“Many processes of personal and social liberation were characterized, in part, by behaviours of transgression and disobedience to a dominant political and religious order. The behaviours of women, considered by some as harmful to the religious social order, become signs of the affirmation of justice for many of them. Transgressing and disobeying unfair orders are actions that strengthen and respect life.”

Yvonne Gebara, Brazilian feminist theologian

Telling the story of Sudan inevitably begins by approaching it from the women who have inhabited it, from a feminist and African perspective without a doubt. This view is intended to contribute to Sudan’s recognition debts as an African country beyond the generally assumed Arab view. It must start from recognizing that the country has socio- cultural and physical-geographical characteristics similar to the countries that make up the so-called “Horn of Africa”.

Showing the struggles of Sudanese women necessarily leads to revealing a historical perspective that goes back to the time of slavery and colonialism. In this report, I will take current events as a starting point, that is, the revolution that the country has experienced in 2018, and then establish connections with the more and less recent past. For this, there are key questions that I intend to serve as a guide: why did the revolution come about? Why did women lead the revolutionary process, what rights and what symbols do they claim? And how to face the challenges of Sudan and its women?

The 8 months of revolution in Sudan -from December 2018 to August 2019- marked a milestone for the country’s history and especially for the history of the most oppressed, Sudanese women. And this affirmation is anchored in the history of the country and of them specifically, it is there why they took to the streets and led the revolutionary process.

The Turkish period (1820-1885), for example, rooted the slave religious theme and established concubinage. It is at the time when slavery was established with weight and the arrival of the English took this as a basis. The British colonization in Sudan did one thing they know how to do very well, apply the divide and conquer formula. When they arrived, they did not consider that the South existed, nor that the people from the south who lived in the north were citizens, they colonized the Arabs, but they did not know those who lived in the south. The English did not do much to abolish slavery, contrary to what was happening at that time in the world and by the church. In Sudan, they played a lot with this, they started to free the slaves when they realized that it was more profitable to have the slaves free because of the agricultural projects that existed in the country. Along with the theme of slavery was the theme of mutilations; even though in Sudan the British were the ones who made the laws, they did not make a lot to put an end to this issue and although there was some specific resistance such as the case of a

British general who mutilated his daughters went to jail, there were demonstrations against it; the feminist bet was to raise awareness of mothers and not go to jail. Therefore, the necessary articulation between change of structure, change of mentality, education and legality was not achieved. The English did not touch these issues, they were only interested in the looting of the country in material terms, which also means that it had a cultural and symbolic cost, just for not addressing specific cultural issues. An example of this is found in reference to the issue of “the concubine” and “the mother of the son.” The Qur’an allows that the Arab Sudanese man who has one is entitled to 4 wives and on top of that he can have a concubine. The concubine doesn’t count, but when a child is born to her, they sometimes take her as their wife and that causes her to change status. In this the British did not interfere, and they did not free many slave women because they considered that this entered into private and religious life. They released more men because they needed them for agriculture. And although women participated in the majority in agriculture, according to the sexual division of labour, their work did not count. The slave had housework and agricultural work, which was considered a continuation of the same work.

The 1960s and 1980s corresponded to a regime led by the late Jaafar Numeiri, who called himself euphemistically socialist but was actually a military dictatorship. This regime could be recognized as open when compared to the 30 years of the Islamists, but there was no such openness. What the leader of this regime promoted favored the women of his party, the socialist. In other words, while an opening is recognized, it is “lame” because women who were not from the socialist party were in the same condition. At this time there were negotiations in which other African countries intervened to try to reach a peace agreement between the north and the south. However, the clauses of the peace agreement always benefited the north, for example, the oil wells are in the south and the north wanted to benefit without giving anything in return. The political group of Doctor John Garang, who was the leader of the revolutionaries of South Sudan who was assassinated by the Bashir government, advocated for women to leave the house and for there to be equality and to distribute political and economic power, but unfortunately that it went nowhere.

At this time socially, there were no changes either. It did not change the mentality regarding discrimination and the idea that “that is the black from the south”; The word Hadem, which means slave or black, was used a lot, many times as a joke, but the difference in colour or skin tones, rural or urban origin, etc., always remained.

In this war of identities, the people who live in the South have been joined by non-Arab communities (even though they are Muslim) from the North-South border, such as the Nuba from the South of Kordofan and the Ingassana from the South of the Blue Nile. This clearly makes that war not a mere resistance to the imposition of Islam, but an ethnic struggle against the domination of some people who claim to be, ethnically and culturally, Arabs and superior to black Africans with whom they do not Feel identified. Although we Sudanese people have a lot of Arab culture, we are in an area where we are neither Arab nor African… the Arabs look at us with great contempt and the Africans are angry with us and do not recognize us. In this geographical distribution, among other factors, is the origin of the Sudanese conflict.

Until the country broke up, people from southern Sudan of slave origin, and specifically women, engaged in domestic service, prostitution or the sale of alcoholic beverages. The latter, perhaps from the Western perspective, is not interesting, but many women are dedicated to this sale of alcoholic beverages. On the grounds that Northmen are drinkers, though the law forbids them to drink; therefore, these women dedicate themselves to making homemade drinks earning a pittance. In some cases, they have a small bar in the house and everything in a condition of absolute illegality. In these circumstances they are exposed to being raped and physically mistreated.

Returning to the history of the country, it should be noted that during the 30 years of the Bashir dictatorship, the female group was among the most affected by the shari’a (the laws that govern Islamic societies, based on the holy book, the Koran.) public order laws that prevented women from working in the streets. They had already been beaten, imprisoned, flogged and murdered by the state. So, this is one of the reasons why they took to the streets during the revolution period; Their objective was to protect the revolutionary process, because they knew it meant a real change in their lives, they wanted to see their dream of a new and egalitarian society come true.

In summary, as can be seen, after the British era, various governments arrived, all with a cut of dictatorships. None resolved two issues of a political and cultural nature: ethnic and gender. On the one hand, religion got in the way and meant a setback on those issues; on the other, the intellectuals at the time did not bother to address them either, although at present it is the subject of analysis for them. On the subject of mutilations, there has not been an important mixed movement that stopped the matter either, because it has only been for women.

That is why, between December 2018 and August 2019, women took to the streets and held protests as an organized and vanguard group; representing between 60 and 70 percent of the protesters. The reasons are clear and as I pointed out before, their lives in the last three decades were marked by prohibitive and oppressive laws that subjected them. It was religious fundamentalism and the National Islamic Front (Sudan Muslim Brotherhood) that supported Bashir’s coup in 1989, responsible for the imposition of Islamic law. Since then Sudanese women, girls too have been enduring a Sudanese version of the harshest extremist application and interpretation of Islam.

These laws even defined what women could wear and what was forbidden to them. Unusually, issues such as child marriage (giving the father the right to marry off his daughter at age 10) and marital rape were allowed; instead women were not allowed to wear pants in public. They also regulate how they must cover their hair and even how they travel in public.

In the months of the revolution, the government brutally attacked the protesting women and, being these majorities, therefore, let us assume that there were not a few who were abused. Rape and sexual violence became their strategic practices, rather weapons of war. A senior military officer told the officers: “Break the girls, because if you break the girls, you break the men.”

This state of affairs constituted the fuel for women in Sudan to raise their voices against the military state and against cultural restrictions, also reproduced within families that played along with a traditional society reinforced by conservative discourse and behaviour. of the State.

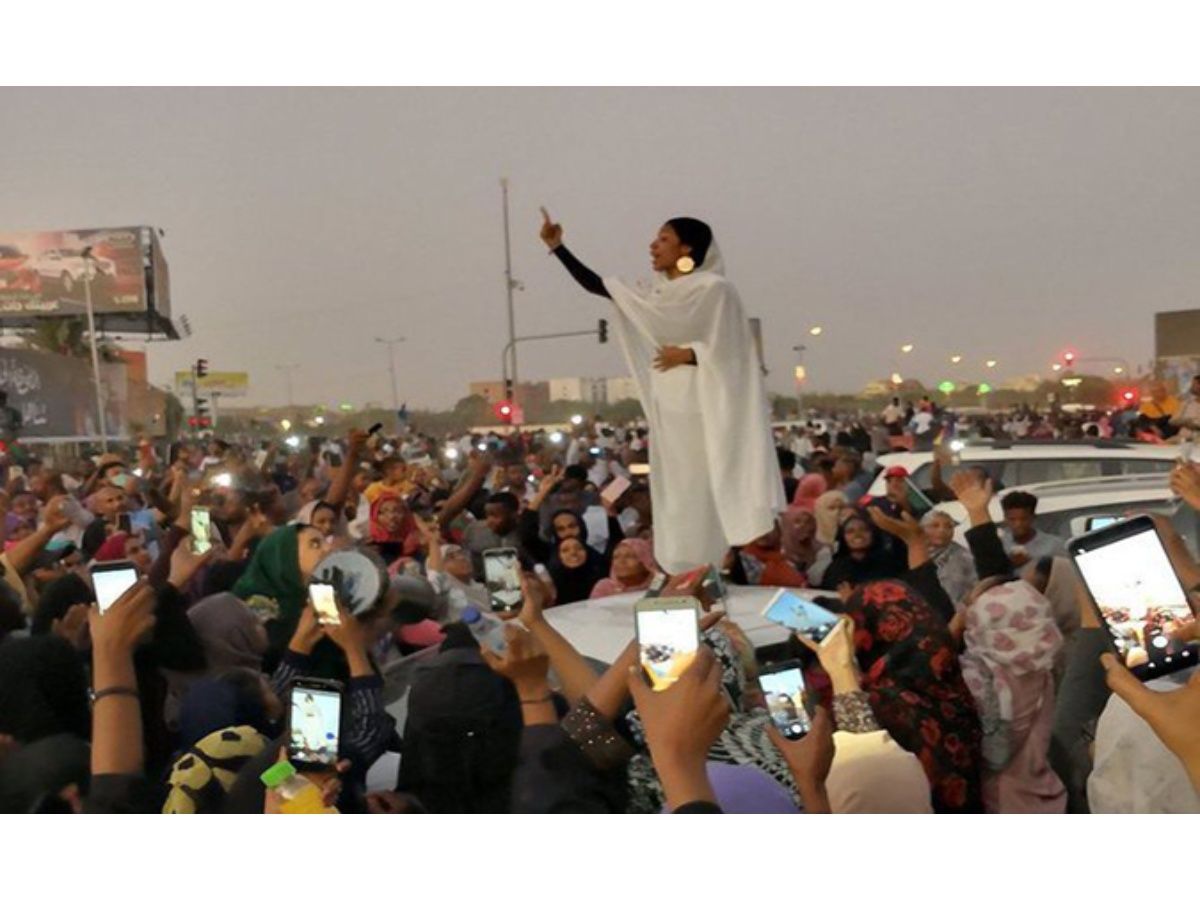

The revolution led by women put the cultural and generational issue on a par with the political, in short, the identity issue. A symbol toured the world, Alaa Salah, a 22-year- old (identified by BuzzFeed and some Arabic-language media outlets.) engineering and architecture student standing on top of a car raising her right arm as she addressed the crowd in a chant, “Thowra!” the crowd shouted, which means, “revolution”. And the symbol was on her thobe, a cotton smock, traditionally worn by professional Sudanese women in the workforce; also, the fedaya (gold earrings in a circular shape typical of Sudanese women and that every woman passes on to her daughters.) that she wore symbolized the transfer from woman to woman, from generation to generation; and why not thirst for justice in general that the women of this town carry.

Although it could lend itself to controversial interpretations in addition to the thobe and the fedaya, the title of Kandaka or “queen” was attributed to this girl, which could be seen as the idealization of the Sudanese woman and her concept of femininity. However, I prefer to assume it as I have mentioned, as an emblem of historical pride, of rescuing the place of women in the country’s history, of the warriors who were always present and at the forefront of the independence struggles, of obtaining and respecting their rights. individual rights. It became a symbol sealing the ethnic differences that could be interpreted and focusing on the political struggle of women in revolution.

With all this historical legacy, the Sudanese revolution will have to face various challenges, which are mostly linked to the female issue and its articulation with the country’s political and social spheres.