MAGGIE WILSON has brought national attention to the country’s information disorder once again, a problem so prevalent since the 2016 presidential election that it has become normalized to Filipinos.

Weaponized disinformation is part of public consciousness, as popularized in local shows like Dirty Linen and Senior High, yet our awareness of the issue hasn’t translated to solutions more than seven years down the line.

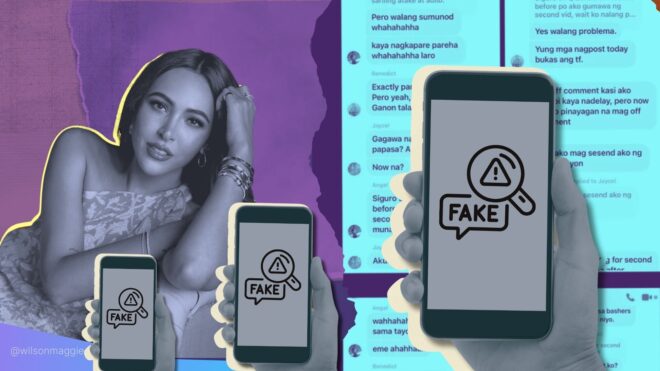

Wilson’s trending Instagram story series exposed exactly how a paid fake news troll network was able to systematically execute its disinformation campaign against her partner, her business, and herself.

How fake news proliferates in the Philippines isn’t exactly news. The entire disinformation ecosystem was already explored by journalists, through investigative reports, and by academics, through published research.

For example, the methods involved in the smear campaign against Wilson were not unlike those detailed in the 2018 study “Architects of Networked Disinformation: Behind the Scenes of Troll Accounts and Fake News Production in the Philippines.”

So how did Wilson manage to cause a buzz so disruptive that it has at least triggered serious discourse among journalist circles?

What the media industry can learn

Before any newsroom can say they have updates about disinformation and always have, consider your work’s actual impact, rather than intention. Because for sure, the specific public relations entities involved in disinformation campaigns are already taking note from the Wilson mishap.

Speaking of Wilson, what she managed to achieve with her IG story exposé was notable, but neither scalable nor sustainable for disinformation victims and journalists.

Her initiative’s strength was its style and form. She uploaded social media “receipts” and noted that she didn’t even reveal everything she had on hand yet. Heavy on graphics and light on text, Wilson communicated her message visually by packaging everything she wanted to say in an accessible yet memorable format.

Wilson technically did not reveal anything new about how the media industry already understands our local disinformation networks. However, what was groundbreaking was how she finally visualized the fake newsmaking process from beginning to end.

All the people and processes mentioned, albeit anonymously, in previous research were given a human face. If existing investigative reports and academic research proved to be too complicated of a read for the public, nothing could be more clearer than Wilson’s stories on Instagram, a platform used by around 19 million Filipinos.

We have already heard about the scripts, the group chats, the production, down to the payment and marketing. If you couldn’t imagine it before, you could see it in front of you now thanks to Wilson.

She also name-dropped PR entities responsible for the fake news, particularly those behind her smear campaign. You can’t beat a system without taking down the people behind it.

To be fair, researchers can’t do the same thing because the condition of getting information from confirmed perpetrators of disinformation is anonymity. Journalists also have to worry about our outdated and overpowered libel laws and countless ethical concerns. If you’ve seen the 2015 Oscar Best Picture “Spotlight,” the Boston Globe’s investigative team could’ve published an impactful report midway through but decided not to because that would mean letting all the bigger fish get away.

Without discrediting Wilson’s best practice in visual communication, she was able to accomplish this partly due to her background. She is a wealthy society member who has the legal right to sue all these trolls who unwittingly defamed her. Other victims probably aren’t as brave because they lack the money and the means to defend themselves, whereas Wilson doesn’t need to know everything when she can simply hire a legal team.

Also if it’s not clear, she was able to obtain all the information from her influential attackers lest they face impending legal action. Journalists, by virtue of the laws and ethics governing the media profession, cannot threaten anyone for information.

What the PR industry will learn

Just like 2016, 2019, and 2022, the media will be slow to act in the aftermath of Wilson’s latest headlines. Reactive and not proactive.

This whole disinformation debacle only showed a fraction of the publicly available social media posts where PR entities openly hired trolls to spread fake news about the likes of presidential candidate-turned-head of state Ferdinand “Bongbong Marcos Jr. The fake newsmakers were sloppy with their electronic trails out in the open all this time, yet it took Wilson, not the media, to expose these.

If there’s anything we’ve learned about PR executives and officers, it’s that they work fast.

At most, Wilson can sue some or all of her trolls. These content creators might cry foul that they were only reading a script in exchange for P8,000 maximum, but they are as culpable as the criminals they enable.

Since the incident became viral, the likes of Sassa Gurl have even called on content creators to be more judicious with their work by researching the topics they discuss. Influencers, big and small, will be temporarily scared to take on fake news jobs.

Meanwhile, the PR bosses will learn from this mess, clean up their sloppy trails, and improve their chaotic processes. Chances to get exposed like this again will be less and fewer. And for what?

Regardless of who’s behind the disinformation campaign against Wilson, the motivations appear to be personal and/or professional, not necessarily political.

Sure, it’s a slap in the face for the so-called architects of networked disinformation. But more so, it’s a missed opportunity: a slip on the wrist for all the local politicians whose ties to these fake news networks could have been exposed. That will be infinitely more difficult after they adapt to this otherwise inconsequential drama.

What we should all learn

Like it or not, political disinformation’s ground zero is the Philippines, being used against opposition members in and out of elections. It’s time we end the problem where it started.

Disinformation victims and journalists must work together. There are lessons, as well as points for improvement, to unpack from Wilson’s Instagram stories.

Like her, victims are entitled to confront the trolls to track the disinformation down the trail it originates from. The press can likewise employ visual journalism by making use of graphic special executions on both news websites and their social media accounts.

That’s only the start, but the point is to gather qualified visual evidence before releasing anything explosive — which only succeeds in alerting PR executives to learn from their mistakes with minimal consequences to their operations. Collect and verify as much information as needed, then go for the jugular. Don’t give them any time to react.

After this Wilson saga, the shadier members of the PR industry will have protocols for every situation. If ground-level fake news operators are confronted by the likes of her or anyone else, they can immediately deactivate their account. Deleting posts is only counterproductive, because it’s impractical to delete everything without removing their other work or risk leaving other incriminating information.

Or they can be made to sign a non-disclosure agreement. That way, they can be sued by higher level disinformation officers if they reveal anything to anyone. They don’t even have to be furnished a copy to avoid leaving a paper trail while still giving them the idea that they will be sued if they “snitch.” Troll hiring can even be done face-to-face to eliminate the electronic trail altogether.

What’s the point of this hypothetical exercise? In order to beat the enemy, you have to think like them.

All the fake newsmakers think about is how they can better reach the people, which they seem to be doing a better job at than the media, if we’re basing from all the commonplace chaos in the Philippines resulting from the information disorder.

Popular culture like the Philippines’ Dirty Linen and Senior High, or even South Korea’s Queenmaker, are the public’s closest link to understanding this disinformation ecosystem, because it’s visual and relatable. If their representation of fake news lacks nuance, that’s only because existing literature doesn’t have images and names to help visualize the disinformation scene.

What these shows do get right is the principle. It’s not intuitive and it’s not enough to just practice self-defense then learn to all live together peacefully. We have to act on the perpetrators, because all our efforts to combat theirs will be wasted.

What will a fact check achieve if fake news spreads so much faster? While still necessary, it’s not enough. We need to go beyond and end their operations by doing our best work, like investigative journalism that’s so bulletproof, it can name-drop names the public needs to know.

Maybe cross-newsroom collaborations, or even partnerships with civil society groups? More effective, more urgent, more inclusive. More.

We can learn from the likes of fan-favorite protagonists like Hwang Do-hee and Alexa Salvacion, who beat disinformation by focusing squarely on the people behind it. They didn’t succeed by documenting the platform that gave rise to the antagonists, but by destroying that very platform. Once that solid foundation of disinformation is removed, the Carl Yoons and Carlos Fieros of the world will all fall down.

For now, the ball’s in our court.

Maggie Wilson’s IG story exposé is a lesson for everyone, but the real test is who will act first.