“Fisherfolks are all for development, but they hope such development would not sideline them and only benefit a few. Why not develop and nurture the fishing industry instead?”

By MAVIC CONDE

Bulatlat.com

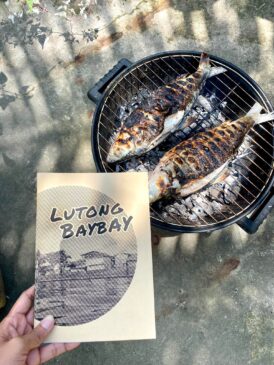

DUMAGUETE CITY — How do you cook inun-unan?

In a clay pot, simply add vinegar to fish sprinkled with salt and top with ginger.

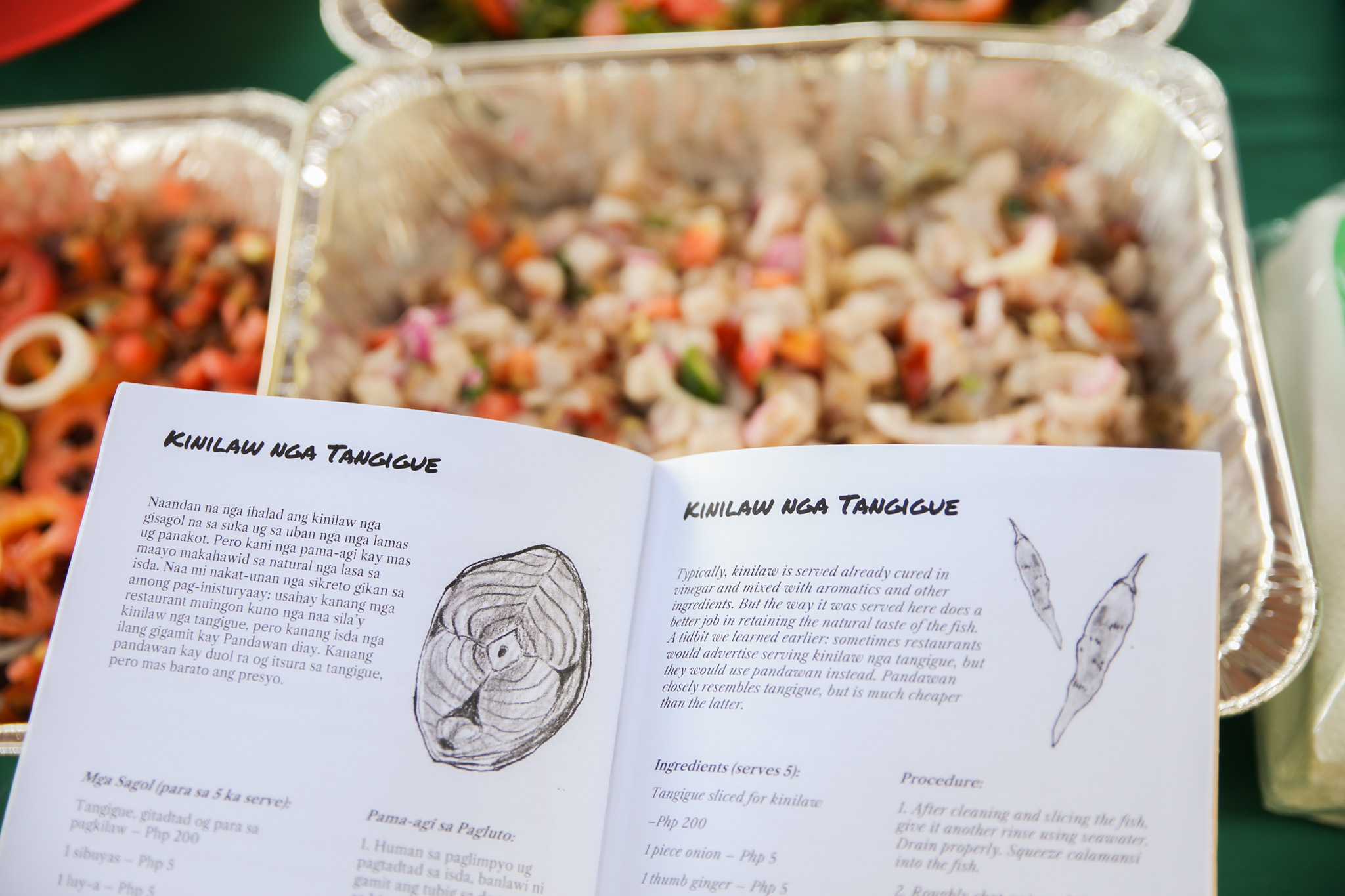

Inun-unan is the Visayas region’s version of paksiw (fish simmered in vinegar), according to “Lutong Baybay”, a cookbook zine that serves as a response of women in fishing communities to the now-deferred mega-reclamation project in this biologically and geographically important coastal city.

Although the project has been shelved, locals remain vigilant on the possible renewal of the massive project and for ongoing ones.

“I took part in creating this zine because I want other people to become aware of our situation here, and how important the sea is to us,” a community leader who asked to be called Nanay Bona told Bulatlat over the phone.

“[Lutong Baybay] shares the narratives and collective stories of local women echoing the need for the essential ecosystem of their communities and the seas: for their survival as much as its conservation,” Kabataan Para Sa Karapatan – Negros Oriental wrote in a Facebook post.

Asserting these basic rights means “[amplifying] the generational struggle of fisherfolk for [redacted] access to food, of secure livelihood, of sustainability and development for all,” the group added.

Following strong opposition from various sectors, the city government halted approval for the P23-billion “Smart City” reclamation project, in which buildings will rise for a mix-use residential and commercial hub.

With an area of 174 hectares, the damage caused by the reclamation will be irreversible and will extend far beyond its coasts, where equally rich marine ecosystems, such as Apo Island, can be found.

Converting natural ecosystems for a dump and fill project means sacrificing natural shoreline protection and carbon sequestration provided by thriving mangrove trees, seagrass beds, and coral reefs. Simply put, it would mean a missed coastal resource management opportunity for climate mitigation.

The Dumaguete coastal women’s call for solidarity with fishing communities also serves as a call to action on climate change. As an archipelagic country in a rapidly warming world, their struggles are also ours.

Through this zine, the women, particularly mothers, join the work of building solidarity within and beyond their coastal communities to protect their seawater through something that connects us all: food.

Escabeche, torta

For barangay Tinago where Nanay Bona lives, the zine zoomed in on escabeche nga mamsa (sweet and sour trevally fish) and tortang tugnos (anchovy omelet). Mamsa is served in the resorts for sinigang often at a premium price.

“These food features show that even if we are poor, we get to eat these for viands,” Nanay Bona said. Her neighbors also look for her escabeche, but her children’s favorite is the escabecheng galungong (round scad), if not fried.

She said if the pantawan (boulevard) wasn’t built, they would also have crabs, shells, sea urchins, and seaweeds for food. It was built for shoreline protection but, according to her, it worsened the flooding.

The zine describes barangay Tinago as flood-prone due to its location – “right after the mouth of the river from the shoreline.” So, “[f]looding is expected every year, and floodwater level can vary from ankle to shoulder-deep.”

The boulevard was recently widened.

Tinolang isda, inun-unan

Photo by Bea Banzuela

Aloja, from barangay Looc where the pier is located, claimed that the fish catches now are no longer the same as they used to be.

“The noise from the pier and the expansion of the boulevard seemed to have driven the fish further away,” she explained over the phone.

She also expressed disappointment that the boulevard is now off-limits to fisherfolk and locals (for swimming) because it is used for government events and tourism.

The Looc marine sanctuary, according to Aloja, could have been affected by the boulevard extension if their village chief had approved it. The first Marine Protected Area in Dumaguete, established in Banilad 20 years ago, now promotes connectivity by sustaining fish stocks and supporting neighboring fisheries. It also led to a change in behavior, as locals used to oppose the idea and are now fighting to keep it.

The recently released Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report is crucial for charting paths for long-term climate actions. The final warning in the report to keep global average temperatures within 1.5°C is determined by how quickly we put those into action, particularly the “substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use.”

According to the report, “[p]rojected carbon emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructure without additional abatement would exceed the remaining carbon budget.”

Even nature-based solutions are only effective “under the lowest levels of warming,” Lourdes Tibig, advisor to the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities and lead author in the IPCC Special Report on Oceans and Cryosphere, said in a past webinar.

For Nanay Bona and Aloja, whose children’s families all live in the same house, continued sea warming means increased exposure to coastal flooding due to sea level rise and food and livelihood scarcities due to acidification. Not to mention that, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration(NASA), “90 percent of global warming [occurs] in the ocean.”

“We’re a family of 14, including my seven grandchildren, and we all prefer fish to meat,” Aloja said. At the time of the interview, she was serving tinolang isda (fish ginger/lemongrass stew) and inun-unan, which she claims is a favorite of her neighbors among the dishes she sells.

According to the zine, Looc residents could easily return home with a bucket full of fresh scallops after a quick swim or dive.

Aloja works as a waste collector for their barangay Materials Recovery System (MRS) and earns P1,800 (USD 33.12) a month. “Our chief village understands how little our monthly wage is, so our barangay office no longer asks for share from the sold recyclables and waste collection fee of P30 (USD 0.55) pesos for each household per month,” Aloja said.

Her husband is a porter, while Nanay Bona’s is a driver. The latter said she doesn’t want her children to fish for a living because it is hard, but she wants them to learn to protect the environment.

“This is a legacy I want them to have,” Nanay Bona said.

That sentiment is echoed in the zine by the following statements: “Fisherfolks are all for development, but they hope such development would not sideline them and only benefit a few. Why not develop and nurture the fishing industry instead?”

Dumaguete’s 1,000 small-scale fisherfolk provide protein sources to the 38,000 local consumers through their seafood catches. Add to that the gleaners, resellers, and women who work in fish processing, as well as those who turned to the sea for food and job during the pandemic. Through the inextricable link between food and the sea, the zine hopes to foster solidarity.

Nanay Bona continues to advocate, despite being the only voice in the Women’s Group 2, a newly formed group for Tinago women. “What matters is that they heard my opinions,” she said.

If offered a relocation site with a source of income, she said it depends, but she was certain of one thing: “It’s so hard to start over.” (JJE, RTS, RVO)