By JC Gotinga

I was a broadcasting student at UP Diliman, and Journalism 101 was part of the syllabus. But I had no plans of becoming a journalist, and I didn’t really concern myself with current affairs.

I thought I was going to be a hotshot TV-and-film director. This was before there were smartphones. We shot our projects with MiniDV handycams. The iPod, a music player that didn’t require CDs or tapes, was just a rumor.

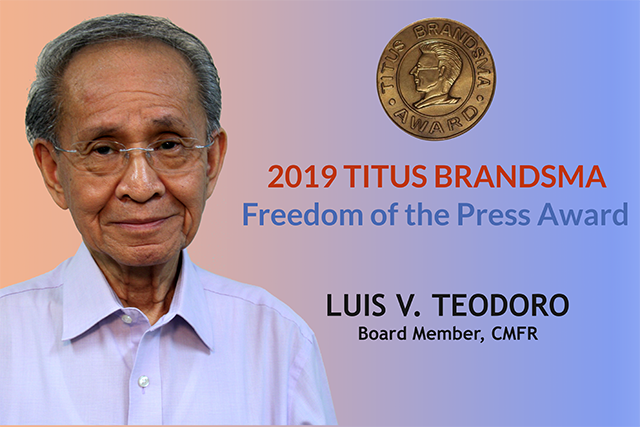

I remember next to nothing from my Journ 101 classes. What I do remember in vivid detail was the time I made Professor Teodoro so fuming mad, I worried he was going to have a heart attack.

My friend Naomi and I sat on the back row of his class – very telling of how much interest we had in the subject. That day, a new issue of a university paper that was a parody of The Collegian was going around. In the middle of class, Naomi nudged me and showed me something funny – inappropriate – on the back page. I don’t remember what it was, but I blurted out in laughter.

It was a scene out of a jackass movie where the whole class turns to look at you, tutting their disapproval.

I had never offended a teacher before that. I was a teacher’s pet all through elementary and high school, and I’d generally been cool with my college profs. It’s just that journ class bored me to death, and I didn’t think I’d have anything to do with journalism.

Even I was in shock and disbelief at the creature I had, at that moment, become.

“Who laughed?” Professor Teodoro demanded to know.

I raised my hand.

I forget what he had been discussing, but it was, like all of his lectures, serious. In so many words, he told me how dare I laugh in the face of such profundities. How dare I make light of a subject, of a practice, of a tradition for which he and his contemporaries had been incarcerated and tortured, even murdered.

He was so angry he was trembling. I half-expected him to faint. His eyes behind his thick glasses watered.

He walked away from the whiteboard and towards the window. He held on to the sill, and I thought he was being dramatic. The light from outside cut him a sharp profile from where I sat.

He then started talking about the mortal dangers he and his contemporaries lived through while fighting the Marcos dictatorship. He mentioned Amando Doronila who I gathered was his friend and an equally battle-scarred journo.

I think back on this now and I realize it might not have been anger that riled him up but frustration. Frustration at how, no matter how sharp, eloquent, beautiful, profound his lectures were, the message was still lost on the likes of me – heathen children of a younger generation privileged to not have known mortal crisis.

The heat of his rage dissipated and his tone mellowed. Still by the window where the light outlined his sharp nose and tall forehead, he talked about the struggles of the era we were lucky to have missed. He talked about jail. I couldn’t imagine him, the most dignified man I had ever met, a prisoner.

I imagined myself as a prisoner. I asked my self, fleetingly, if I would ever let myself be so given to a cause like patriotism or free speech that I’d end up a prisoner.

No, thanks, Professor. Thank you for your sacrifices. But I am a soft child of my fortunate generation. I am sorry you lived through a terrible time, but now is a different time. A more enlightened time. People and the world have evolved, and we don’t need to inherit your hard-skinned virtues.

My thoughts at the time. And then life and current events happened. Here I am, a journalist.

I understand now how events can turn so that a good, dignified man can end up in prison. That powerful people with much to lose are capable of torture and other nasty things because, like every other person, they’re selfish, but the stakes for them are much higher, and they’d probably long sold their soul to get to that level of wealth and influence anyway.

I’ve now seen for myself the [many forms of] oppression the Professor battled. I now try to battle them myself as another wielder of a pen. I now ride the nag I inherited from him and his contemporaries to confront dragons disguised as windmills. I, like him, now even make references to literary classics.

Time has a way of teaching you the lessons you missed when they were first taught to you, right? I’ve found myself staring out of windows a few times, wondering what went wrong and what I could have done differently and how else I could communicate what I think people need to understand. In the few years since our democracy started to decline, I’ve been in a constant rage, wanting to both embrace and destroy this heathen generation that can’t seem to recognize its own good.

I don’t think Professor Teodoro would have remembered me. I did hope to find myself again in the same room as him and introduce myself as that student who laughed during his class two decades ago, and say that I am sorry. Not just for disrespecting him, but for taking his message for granted.

That message found another way to reach me, and I still cannot really claim to be his student in the real sense of the word. But at least I think he would have enjoyed the irony and savored the poetic justice time has served him.

I could wish his heart wasn’t broken by our country’s recent history, but I am certain it was. I, the heathen who only recently came to the light, am heartbroken. How could he, who had wagered far more for the cause than anyone, not be?

His sun set under the rule of the same family that terrorized his generation. If we are headed for darker times, then his passing is a mercy to one who has fought battles long enough.

Because what I did pick up as the man averted his gaze from me that day I disrespected him was that he would never, ever, have stopped fighting. Even then, he seemed frail of body, but I saw his spirit, and it made me tremble. Only his body could fail him.

Rest in peace, Professor Teodoro. Please forgive me. #