By MONG PALATINO

Bulatlat.com

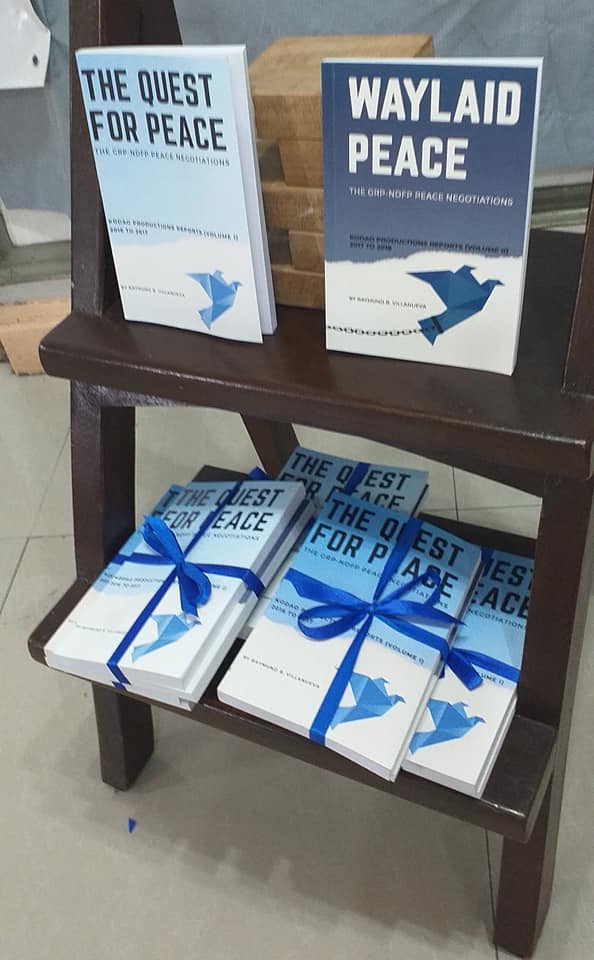

Review of ‘The Quest for Peace: The GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations’ by Raymund B. Villanueva

Rodrigo Duterte promised peace and federalism but he ended his term without achieving both. He unilaterally scuttled the peace negotiations with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and abandoned the idea of turning the Philippines into a federal state.

There were high hopes of negotiating a political settlement with the CPP after the elections in 2016 but this quickly vanished in less than a year as Duterte unleashed his all-out war policy against the communist movement.

The book chronicles the revival of the peace process at the start of the Duterte administration, the four rounds of talks, the aborted fifth round, and the abrupt collapse of the negotiations even if the panelists and mediators expressed their willingness to go further to deliver a successful final peace agreement.

Both mainstream and independent media covered the talks but the latter sustained the news coverage especially during the period when the formal talks were suspended. News reports often relied on what the parties of both sides of the conflict wanted to share with little space for the perspectives of observers and other stakeholders of the peace constituency. Thus, the importance of getting news and information that educates the public about the prospect of the peace process, the particular agenda of each round of talks, and the necessary interventions of concerned citizens who had been vigilantly observing the negotiations.

The news articles in this book written by the current chairperson of Altermidya and published by independent multimedia platform Kodao provide readers with comprehensive insight about the talks.

The author has direct access to negotiators which proved useful in validating reports amid the spread of disinformation and even state-sponsored fabrication during the negotiations.

There are limitations to what a news format can convey but this also makes the book a valuable reference for scholars and peace advocates. An archive of stories that can guide researchers in fact-checking the claims of both the Duterte government and the National Democratic Front (NDF). The book is a printed Wikipedia of the peace process during the first year of the Duterte administration.

It is common to read reports parroting the point of view of Duterte propagandists about the alleged insincerity of the NDF without even attempting to offer balanced coverage.

But Raymund Villanueva’s dispatches are fair. His grasp of the history of the peace process is reflected in the reports that highlight the key points of landmark peace agreements. He quotes government negotiators and the peace spoilers in the Duterte Cabinet, but he also makes sure readers are provided with a proper context and rejoinder from the NDF side.

Soon, the terminated peace process will be reduced to a simplified narrative offered by both parties and their supporters.

We need books like this that can temper our biases and allow us to better understand the process that started with “guarded optimism” but ended with the government resuming its scorched earth policy against the CPP and NDF.

The book will remind us that Duterte released several peace consultants and that the Joint Monitoring Committee for the implementation of the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law was convened, but at one point he has gone “berserk” with his barest minimum condition for the signing of a bilateral ceasefire. The CPP called Duterte a “double-speaking thug” which is quite an accurate description for the unremorseful authoritarian leader.

NDF leaders were accused of being dogmatic and devious but they extended goodwill gestures such as hinting support for the proposed federalism and the adoption of Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER) to fulfill the development aims contained in the government’s Ambisyon 2040 program.

The NDF identified not just the continuing incarceration of activists but also the brutal “tokhang” (the bloody campaign against the illegal drugs) as a stumbling block in the continuation of the peace process.

Despite these challenges, negotiators found ingenious ways to keep the process alive. Norway’s diplomats praised negotiators for being “solution-oriented”. Indeed, the demand for a bilateral ceasefire was not ignored since it was linked to the signing of Comprehensive Agreement on Socio-Economic Right (CASER). Negotiations for CASER also moved forward as both parties have agreed to support free land distribution and irrigation.

But these gains did not matter to Duterte and the hawks in his Cabinet who only wanted the capitulation of the CPP and NDF. They would also not appreciate the migrants who met the negotiators in Rome, the religious delegation who prayed for the success of the talks, and the peace assemblies attended by tens of thousands across the country. These voices did not matter to Duterte who later imposed Martial Law in Mindanao.

The book quotes a Catholic nun who reminded both parties that those who are most affected by social inequalities should have the strongest voice in the negotiations. It is an appeal worth remembering as we consider the possibility of resuming the peace process under the government of Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

Villanueva, who is also a poet, captured the sense of desperation among those who yearned for peace with these words. “Dawn has broken here, but the sun, hidden behind a gloomy sky, has yet to make its presence felt.” ![]()