Ref A [MANILA 6840],” in which a Philippine naval force is attacked on the high seas in the SCS (i.e., the Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) under the 1982 UNCLOS).

In sum, the U.S. denies any legal obligation to defend the Philippines in the event of an armed attack on the Spratly Islands or on Philippine forces there on the grounds that Spratly Islands were not part of the territory that it acquired from Spain and passed on to the Philippines, and that the Philippines is not among the claimants to Spratly Islands. However, it acknowledges a legal obligation to defend Philippine military forces, vessels and aircrafts, and coast guard vessels in the event of an armed attack while they are situated on undisputed Philippine EEZ in the SCS.

1979 U.S. Legal Interpretation of the MDT

In 1978, the Philippines formally claimed the Spratly Islands as an offshore archipelago on the ground that “while other states have laid claims to some of these areas, their claims have lapsed by abandonment and cannot prevail over that of the Philippines on legal, historical, and equitable grounds.” Still, then-U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance did not declare the MDT applicable to the disputed Spratly Islands. Rather, Document 578 of American Foreign Policy Basic Documents 1977-1980 is a 1979 letter to then-Philippine Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlos Romulo, in which Vance reiterated the U.S. legal interpretation of the MDT.

Vance declared that armed attack under the MDT refers to external armed aggression against any part of Philippine metropolitan territory as defined by the 1898 Treaty of Paris between Spain and the U.S. and the 1900 Treaty of Washington between Great Britain and the U.S. (amended in 1930), as well as island territories in the Pacific that are under Philippine jurisdiction. Moreover, “armed attack on any Philippine armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific would not have to occur within the Philippine metropolitan territory or island territory under its jurisdiction in the Pacific in order to come within the definition of Pacific Area in Article V.” Thus, armed attack on said forces or vessels taking place in undisputed maritime areas in the South China Sea would fall within the scope of the MDT.

The 2024 U.S. statements have not revised the 1975 and 1979 legal interpretation of the MDT— consistent with US state practice for nearly half a century. The 2024 statements are even careful to limit U.S. commitment in the SCS to situations of armed attack against Philippine “armed forces, public vessels, aircraft-including those of its coast guard” but not on the Spratly Islands or Philippine forces therein.

The question is whether U.S. commitment was deemed expanded by reason of the SCS Arbitration.

2017 U.S. Legal Position on the SCS Arbitral Award

Following the issuance of the SCS Arbitral Award, Taiwan deployed a naval armada “to patrol the South China Sea”. Being non-parties to the SCS arbitration, Vietnam and Malaysia are not bound by it but have been selective in their support of the Arbitral Award. For instance, Vietnam supports the Arbitral Award’s ruling that China’s nine-dash line is contrary to UNCLOS. Yet, in its 2023 administrative map, Vietnam maintained its claim to the Spratly Islands as an offshore archipelago or Troung Sa, thereby defying the ruling that no littoral state may claim an archipelago in the SCS. The claim of Malaysia to a CS beyond 200 nm from its coast ignores the Arbitral Award that in the area of the Spratly Islands only the Philippines has an EEZ/CS and, by extrapolation, an extension of the CS (2016 Arbitral Award, paras. 635-642, pp. 257-259).

The U.S. interpreted the Arbitral Award to mean that China “cannot lawfully assert a maritime claim … vis-a-vis the Philippines in areas that the Tribunal found to be in the Philippines’ EEZ or on its continental shelf.” China “has no lawful territorial or maritime claim to Mischief Reef or Second Thomas Shoal, both of which fall fully under the Philippines’ sovereign rights and jurisdiction, nor does Beijing have any territorial or maritime claims generated from these features.”

It should be borne in mind that the Philippine EEZ and Continental Shelf (CS) is interrupted by numerous rocks with pockets of TS. The SCS Arbitral Award recognized that there are rocks within 200 nautical miles from the Philippines coasts that are occupied by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Malaysia and that each rock, including Itu Aba occupied by Taiwan, has a 12-nautical mile TS. As the Arbitral Tribunal had no jurisdiction to resolve the territorial status of these pockets of TS vis-à-vis the maritime entitlement of the Philippines, it merely declared in para. 683 that the Philippine EEZ and CS is “beyond 12 M from any high-tide feature within the South China Sea.”

Thus, an armed attack by China against the Philippines would engage the U.S. commitment under the MDT if directed at Philippine armed forces, public vessels, and aircrafts, including coastguard vessels, while the latter are within the Philippine EEZ but not on the disputed Spratly Islands or their respective TS. However, the question remains whether a similar armed attack by Taiwan, Vietnam, or Malaysia would also engage U.S. commitment. Through their new coast guard laws, China, Taiwan and Vietnam authorize use of lethal force against perceived threats to their territorial and maritime claims in the SCS.

The Second Thomas Shoal where the Philippine Navy’s 80-year-old BRP Sierra Madre has been intentionally beached is a low tide elevation found in the Philippines EEZ. Nevertheless, BRP Sierra Madre, though derelict, is a Philippine naval vessel and the troops stationed therein are covered by the MDT. Philippine coastguard vessels and personnel on rotation and resupply missions in Second Thomas Shoal have been harassed and attacked by China by means of vessel-ramming and firing of laser beams and water cannons. These drew U.S. condemnation but not military force in defense of the Philippines.

Near Reed Bank, the Philippines converted decommissioned oil and gas platforms into naval outposts. Philippine forces and vessels in these installations would come within the coverage of the MDT, especially as Reed Bank is recognized by the U.S. as part of Philippine CS.

Another hotspot between the Philippines and China is Scarborough Shoal. China presently controls access to this shoal. The Arbitral Award recognized that fishing in the territorial waters of the shoal is a right common to Filipino, Chinese and Vietnamese fishermen. Consequently, any fishing dispute between the Philippines and China in the shoal would be territorial in nature. The 1975 U.S. legal interpretation excludes such dispute from the scope of American obligation to defend the Philippines. The U.S. interpretation of the Arbitral Award did not revise this legal interpretation of the MDT.

A Nothing-Burger

As if by design, the Kissinger memo – followed by the Vance letter and current U.S. pronouncements – had created a fine ambiguity concerning the scope of obligations under the MDT. This ambiguity is one liable to enthusiastic (mis)interpretations by Filipino leaders, much to American advantage and quite possibly, to deep Filipino sorrows.

American obligation to defend the Philippines in the South China Sea is a nothing-burger. The question for Filipinos is whether they would risk upgrading this obligation under a renegotiated MDT given the certainty of a conflict between U.S. and China for dominance in the region. The question for Americans is whether they would be willing to foot the bill with their lives on tiny rocks thousands of miles across the Pacific.

Postscript: US-Philippines MDT Bilateral Defense Guidelines

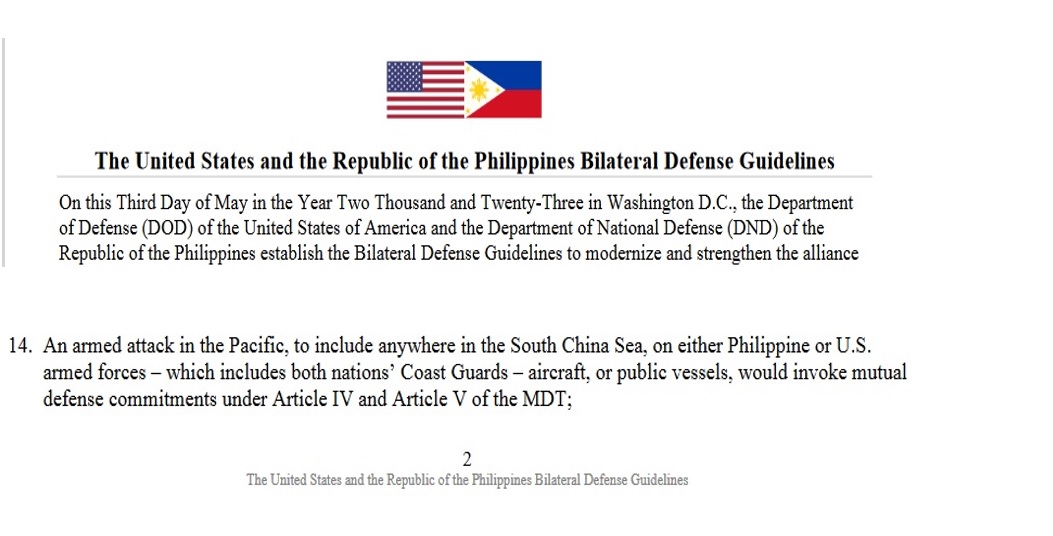

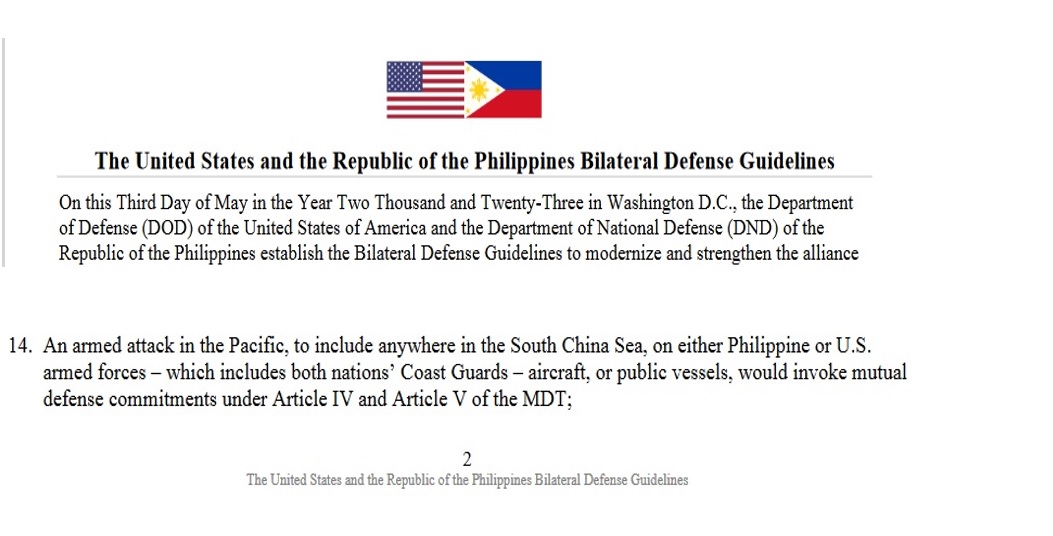

As an earlier and much shorter version of this article was being considered for publication, the US and the Philippines published a new set of guidelines governing existing bilateral defense agreements founded on the MDT. The relevant paragraphs of the 3 May 2024 guidelines are as follows:

- An armed attack in the Pacific, to include anywhere in the South China Sea, on either Philippine or U.S. armed forces – which includes both nations’ Coast Guards – aircraft, or public vessels, would invoke mutual defense commitments under Article IV and Article V of the MDT;

- Both sides recognize that threats may arise in several domains—including land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace – and intend to work closely through a variety of initiatives and consultative mechanisms to build cooperation and interoperability in both conventional and non-conventional domains;

- The United States and the Philippines reaffirm the importance of the 2016 Arbitral Award on the South China Sea;

Whether or not the guidelines are binding under international law and Philippine law, the language they used hardly changes the standing US commitment under the MDT. If anything, the apparent ambiguity by design is continued by the guidelines.

While they provide that any armed attack covered by the MDT now includes those committed “anywhere in the SCS”, such an armed attack has to be on either Philippine or U.S. armed forces – which includes both nations’ Coast Guards – aircraft, or public vessels (para. 14).”

The guidelines do not make any reference to disputed territories, including those occupied by the Philippines. They do not expressly state that the U.S. recognizes Philippine sovereignty on occupied SCS features adjudicated as “juridical rocks” or high tide elevations by the 2016 Arbitral Award, such that Filipino forces stationed on them, if attacked, will draw U.S. armed support.

If at all, as we have already argued, following the 2016 Arbitral Award, the scope of the MDT now embraces U.S. and Philippine armed forces operating in maritime areas in the SCS that the Arbitral Award had declared as part of the Philippine EEZ.

This is confirmed by para. 16, which reaffirms “the importance of the 2016 Arbitral Award on the South China Sea.”

In other words, the official U.S. stance on the MDT’s coverage in the SCS has moved a wee bit: not quite embracing Philippine-occupied or claimed territories (juridical rocks or HTEs) in the area but now including the EEZ adjudged by the UNCLOS Tribunal as belonging to the Philippines. And that is saying a lot.

Still, the guidelines stop short of expressing unequivocal endorsement of Philippine territorial claims in the SCS.

Our interpretation of the new guidelines is echoed by a May 29 opinion piece published by Rand Corporation Senior Defense analyst Derek Grossman with Foreign Policy. In that essay, Grossman argues that it is now time for the American government to take “an official position on the disputed territories within the South China Sea” because it has not yet done so.

After all, as he notes, in 2012, the Obama administration recognized the Senkaku Islands as belonging to Japan, not China, in their East China Sea standoff, declaring that any attack on the islands would trigger Article 5 of the U.S.-Japan security treaty. “Manila,” he writes, “would obviously appreciate a similar clarification, which would signal to Beijing that Washington now considers attacks on the Philippines’ recognized EEZ to be direct assaults on its sovereignty and territorial integrity, which are already covered by the treaty.”

In fact, Grossman may have overlooked important points of international law differentiating Senkaku and Spratly Islands. For one, Senkaku is subject of a 1972 Reversion Treaty under which U.S. recognized that Japan retained sovereignty over the rock even after the Second World War and declared China’s belated claim in 1970 as already barred by the critical date, i.e. the 1951 Japanese Peace Treaty.

Nonetheless, in view of the SCS Arbitral Award proscribing claims to the Spratly Islands as an offshore archipelago, the scope of application of the MDT is broadened to cover armed attacks on Philippine “armed forces, public vessels, aircraft-including those of its coast guard” taking place on low-tide elevations that are beyond the pockets of TS of rocks but situated within the Philippine EEZ in the SCS such as Ayungin Shoal.

At the very least, an express U.S. commitment to this effect would signal, if not mutual defense, then mutual respect.

Is the U.S. stance on the SCS sustainable? We don’t think so. As shown by the recent Ayungin incident. the dynamic in the SCS dispute between the Philippines and China is towards further escalation. The American pronouncements on its so-called “iron-clad” commitments will be stretched by the current circumstances beyond their original intention.

In the end, American reticence towards Philippine territorial claims will be exposed for what such commitment really is: a nothing-burger.

(A shorter version of this piece was first published as a two-part post in the Asian Journal of International Law Voices blog on 17 and 20 May 2024.The authors are independent scholars of international law based in Copenhagen and Manila, respectively.)